The ever-moving goalposts around sending military jets to Ukraine

Ideally, from a Ukrainian point of view, the UK might send a handful of planes, just to break the deadlock, and encourage Nato allies with plenty of more suitable planes to release them, writes Sean O’Grady

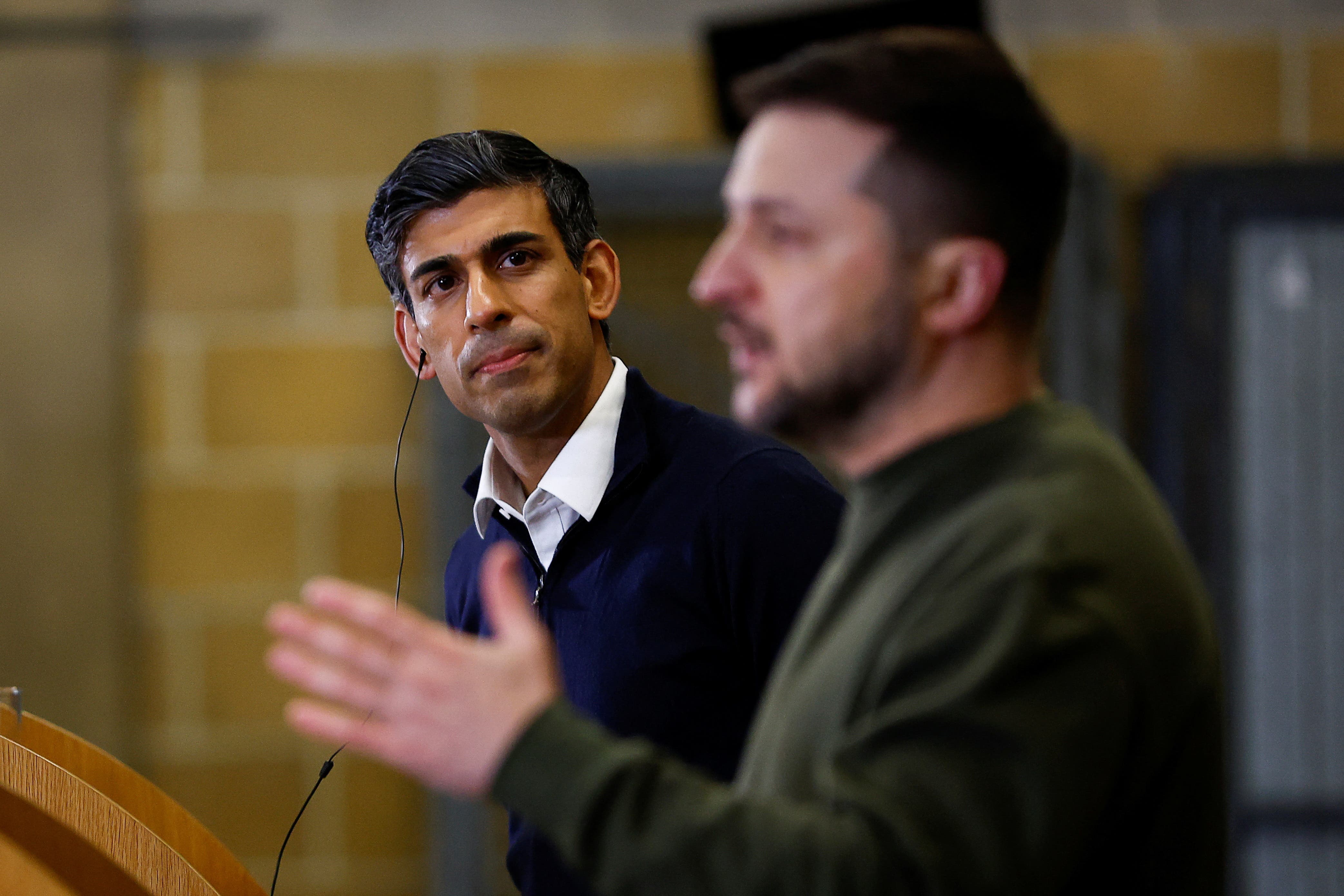

After the surprise visit by Ukraine’s president to London, Rishi Sunak, under pressure from Volodymyr Zelensky, Boris Johnson, MPs and public opinion, has indicated that the UK may be able to offer Kyiv modern fighter jets.

Why is Ukraine asking for fighter jets?

To help it win the war – in Zelensky’s words, as inscribed on then fighter ace helmet presented to the speaker of the House of Commons, Lindsay Hoyle: “We have freedom. Give us wings to protect it.”

In recent weeks, Western governments – after some delays and with caution – have committed vast amounts of munitions, missiles, air defence systems, artillery, armoured vehicles, drones and battle tanks to the Ukrainian armed forces. These are much better deployed, and safer from attack, if they can be deployed with the additional advantage of air superiority.

The Ukrainian air force is relatively small compared with Russia, and equipped with Soviet-era MiG jets. Hence the clamour for better equipment. Put crudely there isn’t much point in sending the most advanced and expensive tanks in the world, such as American Abrams and German Leopards, if the Russians can destroy them at will.

Did Zelensky’s visits to Washington, London and Brussels make any difference?

Yes. President Zelensky is proving a master at PR, and he knew exactly how to extract the maximum movement from politicians nervous about escalation against Russia and querulous domestic public opinion. He succeeded on the armoured vehicles and tanks (the Bradley fighting vehicles being a great prize), and shifted opinion his way on aircraft. But thus far without much firm commitment beyond helping to train pilots, which takes time.

Will the UK send jets?

Not for some time, if they do. But there has been a movement. Before the visit, the UK basically refused to countenance the idea – “it is not practical”. Since then the pendulum has been swinging. After Zelensky’s moving address to parliamentarians in Westminster Hall, and upsurge in sympathy, Rishi Sunak said that the UK has “been very clear when it comes to the provision of military assistance to Ukraine and nothing is off the table … When it comes to fighter combat air force, of course they are part of the conversation”.

However, soon after UK defence sources sought to emphasise that nothing can be done in the short term, and even longer term there will be problems. The main one is that the British prematurely retired their most suitable combat aircraft, the Tornado GR4 and the new advanced F-35 is simply to precious and packed full of top-end tech to risk falling into Russian hands.

The defence secretary Ben Wallace is now “actively looking at” whether the planes can be sent to help in the war against Russia.

He stressed that it would be part of a “long-term solution” plan, rather than the “short-term capability, which is what Ukraine needs most now”.

The long term, however, might be too late; and mean all the military aid given up to now wasted.

Ideally, from a Ukrainian point of view, the UK might send a handful of possibly elderly planes just to show leadership, break the deadlock, and encourage Nato allies with plenty of more suitable planes to release them to the Ukrainians, largely F-16s of the US and other Nato air forces. This would follow the pattern of when the British sent a group of Challenger tanks which triggered a much larger wave of Leopards heading eastwards.

What about training the pilots?

That is going ahead, and Zelensky inspected their progress when he was in Britain. However, again, air force sources say it may take much longer than it should to get the Ukrainian pilots used to Nato-standard equipment and tactics. At the moment the RAF is short of trainers and can barely train its own recruits. This was apparent during Air Chief Marshal Sir Mike Wigston’s evidence to the defence select committee last week. (When he was further discomfited by evidence of retired or reserve RAF pilots giving freelance training to the Chinese air force.)

What are other countries doing?

Depressingly little. The last time he was asked about jets President Biden gave a flat “no”, and it remains to be seen what the EU – France and Germany – can come up with. No country has sent fighter jets to Ukraine so far; early in the conflict, Poland and Slovakia have both offered decades-old MiG fighter jets, but transfers have apparently become entangled in discussions among allies.

What is the Russian response?

Hostile, of course. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov warned that sending jets would “make this conflict more painful and tormenting for Ukraine … and will not fundamentally change the outcome of the conflict”.

What does all this say about UK and Western defences generally?

It shows that the US remains a formidable superpower, the only one in the world with such reach, depth of capacity and comprehensive industrial base. In the case of European allies, it showed slowness in decision making and confirms German nervousness. On the other hand, Nato has emerged more united, expanded and stronger than it was a year ago.

For the UK it has been a salutary lesson on diplomatic leadership far outstripping a hollowed-out, under-equipped and emaciated defence that cannot make up for its manifest material weaknesses with its renowned bravery, professionalism and isolated centres of excellence. The Ukraine crisis should be no end of a lesson.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments