Could Lee Anderson’s defection to Reform UK cause serious problems for the Tories?

As the former Tory deputy chair announces his departure to Richard Tice’s Reform Party, Sean O’Grady asks whether Anderson will prove to be a heavweight political adversary to Sunak – and trigger wider unrest among a Tory party already in turmoil

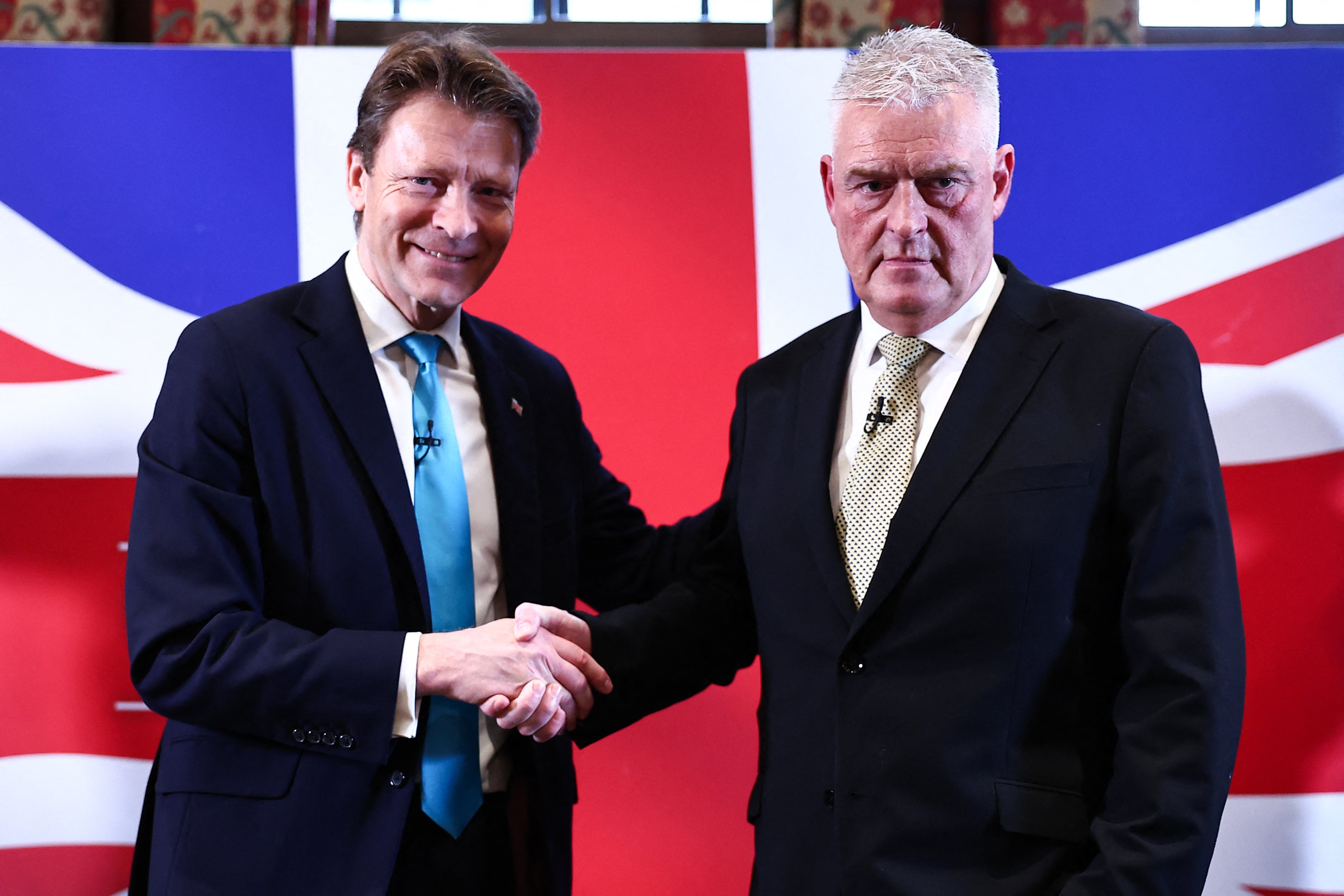

A beaming Richard Tice, leader of Reform UK, surrounded by no fewer than three giant union jacks, paraded Lee Anderson to the media like a prize bullock at a county agricultural show. Here, we are asked to believe, is a heavyweight political beast; a former Conservative deputy chair and the MP for Ashfield, who speaks for millions and has decided to put the nation first by defecting to Reform UK. Anderson’s potent seed will invigorate Reform, which has already made some remarkable progress in the opinion polls and scored respectable results in by-elections. But there must be doubts about the strength and usefulness of the charge Anderson is about to make at the Tories...

Will there be a by-election?

Sadly, no sign of that. When Reform’s ancestor, Ukip, managed to get a couple of Tory MPs to defect, both resigned from the Commons in order to fight by-elections, and they both won. That was in 2014, and conditions for their victories were somewhat propitious – for various reasons, the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats were all fairly weak, while Farage and Ukip were on a protest-vote roll (so much so that they’d pushed David Cameron into promising an EU referendum).

However, the chances are now that Labour would take the seat easily, and the Reform coup would be turned into a signal defeat. Besides, Anderson could claim – with some justification – that there’s a general election around the corner anyhow.

What will be the effect on the Conservatives?

Further destabilisation. Though Anderson tended to divide opinion nationally and wasn’t the most popular figure within the parliamentary party, there is a significant group of his fellow MPs who share many of his concerns about the government’s failures, and Anderson is certainly popular with the grassroots.

His departure for Reform UK, therefore, raises questions once again about Rishi Sunak’s leadership – although, this close to a general election, there really isn’t much time at all for the Conservatives to do anything about that, even if they were inclined to do so. At the very least, it’s a distraction and an embarrassment that the party doesn’t need given its poll ratings; at worst, it will trigger a wave of defections to Reform among MPs, party members and voters, pushing the “old” Conservative Party into oblivion – and/or rebirth as a “real” Conservative grouping, allied or merged with Reform UK.

What does it tell us about Sunak’s judgement?

He made a mistake with Anderson by appointing him deputy chair, with an additional salary, and encouraging him to express his extreme “common sense” views in a futile attempt to retain red-wall voters in the Midlands and the North. These were the folk who’d come over to the Tories for the first time in 2019, and were now badly disillusioned by Partygate, Liz Truss, and the lack of “levelling up”.

As Anderson once pointed out, shrewdly enough, the Tories won in 2019 thanks to a trio of factors: Boris, Brexit and Corbyn. At the next election, all those factors will be absent, and thus a prominent voice in the “culture wars” is likely to be needed to win votes. Anderson was supposed to be the man for the job.

The main problem is that Anderson’s rebarbative language could also be heard by a much less receptive audience in the blue-wall seats down south – seats that are now in increasing jeopardy. When Anderson went off-piste over a vote on the Rwanda plan – too soft for Anderson’s taste – he quit his nominal role, and Sunak was mildly humiliated. That was probably the end, in terms of his role in the party. Anderson was patronised by Sunak, and Anderson patronised red-wall voters; none of it was an edifying sight.

What about Nigel Farage?

A tantalising question. He’s been pretty quiet about things. Farage is undoubtedly a talisman for the hard right, as well as an energetic campaigner and a gifted propagandist. However, his relationship with Reform UK is ambivalent. He is actually the majority owner of Reform UK Limited, as well as its “president”, and in reality controls its most important decisions.

It is not a conventional political party with leadership elections, sending delegates to conferences and debating policy or taking part in any irksome democratically elected executive committees – the latter being a feature that especially irritated Farage when he was leader of the fissiparous and disputatious Ukip.

Despite all that, Farage seems content to be a well-paid presenter on GB News and a warm-up act for Donald Trump, and hasn’t expressed much interest in campaigning for Reform, let alone leading it or standing for parliament yet again.

Why does Reform UK want Anderson anyway?

Fair question. While any defection generates headlines and a sense of momentum, and can boost a party’s fortunes, Anderson carries some political baggage, not least his most recent Islamophobic remarks about Sadiq Khan, which the Tory leadership said were “unacceptable” and “wrong”. He refused to apologise and lost the whip.

Even by Reform standards, Anderson’s views are fairly extreme and bluntly expressed. Ben Habib, the deputy leader of Reform, expressed his doubts quite recently: “I would be quite circumspect about anyone who can’t express themselves accurately, clearly and in matters of great sensitivity without actually being able to identify properly what the issue is.

“I need to understand what he means by Islamist. I need to understand what’s in his mind. Does he think there’s a group of extreme Muslims controlling Sadiq, or does he think Sadiq is a prejudiced individual who’s perpetrating divisive politics? And I’d say Sadiq Khan is probably the latter, not the former. Lee clearly hasn’t got a grasp, in my view, of the language required to identify and address the problem.”

Conversely, Anderson has been fairly rude about the Reform leader, Tice, once calling him a “pound-shop Nigel Farage”: “I get on with Richard reasonably well, but I would say this: he’s not Nigel Farage; he’s not the leader that Nigel Farage was.”

As the election approaches, Anderson, as a sitting MP, will inevitably attract attention and take media appearances away from Tice – and, possibly, Farage. Moreover, there is plenty of scope for Anderson to make gaffes and open up divisions within Reform. He will also have to eat his words, such as when he previously dismissed the idea of supporting Reform because it would make a Labour government more likely.

On his record, Anderson will prove an awkward colleague. No less than the far left, the hard right is well able to splinter and split over relatively trivial differences.

Will Anderson be returned at the general election?

The odds are against him, given the polling, but politics in the Ashfield constituency are made much more complicated by the presence of the Ashfield Independents, who dominate the local district council and send a significant contingent to Nottinghamshire County Council. They despise Anderson, but are a wild card electorally as an alternative to the main parties and to Anderson himself. At the last general election, the Ashfield Independents’ leader, Jason Zadrozny, stood against Anderson and others and won 27.6 per cent of the vote, compared with the Conservatives’/Anderson’s 39.3 per cent and 5.1 per cent for the Brexit Party, the precursor of Reform UK.

As a political curiosity, Anderson replaced the last Labour MP, Gloria De Piero; he had previously been a Labour man and her office manager. His Brexit Party opponent in 2019 was Martin Daubney. All three are now GB News presenters.

Will Reform win the general election?

No, and they’ll be lucky to win a single seat. Their role and aim is to take over what’s left of the Tories. In which case it’s quite likely that Anderson would find himself deputy chair again, but in a more congenial setting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments