Suella Braverman tries to revive the tradition of the deadly resignation speech

Since Margaret Thatcher was brought down by Geoffrey Howe’s ‘personal statement’, prime ministers have feared a cabinet colleague minister’s parting shot, writes John Rentoul

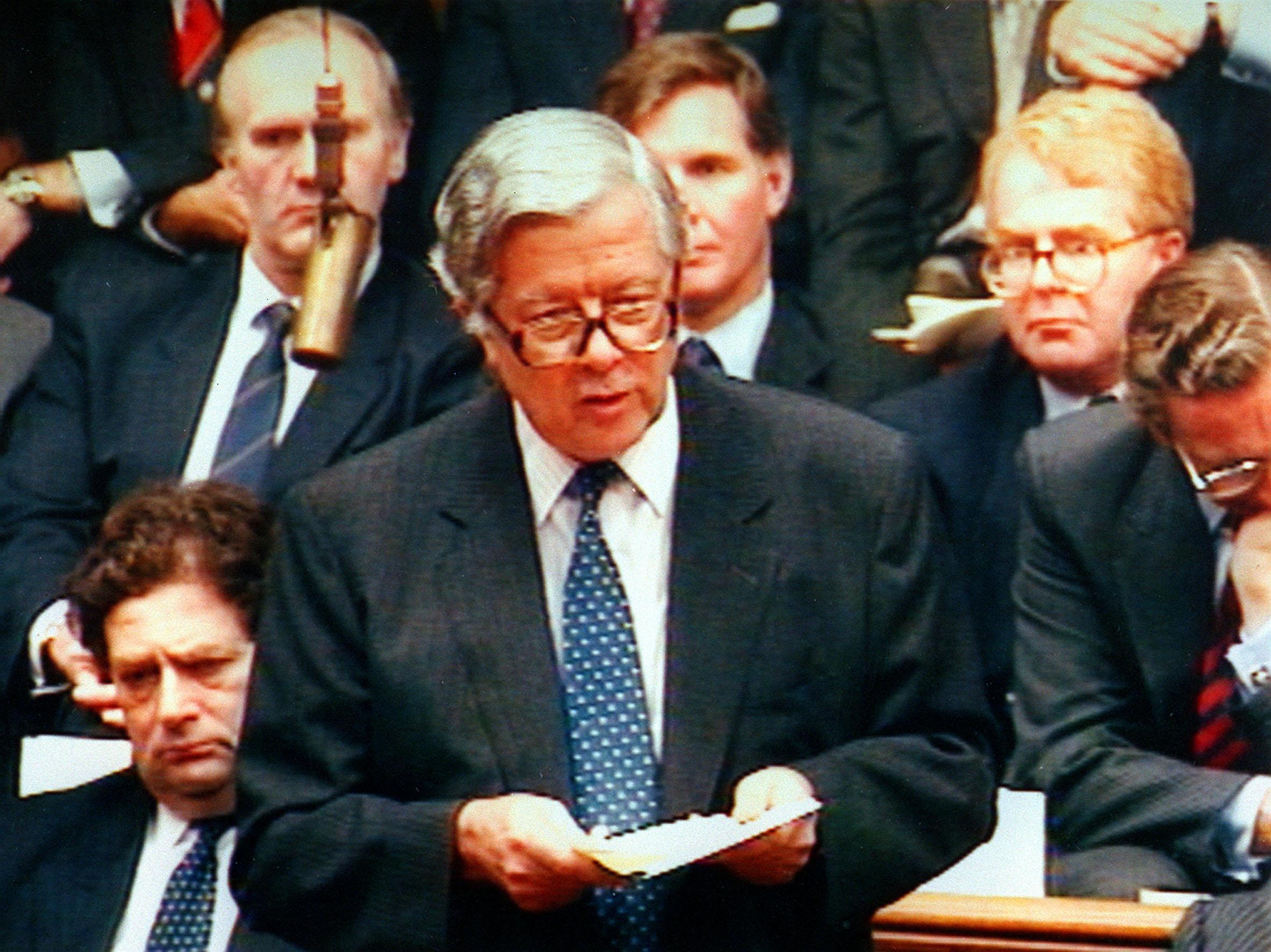

The mystique of the modern resignation statement dates from Geoffrey Howe’s devastating, unexpected assault on Margaret Thatcher in 1990. In a speech widely thought to be drafted partly by his wife Elspeth, the deputy prime minister in effect invited Michael Heseltine to launch the leadership challenge to Thatcher that led to her downfall.

The way for Howe’s speech was paved, however, by the apparently loyal resignation speech delivered by Nigel Lawson the year before. Lawson pretended to “accept without rancour” his departure from the Treasury, but he went on to say: “I would only add that the article written by my right honourable friend’s former economic adviser [Alan Walters] was of significance only inasmuch as it represented the tip of a singularly ill-concealed iceberg, with all the destructive potential that icebergs possess.”

That made it clear that his policy disagreement with Thatcher was fundamental, and implied that he was not the only senior minister to hold his views, but he ended his speech by saying that he had “every confidence” that the policies pursued by his successor, John Major, “will lead at the end of the day to a fourth election victory under the leadership of my right honourable friend the prime minister”.

The way Lawson and Howe’s speeches, 12 months apart, started and then finished the collapse of what had appeared to be the indestructible Thatcher premiership, meant that a “personal statement” in the House of Commons became historically significant.

A personal statement is granted by convention to any cabinet minister after leaving office. It takes a special place in the parliamentary timetable, after questions and ministerial statements but before legislative business. And it is expected to be heard in silence, with no interruptions or questions afterwards.

But the truth is that no resignation speech since Howe’s has lived up to the expectations of drama that it generated. Robin Cook’s speech setting out his arguments against military action in Iraq after his resignation as leader of the Commons in 2003 was much admired – although the striking feature of it, in retrospect, is how respectful it was of the sincerity of Tony Blair’s decision. (I also thought that the speech made by John Denham, who resigned as a junior minister, also over Iraq, was better.)

Clare Short, who voted with the government over Iraq, resigned after the invasion because she disagreed with the way that the US was running the occupation of the country. But she had missed her moment to have a dramatic effect on government policy.

Since then, the potency of the resignation speech has been diluted. The most powerful arguments tend now to be conveyed in a resignation letter. Boris Johnson, when he resigned over Brexit as foreign secretary in Theresa May’s government, put his case on paper, and invited a photographer to the foreign office to capture the signing of the letter, but he chose not to make a speech in the Commons.

Since then, Sajid Javid tried to revive the tradition, making not one but two resignation speeches. One in February 2020 when he was pushed out as chancellor by Dominic Cummings, Johnson’s No 10 adviser. And another in July 2022, when he resigned, minutes before Rishi Sunak did, in the successful attempt to drive Johnson out as prime minister. But that attempt to get Johnson out succeeded not because of Javid’s speech, in which he said “the problem starts at the top” and “enough is enough”, but because so many other ministers joined him in resigning at the same time.

Suella Braverman’s speech today is unlikely to go down in history, despite its neatly worded fake-loyal final line: “If the prime minister leads that fight he has my total support.” Everyone in the chamber understood the significance of the word “if”. But the former home secretary had already used her strongest lines in her resignation letter last month, in which she accused Sunak of “betrayal” and said he was “uncertain, weak, and lacking in the qualities of leadership that this country needs”.

But the Conservative Party has gone through too many leadership changes recently, and the next election is too close, to make another challenge likely. Braverman’s eyes may be firmly fixed on the leadership contest after the general election, but her attack on Sunak was too vitriolic to have wide appeal among Tory MPs, who still act as gatekeepers for leadership elections.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks