Could the ‘five families’ tag finally tip the Tory right into ridicule?

An alliance of factions dissolved into feeble abstentions over the Rwanda bill this week. They have emerged weaker from the episode, as John Rentoul explains

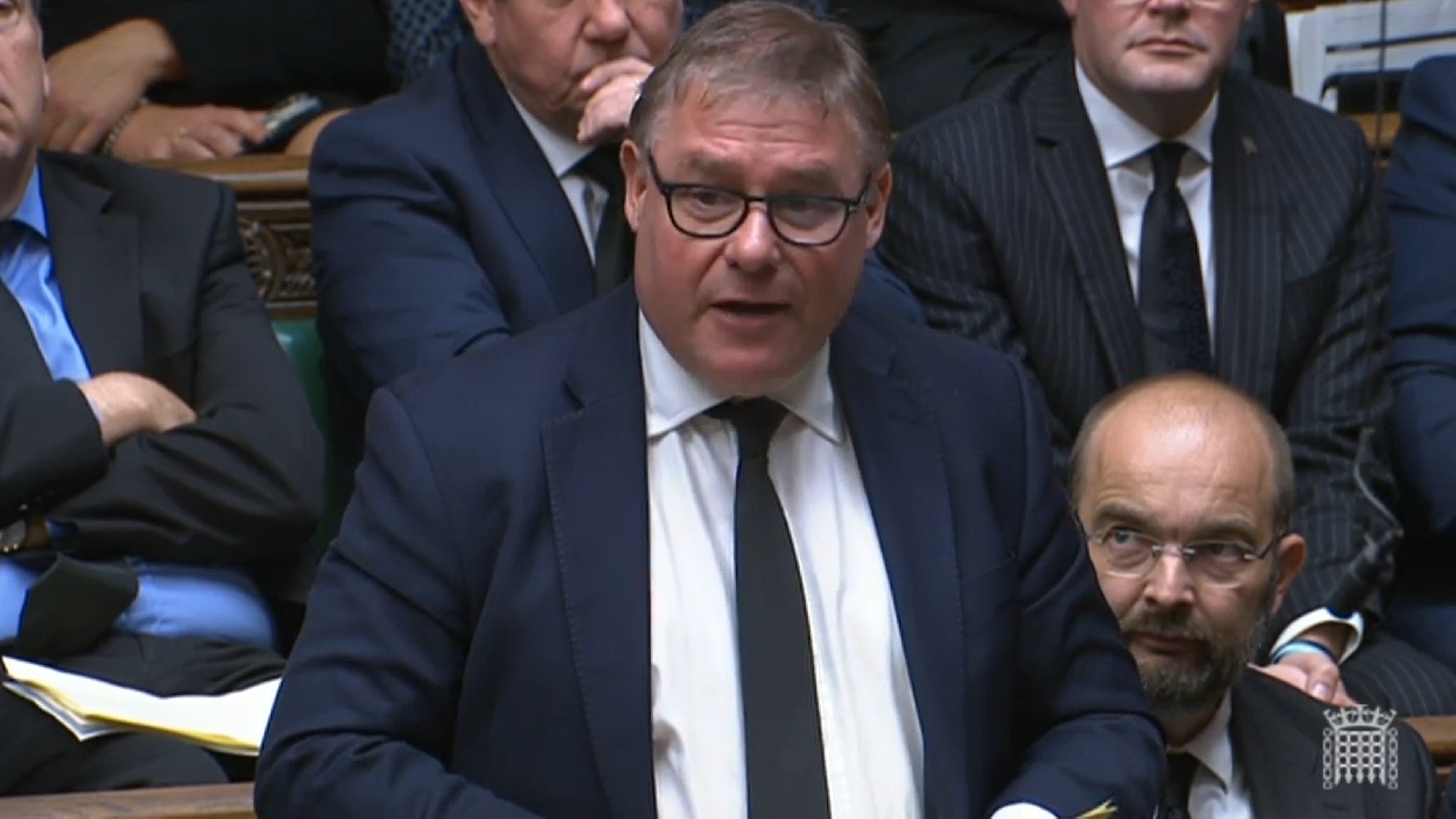

Mark Francois, the chair of the once-feared European Research Group (ERG), has now led his troops up the hill three times, only to march them back down again.

In July last year, Mr Francois provoked a backlash among members of the ERG when he prematurely went public with his support for Liz Truss in the leadership election triggered by Boris Johnson’s resignation. Other MPs in the group wanted to support Suella Braverman or Kemi Badenoch.

In October, Mr Francois addressed the TV cameras, flanked by other leading members of the ERG, to say that the group was unable to endorse either Rishi Sunak or Penny Mordaunt as the next leader.

Yet the myth of the ERG’s power, derived from the years of its role as the blocking minority in parliament standing in the way of Theresa May’s compromise Brexit, persisted.

So when the Rwanda plan divided the Conservative Party in much the same way that Brexit had once done, Mr Francois saw another chance to promote himself as the leader of the fundamentalists.

Who are the ‘five families’?

The problem for Mr Francois was that the ERG had been weakened by the turmoil of two leadership elections, the absorption of some ERG members into government and the different nature of the issues of immigration and asylum.

Rival factions on the Eurosceptic and anti-immigration wing of the parliamentary Conservative party have emerged, such as the New Conservatives, the US-inspired “populist” group which became something of a Braverman fan club.

There is also the Common Sense Group, which is trying to fight a culture war against “wokery”; the Northern Research Group, which organises MPs representing working-class former Labour seats; and the Conservative Growth Group, a Liz Truss leadership campaign grouping that has shrunk somewhat since the ignominious end of her brief premiership.

Mr Francois then tried to present himself as a spokesperson for all five groups, nicknamed the “five families” in an echo of mafia gangsterism.

How did that go?

Yvette Cooper, the shadow home secretary, couldn’t decide whether to make fun of the reorganisation and relabelling of “this carousel of Conservative chaos”, or to present it as a serious threat to the prime minister’s Rwanda legislation. She mocked “the implausibly named Conservative Growth Group, and if you thought that was an oxymoron, we also have the Conservative Common Sense Group”. But she went on to say that all these “fighting factions” have “one thing in common: they do not believe in the bill”.

It turned out, however, that most of the members of the five factions believed in the bill enough to vote for it, none of them voted against, and fewer than 30 Tory MPs altogether abstained.

How powerful will the five factions be in future?

Tory MPs who want the bill to go further in setting aside the UK’s obligations in international law claim to have allowed it to proceed with a view to amending it later. But they will come across a rather obvious problem, which is that they are in a small minority in the House of Commons, and that ultimately their choice will be to pass the bill or to unite with Labour to kill it.

That the bill cleared its first hurdle, Tuesday’s vote on the principle of it, with a solid majority of 44 suggests that there is insufficient appetite among Tory MPs for the “Samson” option of destroying the bill and potentially pulling the whole government down.

Every time Mr Francois marches his “five families” back down the hill, he appears to speak for fewer and fewer of his Tory colleagues.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments