Why the state of our teeth could become an election issue

Two-thirds of children did not see a dentist last year, and pressure on health services is likely to be an electoral problem for Rishi Sunak, says Mary Dejevsky

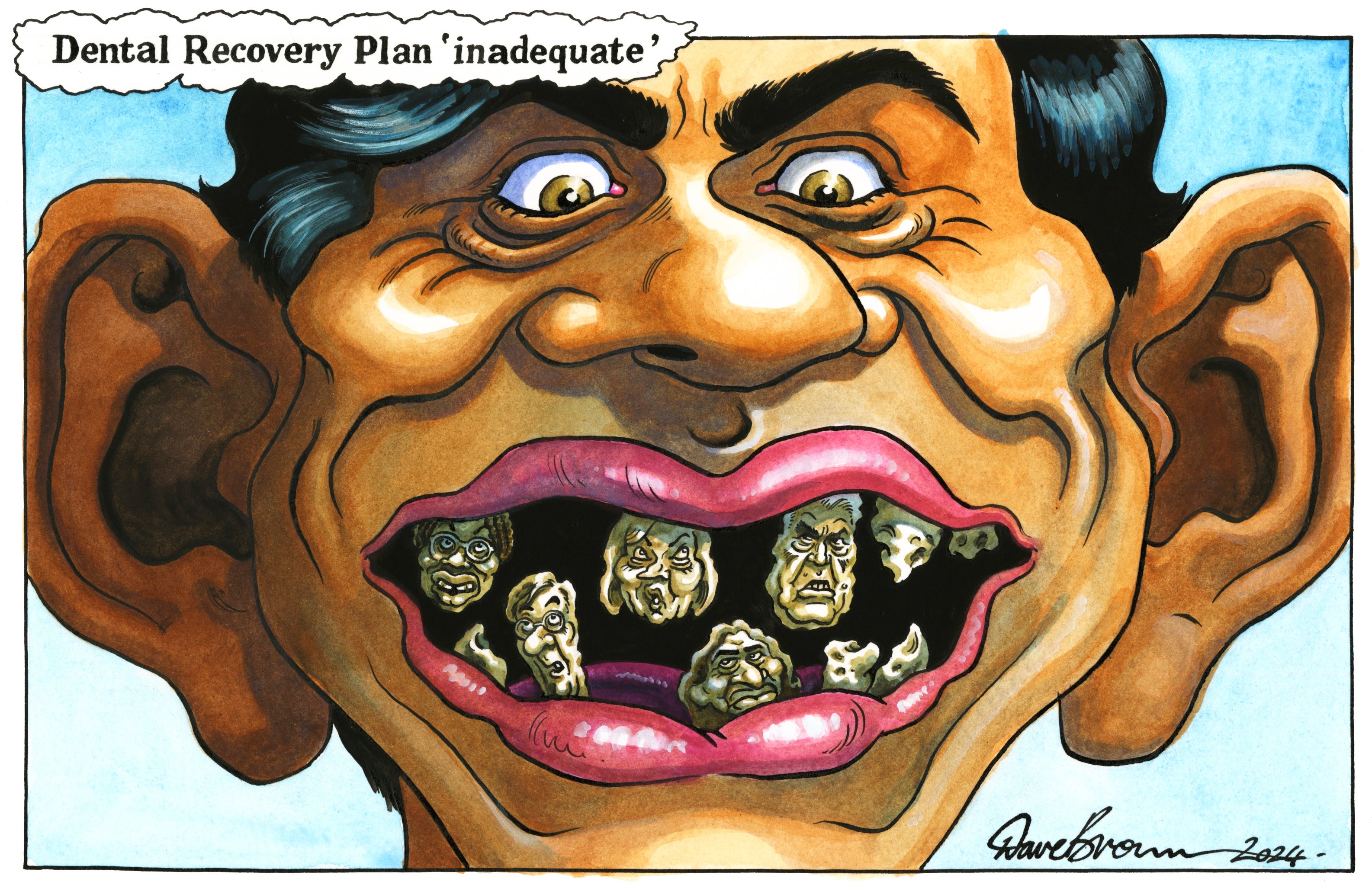

Victoria Atkins, the health secretary, and Rishi Sunak were both in the firing line in the Commons over what is being called a crisis in dental services, after new financial and other measures were announced to improve provision. Dentistry could now join hospital waiting lists as a potential election issue for the prime minister.

Why are dentists an issue now?

Perhaps the most graphic reason is pictures of a huge queue of people trying to register as NHS patients at a new dental surgery in Bristol; the images seemed to sum up the difficulties faced by many across the country. Another reason was the announcement this week of incentives the government says will ease the shortages in NHS dental treatment.

Is there really a crisis in NHS dental care?

You don’t have to believe all the reports of people resorting to DIY dentistry – although some are clearly true – to be convinced that dental provision is in the same state as hospital or GP care, if not worse. Reasons for this include the pandemic, where the physical proximity required for treatment and checks discouraged visits to dentists and dentists from practising. Dentists also cite the NHS fee structure, which they say worsened significantly under the Blair government, to the point where state funding now barely covers treatment provided, driving many dentists into the private sector.

More evidence of a crisis comes from surveys of children. Two-thirds of children did not see a dentist last year, while tooth decay is the main reason for hospital admissions of children between six and 10. These last figures prompted Labour to propose toothbrushing sessions at primary schools (to much scorn from Conservatives and talk about a “nanny state”). It does not take much imagination to see what the condition of children’s teeth today could mean for the nation’s health tomorrow.

What is the government proposing?

Victoria Atkins has presented a “recovery plan” that includes a £20,000 “golden hello” for up to 240 dentists setting up in areas of the country with poor access to NHS care. There will also be higher payments for dentists seeing patients who haven’t had a dental appointment for two years, and increased fees paid for more complex work. Despite the nanny-state jibes for Labour’s proposals, there is also to be a tooth-care campaign for schools. In a throwback to what seems like the distant past, fluoridisation of water is to be expanded.

However, the British Dental Association says these measures are little more than rearranging the deckchairs. Pushing dentists into NHS provision will also be difficult since newly qualified dentists can move directly into private practice.

Was there ever really universal provision?

While “free at the point of use or need” has been the mantra of the NHS, free dental treatment ended early in its history. Charges, even for NHS treatment, were introduced as early as 1951 and have remained with precious little public protest.

This may be because relatively large groups are exempt from such fees – including those under 18, pregnant women and new mothers, and recipients of certain state benefits (though not pensioners). Although far below most private charges, NHS fees can nonetheless seem steep; treatment is banded, with band 1 (the simplest) set at £25.80, rising to £306.80 for a band 3 course of treatment. However, these prices become academic if you cannot find a dentist who provides NHS treatments in the first place.

Could teeth become an election liability for the government?

That will depend on a number of factors, including how prominent other issues might become between now and an election, which now seems likely to be in October. The chemical attack on a woman and her children in London has probably raised the issue of immigration up a few notches in public concern, but NHS waiting lists and the increasing numbers choosing, or feeling compelled, to go private are likely to remain a big issue.

Accounts of dental horrors tend to remain distinct from other complaints about the NHS. Still, they feed into the same debates about inadequate provision and the cost of private treatment to patients who can ill afford to pay but find it increasingly hard to find timely treatment. The more patients are channelled reluctantly into the private sector, the more aware voters are likely to be of the glaring differences between NHS and private care.

What happens in other countries?

In many countries where there is insurance-based health provision, such as France, Germany, Italy and the United States, many plans cover dental treatment. In much of the EU, treatment is free for those deemed unable to afford it. However, for those without insurance or with only limited coverage, the gap between charges for state and private provision tends to be narrower than it is in Britain. The difficulties experienced in trying to access dental treatment have led to some expatriates, especially from central and eastern Europe, choosing to return to their home countries to access services there.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments