Why does everyone keep helping the SNP?

The party is facing a series of issues and its members are squabbling and split. But, writes Sean O’Grady, while its rivals continue to make missteps and mistakes, it has little to fear

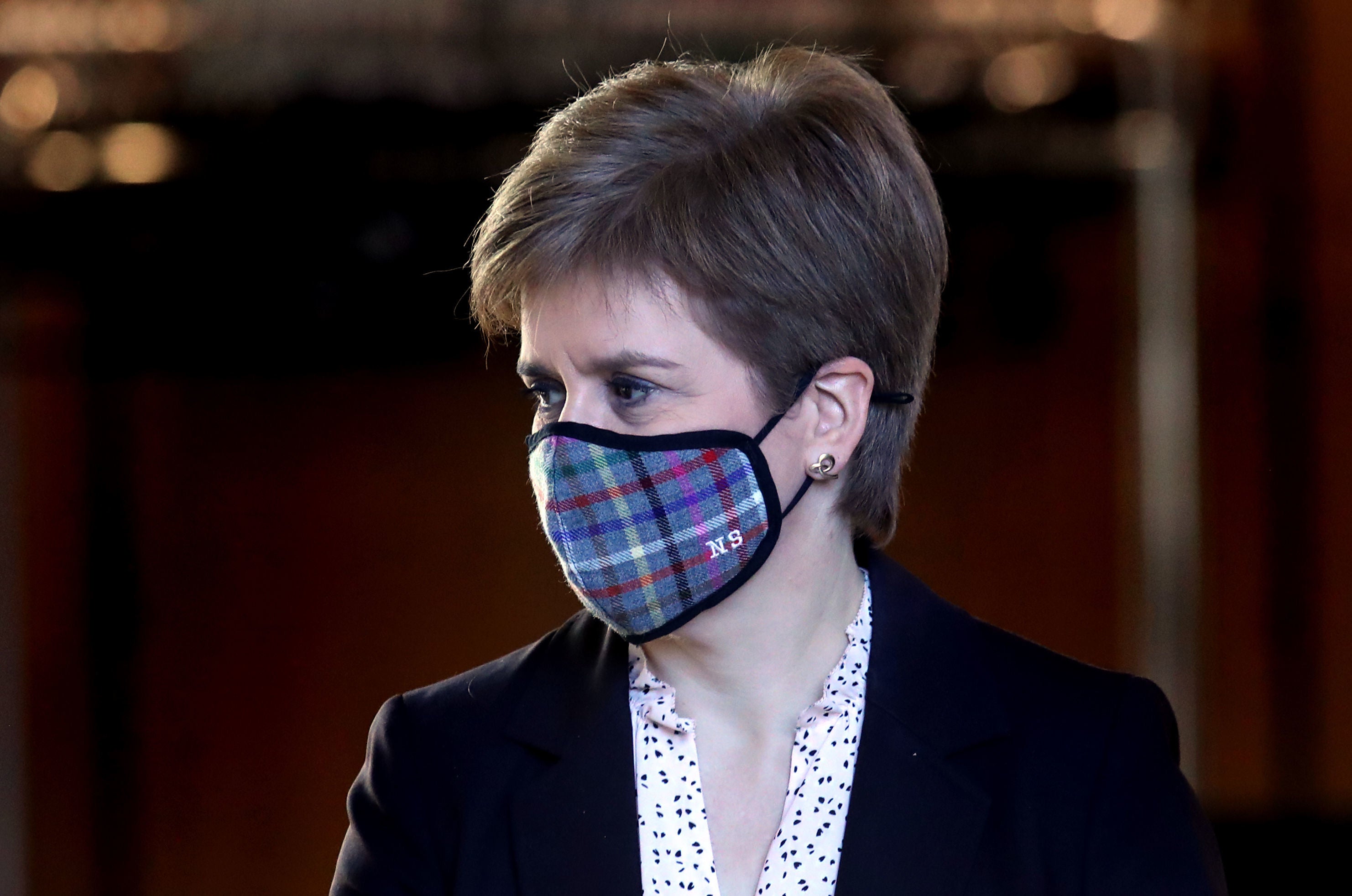

Given that the SNP has been in power since 2007 and that Nicola Sturgeon has been first minister for the last six momentous years, it is surprising, if not miraculous, that the party is still riding high in the opinion polls. While a little off the highs of last autumn, the Scot Nats still register solidly above 50 per cent, and are well on course for a substantial victory at the elections for the Scottish parliament in May. With that will come a pledge, and arguably a mandate, for a fresh referendum on independence. On that issue, too, the party is currently on track to achieve its historic aim.

So, treble Scotches all round? Apparently not. So far from concentrating on delivering its precious cargo of Scottish nationhood safely into harbour, the SNP is squabbling and split. Fortunately the voters appear to have taken little even notice of the arguments for them to defect to any of the unionist alternatives, but that may change. What is going on?

It’s complicated, but the key seems to be that the wrangling seems mostly more personal and confined to subjects, rightly or wrongly, not at the top of voters’ minds just now.

Take the sacking from the Westminster frontbench team of the experienced and successful Joanna Cherry. A QC, Cherry was a doughty and smart opponent of Brexit and the illegal prorogation of parliament last year. Yet this seems to have counted for nothing, and her views on women’s rights and trans rights, and possibly on the leadership style of Nicola Sturgeon, apparently account for her fall. She has also advocated what might be called the Irish route to independence. Under this proposition a legal referendum on Scottish independence, which can only be granted, in effect, by Boris Johnson is in fact unnecessary. Ireland overwhelmingly elected nationalist or Republican MPs to Westminster and the informal assembly in Dublin in 1918 and after, and they negotiated with the British cabinet, Irish independence, albeit against a background of bitter conflict and violence (that was shortly to turn into civil war and the Troubles that have endured, on and off, for a century since). Sturgeon is adamant that only a referendum sanctioned by Westminster can be contemplated, and the agonies of Catalonia after its unofficial referendum point, on that view, to the dangers of pursuing alternative and questionable routes to nationhood.

Such debates may well seem a bit remote to much of the Scottish public in the middle of a pandemic. Whichever view they cleave to, the struggle for the referendum can be dealt with after May this year. What is indisputable is that there is a majority for independence – but is far from overwhelming.

Was Alex Salmond treated fairly over allegations of sexual misconduct when they came to the attention of the Scottish government and first minister? He was acquitted of all charges and there is a further Scottish parliamentary enquiry going on now. The party is split between friends of Alex and friends of Nicola, and Alex and Nicola are no longer firm friends. It’s a big story, this unarmed combat between two first ministers, and especially so when Sturgeon’s husband, Peter Murrell, is involved as chief executive of the SNP. There are bizarre debates about the status of meetings in the Sturgeon family’s front room and much arcane procedural wrangling. Yet it is also essentially a matter of history, and will not, or ought not, in itself have any great relevance for the national question. Only if the impression or reality of division makes the SNP seem incompetent that it might damage the SNP’s standing.

It is just as well, then, that Brexit and the Covid crisis has left Sturgeon with a far more professional reputation and seemingly in firmer control of affairs than Johnson, or indeed any of her local rivals who’ve fallen by the wayside in the past year or so. Richard Leonard, leader of Scottish Labour, is the latest to quit, after the Scottish Tories’ went through three leaders. No matter that Scotland’s Covid performance has been broadly in line with the rest of the UK, the first minister has impressed in her daily press conferences and obvious sense of duty. If nothing else, Sturgeon has been lucky in her enemies.

And that seems to be the point. There are plenty of unanswered questions about independence – the currency, terms of EU re-entry, soft or hard border with England, the carve up of UK assets and debts, who gets RBS. The SNP’s record in government isn’t unimpeachable, particularly in areas such as education. The party is clearly becoming more factional on Salmond, trans rights, economics and how militant they should become in the struggle for independence. Yet however scrappy the SNP get, their opponents still contrive to make them look good. Nowhere is this more striking than in the case of Johnson, whose very presence on Scottish soil always resembles a calculated wind-up. It might amuse Johnson to annoy “that bloody Wee Jimmy Krankie woman”, but he is doing her work for her, and he would not survive if he lost the union or even appeared likely to. Of all the protagonists, it is the British prime minister (and nation) that has the most to lose.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments