How do you solve a problem like HS2?

The Conservatives may end up paying a political price for a project that will struggle to live up to the early hype, writes Sean O’Grady

What was once a vaunted and ambitious project now looks closer to a millstone around the neck of the prime minister, Rishi Sunak, and his government.

Is HS2 in trouble?

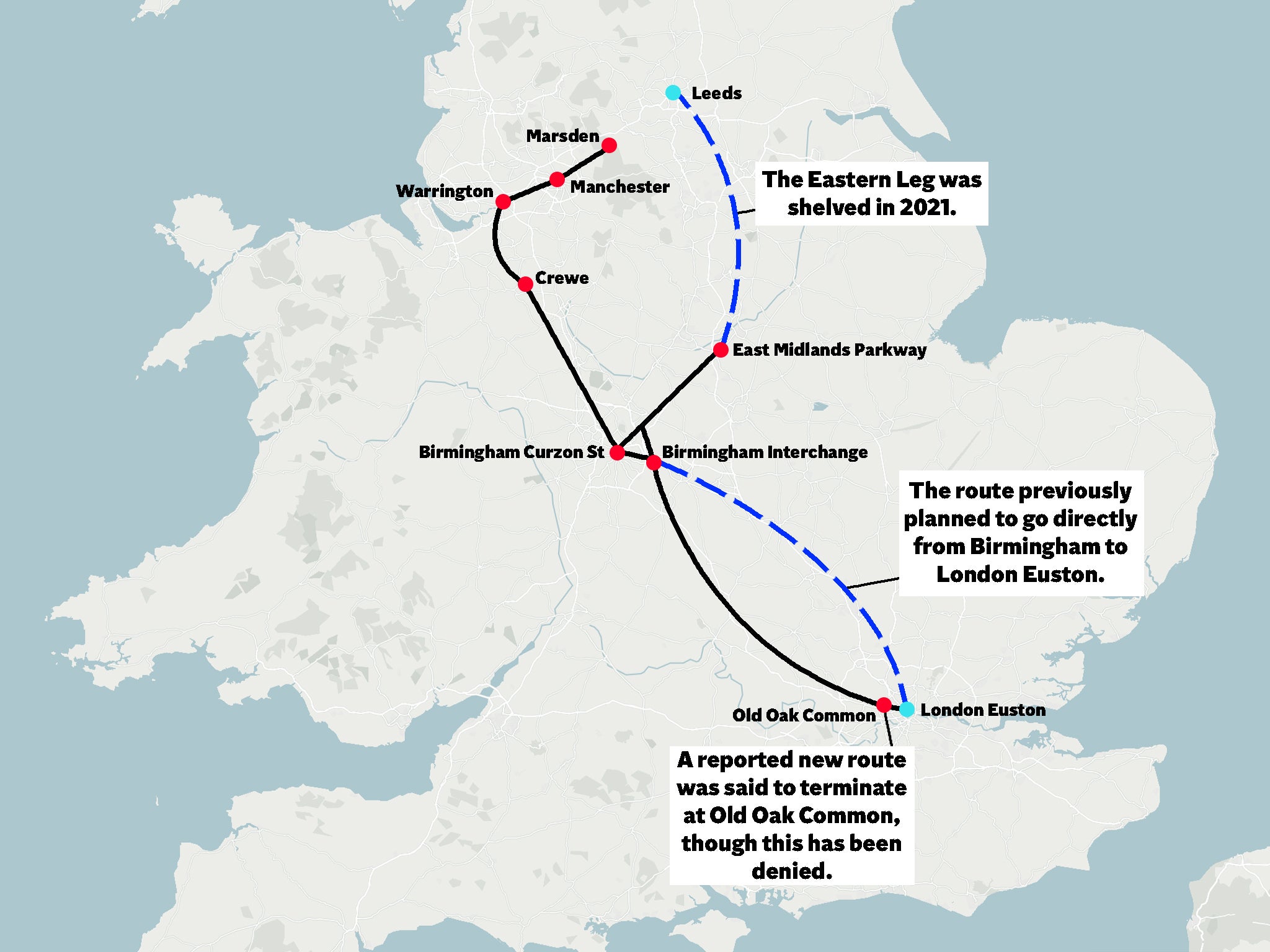

Yes. Again. Reports suggested a radical downgrade in its pace and/or ambition on the grounds of rapidly escalating costs – of labour and materials after Brexit, of post-pandemic disruptions, and of the price of energy, ramped up by the war in Ukraine. Several options have apparently been discussed in government. These include various permutations of the following measures: ending the line in the west London suburbs instead of at Euston mainline station; not extending the line north of Birmingham to Manchester; and pressing on with all, or some, of the project but at a slower pace, pushing its completion date back from 2033 to nearer to 2040.

What has the government said?

The chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, was the first to voice a denial of the story, which appeared in The Sun. He said that he couldn’t see “any conceivable circumstances” in which HS2 would not run to its planned central-London terminus at Euston, and added that he’d included the relevant funding in his autumn statement last year. However, it is not clear whether that funding was in some way inflation-proofed, and Hunt failed to say when the link to Euston would be completed.

Later on, Sunak gave a similar interview, but again didn’t volunteer any information about time frames. The prime minister also started talking about how HS2 shouldn’t get in the way of local rail upgrades “in the here and now”, suggesting that such a reordering of priorities is exactly what’s being discussed in government circles. Sunak may be looking for a more rapid political payback from transport projects, this close to the election.

What would happen if the route was snipped?

The project would go into a kind of downward spiral, and lose its point. Ending the line at Old Oak Common in west London would mean fewer platforms and thus fewer trains, fewer passengers and lower revenues – as well as being a less attractive prospect for passengers. Removing a strong passenger flow from Manchester, Lancashire and North Wales, via Crewe, would also harm its financial viability.

But hasn’t HS2 been troubled for some time?

It has been, almost from the moment it was invented in the dying days of the last Labour government, after which it was taken up enthusiastically by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. It was championed by the chancellor at the time, George Osborne, as part of a mission to revitalise the North and the Midlands, together with an enhanced East-West link across the Pennines. The intent was to offer a boost to both the Northern Powerhouse and the “Midlands Engine”. The HS2 legislation was passed in 2013.

At first it was a very ambitious project. The coalition ministers were like overgrown schoolkids with a giant Hornby set. The Y- shaped concept comprised two branches out of Birmingham. The North West route was to go via Manchester and then join up with the West Coast Main Line for Glasgow and far into Scotland. The North East branch would connect with the Midland Main Line and the East Midlands, and then go on to Leeds and Bradford, after which it would link to the East Coast Main Line and Newcastle. There was even a scheme whereby it would cross London in order to link to Heathrow and HS1, and thus enable connections to Paris, Brussels and Amsterdam.

Now, after successive reviews and cuts, only Manchester and the East Midlands spurs seem likely to survive. Probably.

What was the original point of HS2?

It was often derided as merely cutting a few minutes off a journey to London, but the real benefit was to be in increasing capacity on overcrowded routes, connecting and boosting isolated economies, and creating new, busier and enhanced commuter lines outside the South East.

What about the political benefits?

The original project would potentially have proved a substantial boost for the Conservatives. It would have proved their commitment to levelling up the regions, and made people in and around great cities such as Leeds, Bradford and Newcastle think more warmly of voting Tory. It would have helped the party to hold red-wall seats, even if the next election was years away. Now it has caused some considerable disappointment in Yorkshire and beyond.

And the political price?

In suburban and rural seats across the home counties and the West Midlands, there was and is much local opposition to the project, the potential effects of its implementation adding to more general concerns about the green belt and overdevelopment. Environmentalists have also raised objections relating to the loss of habitats and ancient woodlands. The loss of the safe Tory seat of Chesham and Amersham to the Liberal Democrats in a by-election last year was one example of an electoral backlash in the “blue wall”.

Some Tory backbenchers would rather the total cost of £150bn-plus be devoted to tax cuts or other public spending. Others favour the creation of a piece of strategic national infrastructure that will last for decades, if not centuries, like the Victorians’ railways and the Romans’ roads. Short-term political time horizons clash badly with long-term economic ones.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments