Why Eurostar trains built to link Manchester to Paris permanently hit the buffers

Trains were constructed and new track even laid to link cities across the North, Scotland, and Wales to the Channel Tunnel, writes Jon Stone. But the plans fell at the last hurdle

Britain once had big plans for a sprawling network of rail services that would link Scotland, Wales and the north of England directly through the Channel Tunnel to the continent.

It was a striking vision of the future, which came close to becoming reality. Trains were built, sections of tracks constructed, and even timetables planned.

But despite being practically ready to go, the “north of London” Eurostar services never ran – the plan was killed off by a combination of politics and economics.

Just hop on a train

The services north of London were part of the vision for the Channel Tunnel from almost the beginning: the Channel Tunnel Act 1987 required British Rail to draw up a plan to provide “international through services serving various parts of the United Kingdom”.

This is exactly what Britain’s nationalised railway operator did.

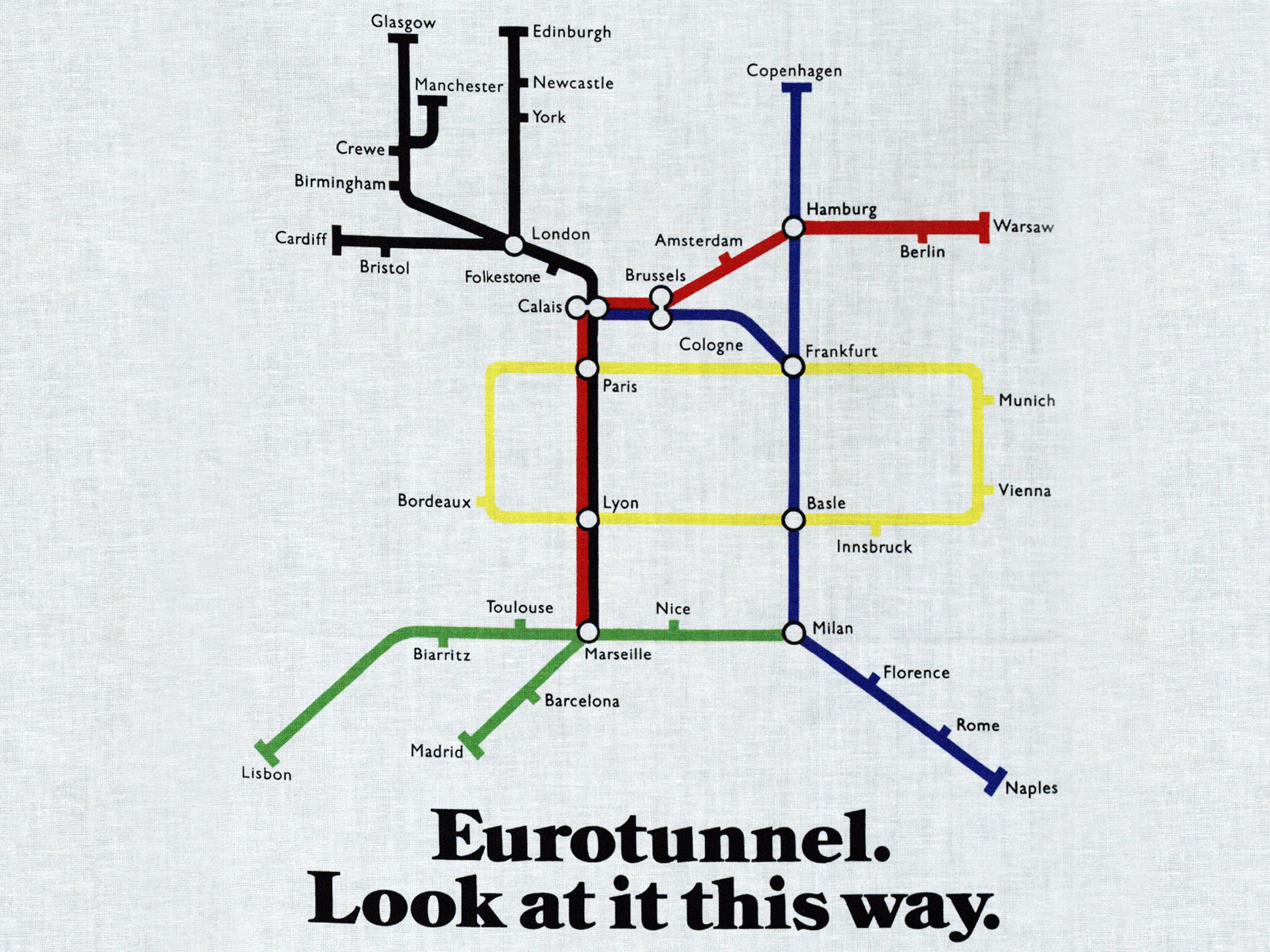

“In 1993, you’ll be able to hop on a train from Birmingham to Brussels. Or catch the 8.23 from Newcastle to Nice (change at Paris),” one magazine advert for Eurotunnel ran.

The services were to be a combination of express day trains and overnight sleepers, running largely on existing railway lines.

During the day, Manchester to Paris would initially have taken 5hrs 45mins; Edinburgh to Brussels 8hrs 15mins; Birmingham to Paris 4hrs 30mins. But the journey times would have been cut by around an hour on completion of the Channel Tunnel rail link in Kent, which opened in 2007.

Overnight “Nightstar” sleeper trains would have begun their journeys in Glasgow, Plymouth and Swansea, picking up passengers in cities along the way and arriving not just in Paris and Brussels, but also in Amsterdam and Frankfurt, in time for breakfast.

Fares were never advertised, but one report to parliament in 1999 suggests that a typical advance return from Birmingham to Paris would have cost £106, slightly less than the air fare at the time.

This was all far from being a daydream: the notable thing about the plans is just how advanced they were.

In 1991, British Rail ordered seven new express trains to operate the services, at a cost of £180m. Crucially, they conformed to Channel Tunnel safety standards and were able to run on the British, French and Belgian networks. They were delivered in 1995-96. It also purchased new sleeper carriages for the Nightstar services.

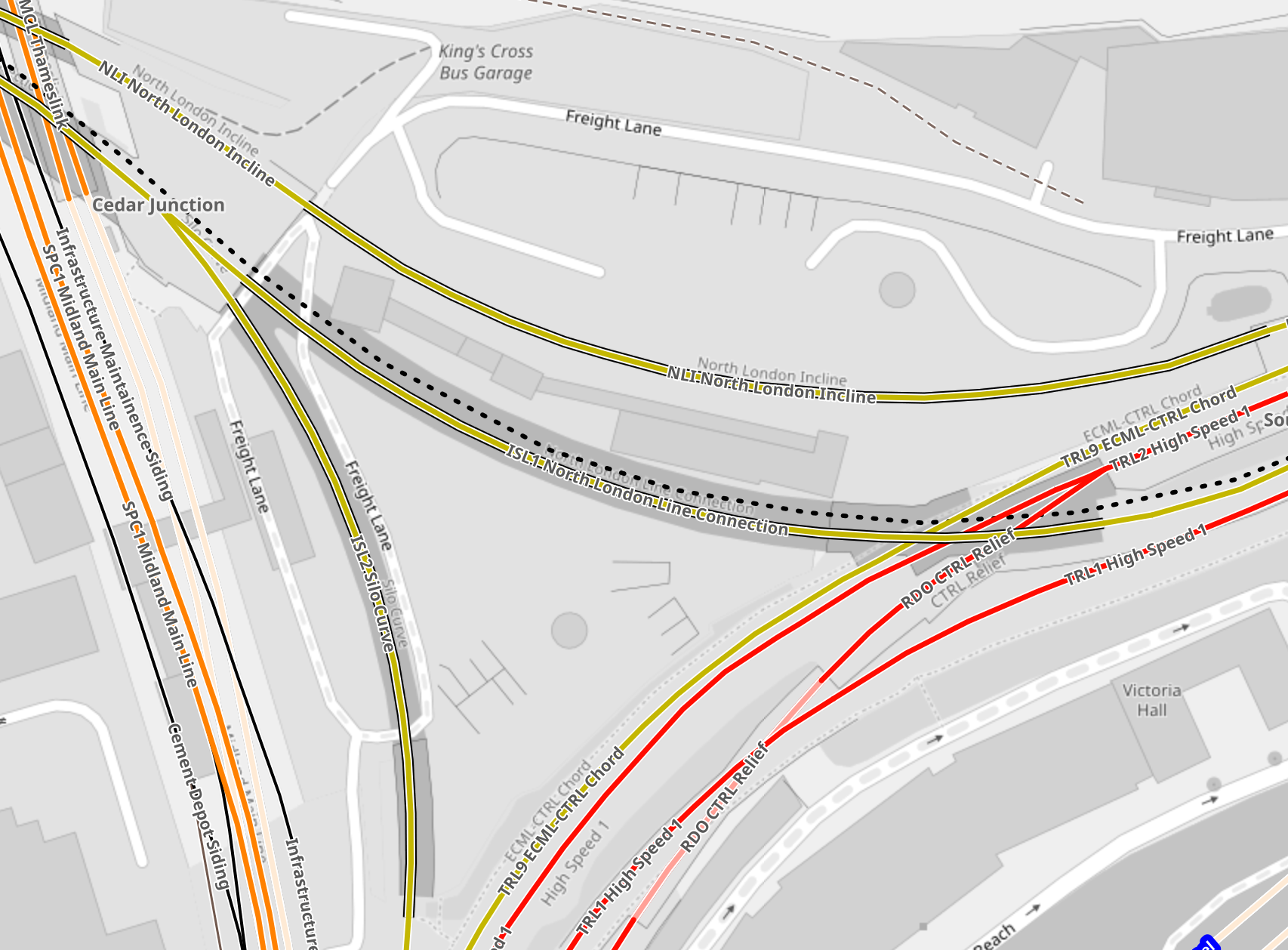

New junctions were constructed around London to allow the trains to get from the North to the tunnel; still there to this day, they are sometimes used by freight. Mostly, the services would have passed along the West London and North London lines – now part of the Overground – to get across London.

A depot was even built at Longsight in Manchester to look after the new rolling stock. Many still remember its large signs, visible from the road, reading: “Le Eurostar habite ici”. In fact, it stood empty and unused for a decade before being repurposed.

Paradise lost

A number of factors conspired to kill the Regional Eurostar services. The same European integration that was supposed to be cemented by the cross-Channel link also brought with it the liberalisation of air travel.

Out of that came low-cost airlines like Ryanair and easyJet, offering bargain flights to destinations across Europe. Suddenly, the relatively slow rail services looked less competitive. Would they be able to attract enough passengers to break even?

Archive documents show British Rail had concerns about the commercial viability of the services from the beginning – but they were a political priority set by act of parliament, to show that the whole country could benefit from the tunnel to Europe.

Yet while cheap flights undermined the project, they were far from the only factor in its demise.

Long-distance international and sleeper trains are still common on the continent despite the existence of low-cost airlines: in practice, some passengers are willing to pay for a more comfortable and environmentally friendly option. Trains also tend to take people right into city centres, cutting out hours of messing around at airports.

But there is a crucial difference between what happens on the continent and the plans for Regional Eurostar: the question of border control.

Since the 1990s, most EU countries have been part of the Schengen area, which abolished passport controls between member states. As a result, passengers getting a train from Hamburg to Prague no more have to show a passport than someone travelling from London to Manchester. But Britain has always remained stubbornly committed to checking passports.

This has bigger consequences for international rail travel than you might imagine. Not only is queueing for passport control inconvenient, but passengers travelling internationally who have been through controls have to be kept separate from domestic passengers.

The rule means that a train running from Manchester to Paris cannot rely on the demand from passengers travelling from Manchester to London to help it break even financially, as a similar international service would on the continent.

The perverse result is that, even though trains from Manchester to London are commercially viable, and trains from London to Paris are commercially viable, a train from Manchester to Paris might not be.

Notes from one 1987 meeting between the French and British Railways managers show frustration that border control formalities between Britain and France were more strict than “at the frontier between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic” – across the iron curtain.

“Every effort must be agreed to cause the habits of the British administration to evolve towards practices which are generalised on the continent,” the meeting resolved.

This problem might have gone away had Britain joined Schengen, as many expected it eventually would – but it never did.

Privatisation

Yet despite these handicaps, Regional Eurostar might still have survived, were it not for the winds of political change.

Since the late 1960s, the government had recognised the concept of the “social railway” – public transport was not there just to make money, but had wider benefits to society.

Regional Eurostar had always been more of a political priority than a commercial one: a product of the idea that giving other parts of the country access to the benefits of the Channel Tunnel was worth doing whether it made money or not. It had been written into an act of parliament, after all.

But when British Rail was privatised, this kind of thinking took a back seat. Politicians expected that the privatisation would create a competitive market, drive new innovation, and pay its own way. They regarded their role as being to get out of the way and let this happen. And the public could certainly not be asked to subsidise services through taxes.

Had the government decided that the services were simply worth paying for, the trains could still have run. But when the Department for Transport was told that subsidy would be needed to run the services in 1999, no money was forthcoming. With British Rail gone and no organisation pushing the project forward, the idea was effectively dead.

Look upon my works, ye mighty

The advanced state of the project when it was abandoned means that you can still find remnants of it today – sometimes in places you might not expect.

There are, of course, unused rail junctions outside St Pancras station, meant to connect the north of London services to the Channel Tunnel rail link. Today, they only see the occasional freight service.

But most notably, the trains built to run the Regional Eurostar routes have ended up in an eclectic mix of places.

In the early Noughties, some of the high-speed sets were leased by GNER, the former East Coast operator, to run on domestic routes between London and York. While a number were repainted in GNER colours, a few were left in the original Eurostar livery (with the logos removed), occasionally confusing or delighting passengers.

Later, some of the seven units were repainted into French state railway SNCF’s colours, sent across the Channel, and drafted in to run domestic high speed TGV services in northern France. More recently, a few ran low-cost services to Belgium.

Yet perhaps most intriguing is the fate of the Birmingham-built sleeper carriages intended to be used on the Nightstar services. These have found their way to Canada, where they have been plying the long route from Montreal to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

As well as sleeping cars built for the ill-fated Eurostar services, Canadian passengers have been enjoying 20 lounge cars in which British passengers might have sipped champagne on their way to the French Riviera.

The depot built in Manchester to look after the trains lay empty for around a decade until 2005, when it was intermittently brought back into use for other rail operators. It has most recently been used by Northern Trains to house its new regional fleet.

Time for a comeback?

International rail travel is undergoing a resurgence on the continent, with more high-speed lines opening and sleeper services being reinstated.

But barring major changes, it’s unlikely we’ll see Eurostars running north of London any time soon. While successive governments have paid lip service to “levelling up” the North, there seems to have been little change in their attitude to getting their chequebooks out for subsidies.

Mark Smith, a former British Rail manager whose popular website The Man in Seat 61 helps people travel internationally by train, tells The Independent:

“For regional Eurostars to be viable, we’d need to see something drastic change, for example Channel Tunnel security or border control requirements relaxed, or budget airlines curbed with an emissions tax – or even just a requirement to pay tax on their aviation fuel, currently available tax-free. Unfortunately, none of these seem likely to happen.”

That doesn’t mean train journeys from the North to the continent are impossible: it may not be the future we were promised, but it is possible to change trains onto a Eurostar in London.

“It’s a relatively easy change for passengers arriving at Euston or King’s Cross on trains from Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, York, Leeds, Manchester, Liverpool or Birmingham. It’s just a short walk to St Pancras for a Eurostar to Paris, Brussels or Amsterdam,” Smith notes.

The tracks that would have brought trains from the North to the Channel Tunnel rail link are all still there – though a crucial section through London is now part of the busy Overground, and lacks enough spare capacity to take international trains.

But other obstacles have also emerged. The question of border control has if anything got worse since the 1990s: when Eurostar first started running, passport checks took place on trains. Now they are done at stations, with each stop required to have its own secure “airside” departure lounge, adding extra costs to serving new destinations. Platforms for international services have to be fenced off to guard against stowaways, which is an operational pain and restricts capacity at stations.

And there is little hope for a relaxation of the rules that make it hard for services to pay their way, with the politics of cross-Channel border control being arguably more authoritarian than it has ever been.

Brexit has all but ruled out the prospect of Schengen membership for Britain, and added even more formalities to passport checks, which now take longer than ever. Since Britain left the EU, Eurostar has been cutting routes from London rather than adding them – only this week running its last service to Disneyland Paris, as border formalities have now made it impractical.

A glimmer of hope came in the 2010s. Early designs for HS2, the new high-speed railway meant to link London to the north of England and beyond, included plans to connect the new line directly to the Channel Tunnel rail link.

In theory, using HS2, a train might be able to take passengers from Manchester to Brussels in around three hours, or Birmingham to Paris in about 2hrs 45mins – very competitive with flying, once time at (and getting to) the airport is taken into account.

But the connection was taken out of the final design, in light of high costs and the fact that – given recent history and the problems that still exist – there was no guarantee it would ever be used.

For the foreseeable future, rail travel to the continent is likely to mean changing trains in London.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks