No more Mr Nice Guy: does Sunak really have what it takes to fight dirty?

‘Reasonable Rishi’ seems to have morphed into ‘Small Boats and Single Sex Spaces Sunak’. His apparent lurch to the right on migration and culture wars has got Andrew Grice thinking: who is the Real Rishi?

When Nigel Lawson died in April, Rishi Sunak was quick to recall that when he, Sunak, became chancellor, one of his first acts was to hang a picture of his Thatcher-era predecessor above his desk.

Sunak did not remind us that he also chose portraits of Labour’s Hugh Gaitskell and William Gladstone, the four-time Liberal prime minister. While he admired Gaitskell’s scepticism about European integration and Gladstone’s fiscal conservatism, his decision to display politicians from three different parties was revealing: Sunak knows his own mind but sometimes keeps the rest of us guessing about his true instincts.

His public image is as “Reasonable Rishi”, the polite internationalist equally at home in California and London, a workaholic technocrat happier poring over a spreadsheet than making a tub-thumping speech. He is also “Rich Rishi”, though opinion polls suggest that while his family’s wealth doesn’t really concern voters, they worry he is “out of touch” and cannot relate to their struggles in the cost of living crisis. He compounded his problem with silly stunts like filling up someone else’s car and not knowing how to use contactless payment.

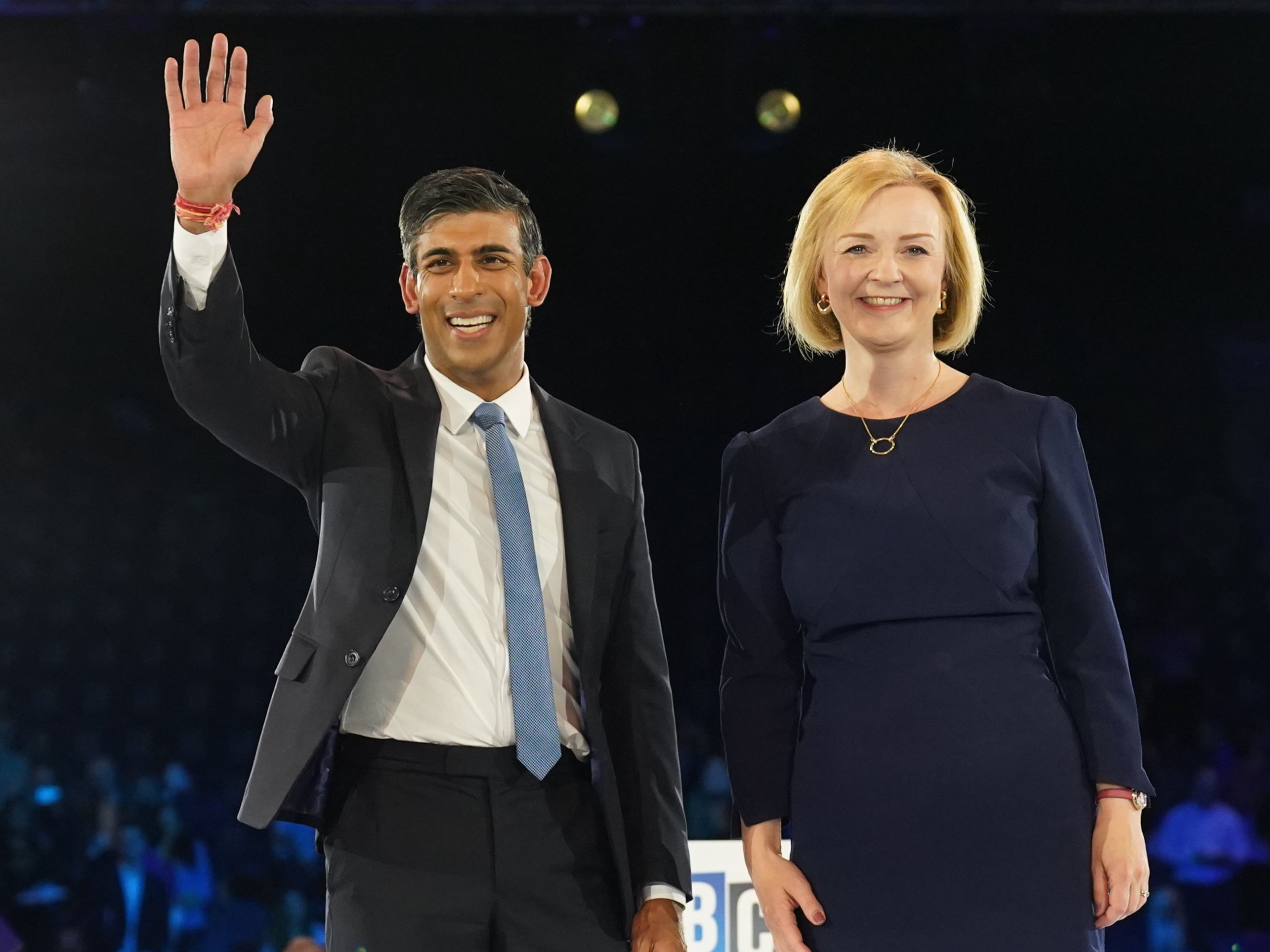

What matters most is: who is the “real Rishi”, politically? Until recently, he was seen as a centrist who brought competence after the amateur hour Liz Truss show. Delivering stability after chaos reinforced the sense that Sunak was a moderate clearing up the mess of a reckless right-wing libertarian. Although he backed Brexit in 2016, Sunak was more pragmatic about implementing it than Boris Johnson or Truss and has rightly rebuilt the EU bridges they burnt. In his early days as prime minister, he appealed to Remainers in the Tories’ blue wall in the south more than he did to Leavers in the red wall. Tory strategists hoped he could successfully woo both, that his personal ratings would level up those of a party that suffered terrible brand damage under its two previous leaders. But the opposite happened. “The party dragged him down,” one Tory insider told me.

His strategy wasn’t working and, with Labour enjoying a 20-point poll lead, a rethink was inevitable this autumn. It began early: the Tories’ unexpected victory in the Uxbridge and South Ruislip by-election was the launchpad for more aggressive attacks on Labour, led by Sunak personally, as he mapped out dividing lines between the two main parties – on green issues, migration and trans rights, with more to come on crime and “woke capitalism” – aimed at putting Labour on the wrong side of public opinion. So Sunak is no more Mr Nice Guy. Speaking about the small boats, he declared: “The Labour Party, a subset of lawyers, criminal gangs – they’re all on the same side, propping up a system of exploitation that profits from getting people to the UK illegally.”

His tweet got a reaction and was designed to – in order to magnify his message. It wasn’t a one-off; his allies were delighted with the response to this opening shot in what will be a long, dirty election campaign. The PM whose mantra was once a “culture of enterprise” to boost growth now wages a “culture war”. Sunak’s tweet was part of this wider canvas. Ministers defended Lee Anderson, the outspoken Tory deputy chair, for saying migrants who did not want to live on the Bibby Stockholm barge should “f*** off back to France”.

While his change of tack pleased right-wing Tories clamouring for a “real conservative” government, it appalled One Nation Tories who fear Sunak’s appeal to the party’s core vote will revive its “nasty party” image and repel under-fifties and liberal Conservatives. As one former cabinet minister put it: “The risk is that his strategy appeals to one section of the party’s support but alienates the rest. There are plenty of people who like the idea of a centre-right party – including a lot of ‘don’t knows’ who haven’t moved to Labour – but they dislike this populist tone.”

One Nation Tories, less vocal than their noisy right-wing counterparts, will warn Sunak not to vacate the centre ground where elections are won. One senior backbencher said: “There is a real risk that in trying to prop up the core vote, he falls between two stools and ends up pleasing no one.”

There are also doubts in Tory land whether Sunak is the right man to front such a campaign. “It’s just not him,” one Tory adviser told me. “It’s true that he is much more right wing than Boris but he is not an attack dog. What he is good at and enjoys most is immersing himself in the detail as he did on the Windsor framework [on the Northern Ireland protocol] and finding a solution to an intractable problem. We should play to his strengths.”

There’s a danger voters will be confused by the contradictions between the “new Rishi” and the bright youngish technocrat they thought they knew, and might view the increasingly strident attacks on Labour as evidence the Tories cannot defend their record in 13 years in power.

Some One Nation Tory MPs still hope the old Sunak – the pragmatic problem solver who can steady the ship in troubled, rapidly changing times – can re-emerge. But that moment has surely passed

Sunak allies insist he is not reinventing himself and they are right. Events framed Sunak as a liberal Tory in the mould of David Cameron. But while he shares Cameron’s fiscal conservatism, which brought austerity after the 2008 financial crisis, he is a social conservative. Cameron took on his party by supporting gay marriage, while Sunak pandered to his by vetoing the Scottish government’s plan for gender self-ID and now plays up the trans issue.

However, Sunak will need to do better than he did in the Tory leadership contest against Truss a year ago, when he complained about “woke nonsense” that “wants to cancel our history, our values – and our women”. His move bombed with his Tory audience, so why would it work with voters?

In the public’s mind, Sunak is still best known for his landmark furlough scheme during the pandemic. He splurged £400bn, saying the crisis was “not a time for ideology and orthodoxy” and he would do “whatever it takes”. That wasn’t strictly true: cabinet colleagues recall how he ruthlessly filleted a £15bn Covid catch-up plan for schools.

It grated with him that he borrowed more in his first 10 months as chancellor than Gordon Brown did in nine years. So did the lockdown measures approved by Johnson; Sunak was on the libertarian side of that argument.

Yet, that was not how it looked when he went to battle with Truss. Knowing where the votes were, she was happy to be seen on Sunak’s right flank. Sunak told Tory members: “My values are Thatcherite. I believe in hard work, family and integrity. I am a Thatcherite, I am running as a Thatcherite and I will govern as a Thatcherite.” The problem was that Truss had already begun her Thatcher tribute act as foreign secretary.

Sunak was correct in arguing his economic stance was more in tune with Thatcher, who repaired the public finances before cutting taxes. His promise to gradually reduce the 20p basic rate of income tax to 16p cut little ice because Truss told Tory members what they wanted to hear, adopting Ronald Reagan’s approach of immediate tax cuts to boost growth.

So the right-of-centre Sunak was cast as the moderate by his opponent. He had the support of liberal and centrist Tory MPs who hoped he was “one of us”, Paradoxically, Remainer MPs liked the Leaver Sunak, while Brexiteers flocked to Truss, a 2016 Remainer.

The clues about the “real Rishi” we are seeing now were there but it suited some Tories to ignore them. To be fair, he never hid them. As a newly elected MP in 2015, before his meteoric rise to chancellor, colleagues described him as a “classic economic and social liberal”. He argued that “in normal times public spending should not exceed 37 per cent of GDP”. (It is currently 46.2 per cent).

In his most detailed statement of his philosophy, his 2022 Mais lecture, he said: “I believe that a system built around the free exchange of goods and services the responsibility of the individual, the division of labour, is the morally right way to organise our economy.” But he did accept there should be limits to the free market.

Will Sunak’s tack to the right work? Although it has ruffled some Labour feathers, Team Starmer is not losing sleep. One senior Labour figure told me: “This is not Sunak and he knows it. He is a serious guy, not a grubby streetfighter. He doesn’t do the gutter convincingly and he won’t be able to sustain it. He needs and wants to demonstrate what a fifth-term Conservative government would be about. By smearing and setting attack dogs on Labour, he just looks as if he is fighting a rearguard action against a party that’s heading for victory.”

Some One Nation Tory MPs still hope the old Sunak – the pragmatic problem solver who can steady the ship in troubled, rapidly changing times – can re-emerge. But that moment has surely passed: Sunak has taken a right fork in the road and there is no turning back. The danger is that it could leave him stranded in no man’s land, unable to appeal in sufficient numbers to voters whose main concerns come the election will be the economy and the NHS, and not single-sex toilets or lefty lawyers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments