What the SNP arrest means for UK politics and Scottish independence

The SNP was already in a ‘tremendous mess’, as Sean O’Grady explains

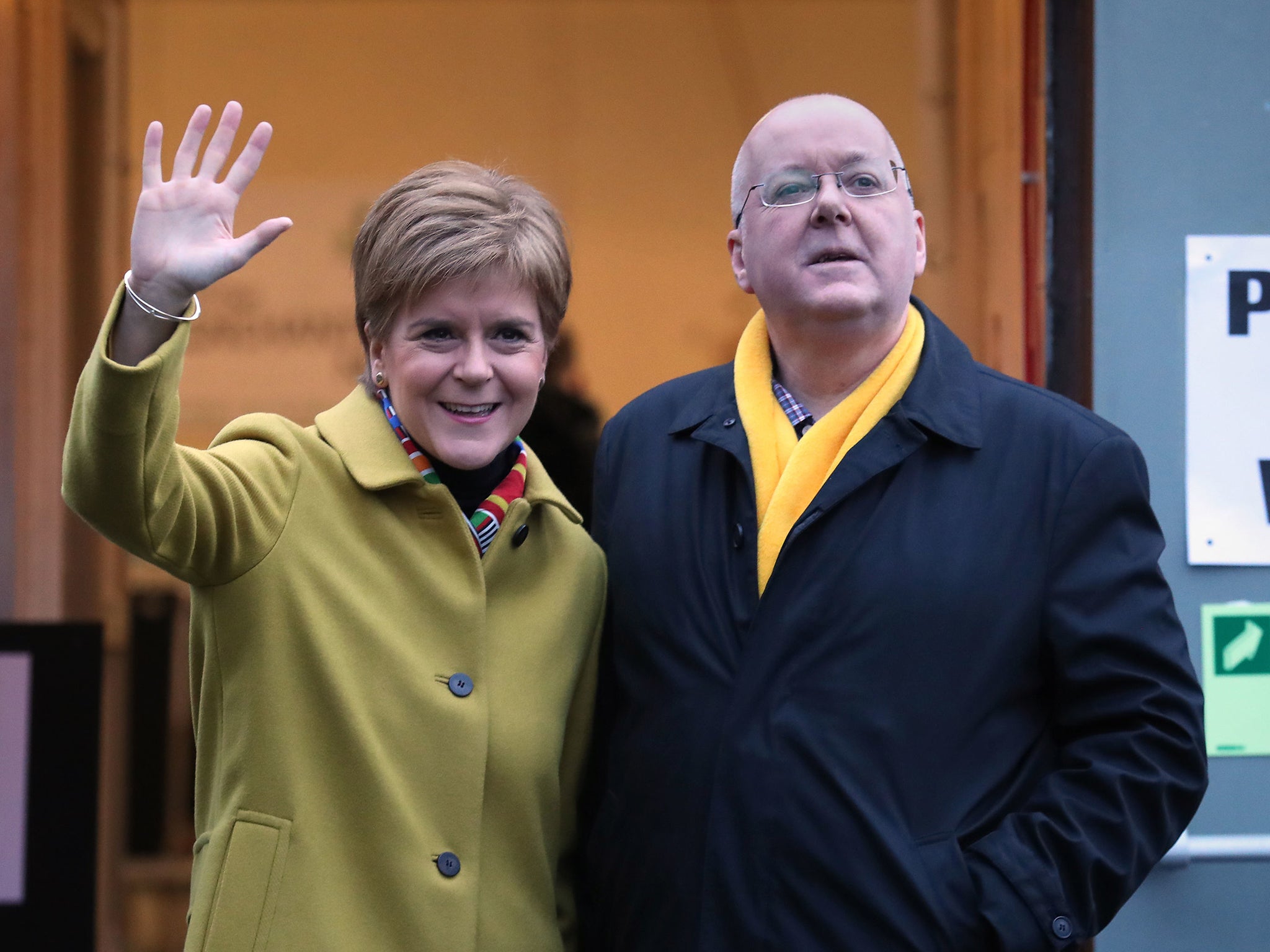

Peter Murrell, the husband of former first minister Nicola Sturgeon, has been arrested in connection with an investigation into Scottish National Party finances. He recently resigned as chief executive of the party and has been questioned after being taken into police custody. Police Scotland say they are carrying out searches at “a number of addresses”.

Is this why Sturgeon resigned so abruptly in February?

If it is, she’s certainly not saying so, and there’s been no word from her or Murrell since the arrest. In her resignation statement, she said she was standing down because her perceived divisiveness was becoming an impediment to independence and she thought she’d done her time. But only three weeks earlier, she had chirpily insisted she had “plenty left in the tank” – a nod to Jacinda Ardern’s departing comment to Kiwis that she no longer had “enough in the tank” to do her role justice. SNP finances have been the subject of attention for some time; observers will wonder if, at some point between her confident declaration and her decision to quit, Sturgeon might have realised what was to come.

How much trouble is the SNP in?

After 16 years in power, mostly without much serious competition, the party seems to be losing its mojo. In addition to the alleged financial irregularities, concerning some £600,000 of donations and other matters, membership also appears to have taken a hit. As the post-Sturgeon leadership began, the party had to admit it had lost 30,000 members over the previous two years, despite having dismissed reports of an exodus. Mike Russell, the party president, observed that it was “fair to say there is a tremendous mess and we have to clear it up”.

The recent leadership election was unusually acrimonious and personalised; Humza Yousaf only won on the second ballot, and by 52 per cent to 48 per cent against Kate Forbes, who’d been embroiled in rows about her faith and her socially conservative personal opinions. Yousaf offered Forbes a demotion to secretary for rural affairs; her allies let it be known that she had told him where “he could stick his offer”. Nor was third-placed Ash Regan given a role. According to the most recent opinion poll, Yousaf already has a negative approval rating of -7 per cent; he also faces formidable challenges on the economy, schools, the NHS, an overspent ferries project, and the stalled Gender Recognition Reform Bill. Plenty more ructions to come.

What is the political impact?

Even before Murrell’s arrest, SNP ratings had been sliding, mostly to the benefit of the Scottish Labour Party. The next Holyrood elections won’t be until 2026, so attention is now focused on how the party might perform in the next UK general election, which is due by the end of 2024. Given that the SNP’s travails are likely to continue for some time, and in the context of a wider Labour revival, the likelihood must be that the SNP will lose a significant number of Westminster seats.

In the most recent poll ratings, the SNP is still the leading party, but on around 36 per cent support it has lost about 10 percentage points on its showing in the December 2019 general election. By contrast, Labour has improved on its 18.6 per cent (and just one parliamentary seat) to about 31 per cent. The Conservatives have declined in Scotland since 2019, as elsewhere, but not quite as sharply as the SNP has fallen. The Liberal Democrats are a little ahead of where they were then.

Conservatives recently urged pro-union voters to support Labour where tactically astute; but Labour, which has less to gain from the tactic, is not reciprocating.

Such are the vagaries of the Westminster first-past-the-post electoral system in Scotland’s four-party environment, it’s difficult to judge how this might pan out; in addition, boundary revisions complicate the picture, and overall Scottish representation in the Commons is set to drop by two seats to 57. However, it seems that the SNP might lose about 19 of its present 48 seats in the Commons. The bulk would fall to Labour, mostly in central-belt strongholds such as Glasgow, while a couple would actually go Conservative and the Lib Dems would pick up one, in Fife. As a result, the SNP might concede its status as the third party in the Commons to the Lib Dems, with the loss of attendant privileges (such as being allocated two questions at Prime Minister’s Questions, and holding some select committee positions).

An early sign of the way trends are developing might come at a by-election in Rutherglen and Hamilton West; the sitting independent MP, Margaret Ferrier, elected for the SNP in 2019, has been sanctioned by the Commons privileges committee, leaving the door open for a recall petition and a by-election in what is a highly winnable seat for Labour.

Where does this lead the campaign for independence?

In the doldrums; the SNP is to discuss its best path to a further referendum – and then winning it – at a special party conference. The recent leadership election exposed divisions on strategy, and Alex Salmond’s small Alba Party, more impatient and radical on the issue than the SNP, is also still active.

There is zero chance that the next UK government, whether it is Labour or Conservative, will grant a referendum request, even if the SNP holds the balance of power at Westminster. Aside from that, support for independence is running nowhere near strong enough for the independence cause to be confident of a referendum victory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments