How is the furlough scheme being withdrawn – and what are the risks?

There are warnings of mass redundancies as support for employment is phased out over the coming months, writes Andrew Woodcock

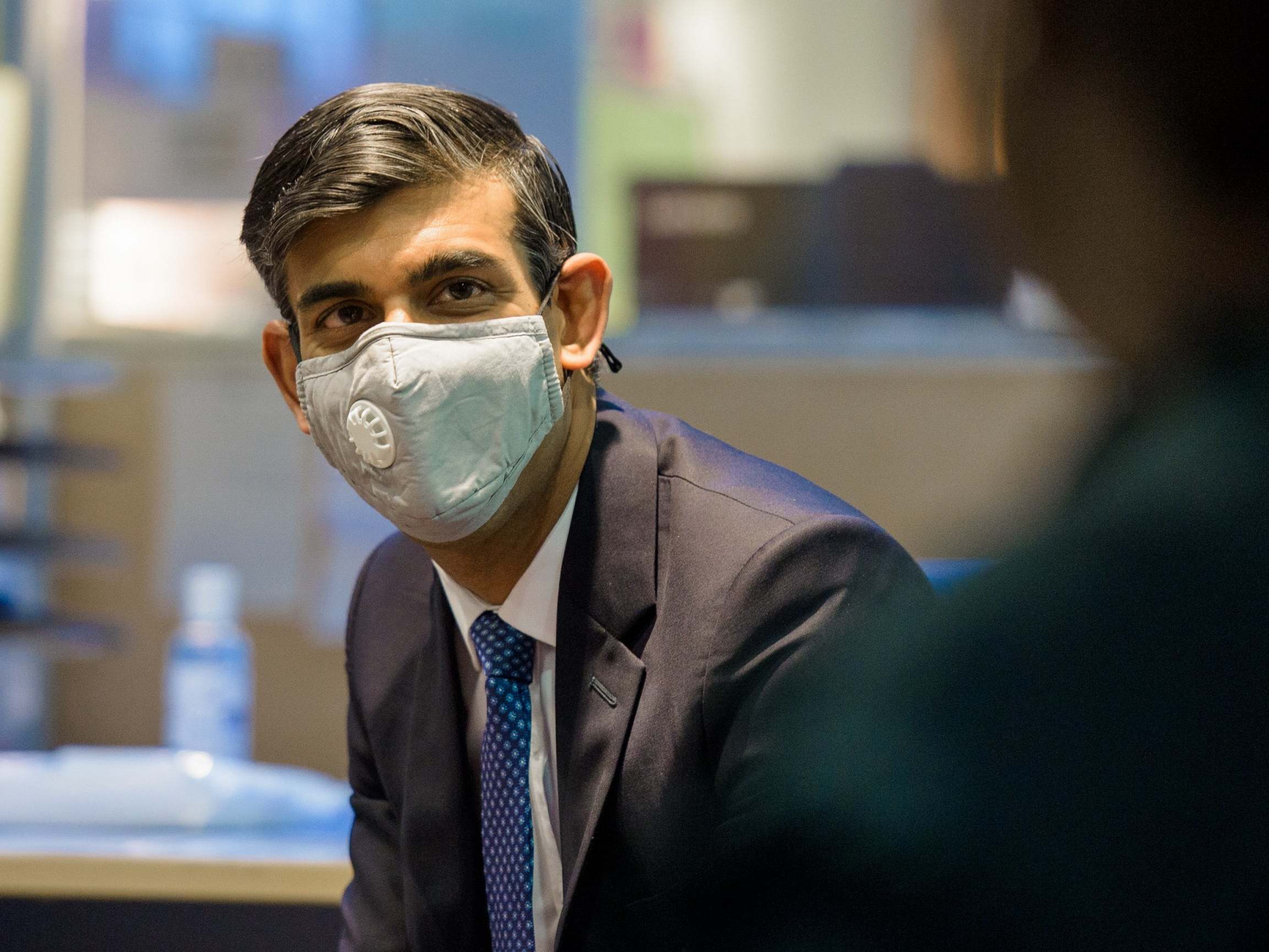

Businesses are now having to contribute towards the cost of keeping inactive workers in jobs during the coronavirus crisis, as chancellor Rishi Sunak’s furlough scheme begins a gradual rollback leading to its closure at the start of November.

The change has sparked warnings of waves of redundancies as employers are faced with growing costs to retain staff who cannot work as normal because of social-distancing rules.

Ministers say Mr Sunak’s job retention scheme provided an income for millions of workers – and maintained their links with employers – during the worst months of the first Covid-19 wave. But Labour says his “one size fits all” approach to winding it down risks mass job losses, which could be avoided if it was extended for the worst-hit sectors.

The job retention scheme was opened for applications on 20 April to stave off mass redundancies among businesses forced by the coronavirus lockdown to close their doors.

Since then, more than 9.5 million workers from 1.2 million employers have benefited from cash grants worth up to 80 per cent of monthly wages up to a maximum of £2,500 while they are unable to work.

At its height, the equivalent of one-third of the entire private-sector workforce was effectively being paid by the state.

But Mr Sunak announced in May that the scheme would be gradually scaled back over the following four months to bring an end to escalating costs, which the Treasury last week revealed had reached a massive £31.7bn.

From 1 July, employers were permitted to bring furloughed staff back on a part-time basis, while still claiming the grant for hours not worked.

This month, the state will continue to subsidise furloughed workers’ salaries, but employers will be required to pay national insurance and pension contributions for the hours the staff member is on furlough.

The Resolution Foundation think tank has calculated that the change will cost employers an average of £70 a month per employee – or 5 per cent of their pre-furlough pay.

In September, the subsidy will be reduced to 70 per cent of wages up to a monthly cap of £2,187.50, and from 1 October it will drop further to 60 per cent of pay up to a maximum £1,875.

But crucially, employers will have to top up the payments to ensure furloughed staff continue to receive at least 80 per cent of their normal wage up to a maximum of £2,500.

For staff unable to return to work even on a short-time basis, this will mean businesses having to pay out up to £312.50 for each employee in September and £625 in October, on top of the NI and pension contributions.

Under Mr Sunak’s plans, payments will end altogether on 1 November.

But he is offering a job retention bonus to encourage employers to keep staff on, with £1,000 on offer for every formerly furloughed staff member who stays in their post until the end of January on a salary of at least £520 a month.

At a potential cost of more than £9bn, the bonus scheme, unveiled on 8 July, has come under fire for creating the risk of a massive “deadweight” cost as huge sums are paid out in relation to employees whose jobs were never under threat.

Mr Sunak has admitted it will be impossible to know how many jobs the bonus has saved, and critics claim the £1,000 payment is not large enough to tempt employers to preserve jobs which are not financially viable.

Economic think tank Niesr has branded the closure of the furlough scheme this autumn a mistake, warning it will drive up unemployment by as much as 1.2 million by Christmas.

Extending the scheme until the middle of next year would cost about the same as the bonus and would be more effective at saving jobs, the think tank said.

And the Federation of Small Businesses urged the government not to “pull up the business-support drawbridge”, calling for targeted help for sectors unable to get back to normal operations.

“Even with critical emergency measures in place, jobs are sadly being lost in the here and now,” said FSB chair Mike Cherry.

“Further targeted support for those having to remain shut is urgently needed, especially in areas where local lockdowns are in place.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments