How could Britain take more effective action over Hong Kong?

There’s only so much a medium-sized power like the UK can do, but it can certainly do more than Raab’s passport offer, writes Sean O'Grady

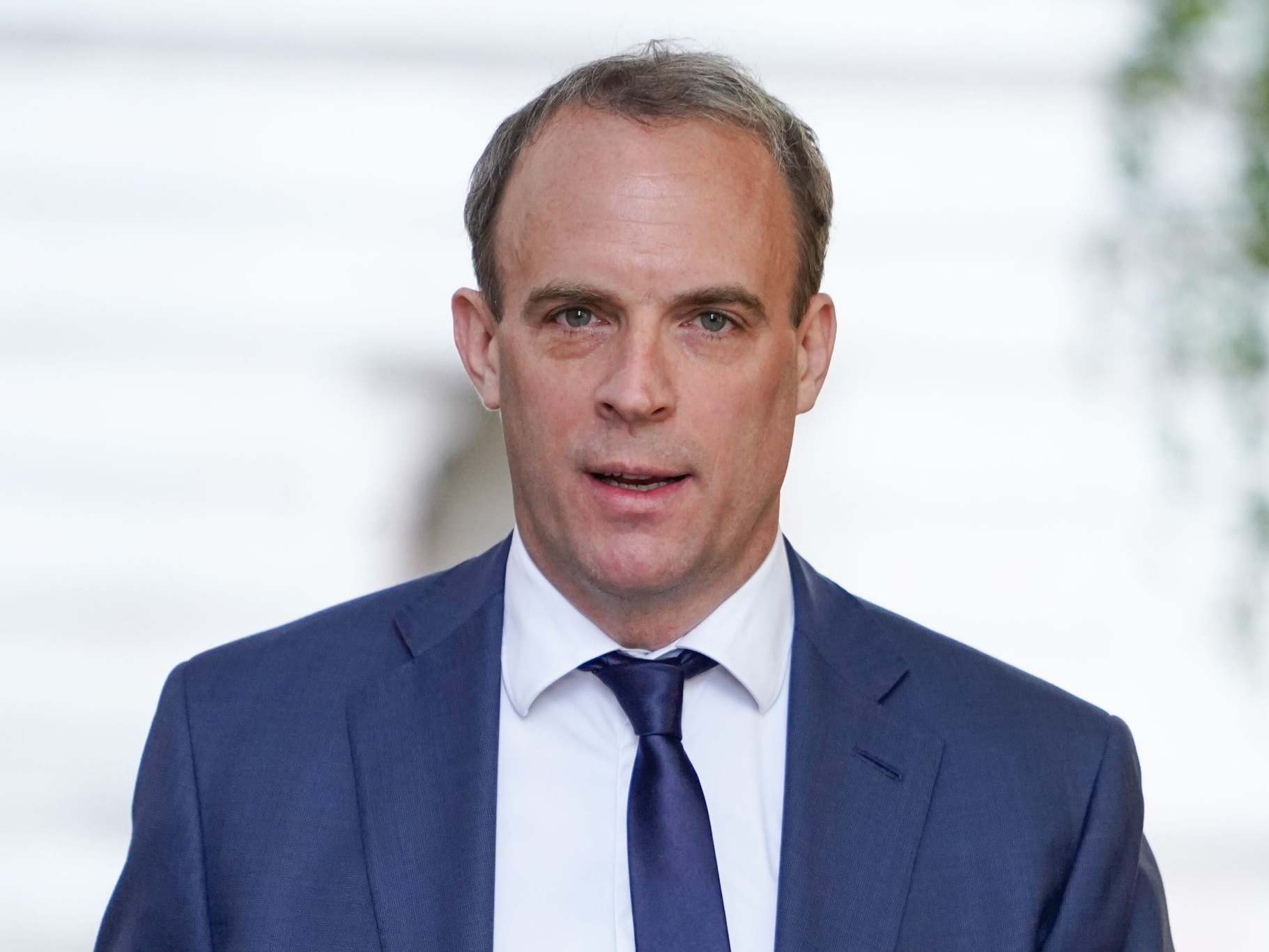

It is unusual for any foreign secretary to be, ever so diplomatically, monstered by a distinguished group of his predecessors. Yet such is the apparent weakness of Dominic Raab’s response to China’s power grab in Hong Kong that they could stay silent no longer.

So they have written a joint letter – an act which the coming generation may have to have explained to them as the pre-digital version of a Twitter pile-on – to his boss, Boris Johnson.

Spanning party lines and encompassing decades of experience, from David Owen (1977-79) to Jeremy Hunt (2018-2019), the former foreign secretaries feel that the government is not being energetic enough on Hong Kong.

They would like the UK to take the global lead on Hong Kong by setting up an international contact group, along the lines of that which the British led over the wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Britain is, after all, a co-signatory of the historic 1984 Sino-British declaration on Hong King. That internationally binding treaty guaranteed Hong Kong’s relatively free way of life from Beijing’s interference for 50 years. Now parts of it will be swept aside by a new security law for the autonomous region.

Mr Raab has been curiously quiescent in the circumstances. His most high-profile initiative has been to offer current holders of a so-called British National (Overseas) passport the right to come to the UK for good, rather than the six-month visits they are currently entitled to.

However that only applies to 300,000 Hong Kong citizens and Mr Raab suggests few would wish to settle in Britain in practice. Even if they did, it would hardly prevent a Chinese takeover of self-ruling Hong Kong. Mr Raab has instead tried to act with the US, Canada and Australia to persuade Xi Jinping to lay off Hong Kong, with no great effort to involve the EU for example.

For the moment, despite its legal, historic and moral obligations to the crown colony it handed back in 1997, Britain seems content to allow Donald Trump to lead the international campaign to keep Hong Kong free.

While the US certainly has the heft that Britain lacks, Mr Raab’s predecessors fear that Hong Kong will become embroiled in the US-China trade war, the row about the World Health Organisation and coronavirus, tensions about Tibet and Taiwan, and wider superpower rivalries, over, for example, nuclear weaponry and the (perceived) neo-colonial Belt and Road Initiative.

William Hague (foreign secretary from 2010 to 2014) has suggested that Britain is being too restrained: “We always talk about the British diplomatic service as a great Rolls-Royce. It hums along beautifully, keeping out of trouble. Now and again, we have to have the quick manoeuvre where the Rolls-Royce gets a bit scratched but the passengers get to the destination ... The French do not really hold back on coming up with a new initiative and presenting it to the rest of the world.”

Yet it is not entirely clear whether and how such a broad coalition assembled under UK leadership, as the ex-foreign secretaries suggest, would make much difference in reality. Britain is not the force it once was, and has suffered a long decline in power and prestige.

Britain long since handed over to America the lead role in the Middle East, parts of Africa (notably Zimbabwe) and East Asia it once enjoyed. Meanwhile China has, on some measures, grown to be the world’s largest economy, responsible for a quarter of planet’s manufactures, with a population 20 times larger than Britain and four times greater than America. It is more assertive, too.

As a permanent member, China can, as it did only a few weeks ago, veto any discussion of Hong Kong at the UN Security Council. The EU and America are also divided about the right response. While, for example, Australia, Sweden and the US are open to imposing sanctions on China, or enduring Chinese sanctions on them, other players are more reluctant to lose Chinese investment and sacrifice useful markets.

Yet even in this context the UK has displayed some uncertainty of purpose. The Johnson government, unlike the one run by David Cameron and George Osborne, has no great vision of a “golden age” of British-Chinese relations, and has sometimes struck a half-sceptical note about the involvement of Huawei in the 5G programme.

Covid-19 has dampened enthusiasm for global supply chains originating in the People’s Republic. Yet the UK, post-Brexit, needs a strong economic relationship with China. As a former Brexit secretary perhaps Mr Raab understands that better than most.

Yet the rising wave of Sino-scepticism in the Conservative Party threatens to replace the old Euroscepticism as an obsession, leaving the US and Japan as Global Britain’s remaining hopes for international influence and prosperity. Neither are sure-fire bets.

As Mr Raab approaches his first anniversary as foreign secretary in July, he should take the opportunity to set out his vision for what a medium-sized economy such as Britain realistically can and cannot do in foreign policy, especially when it tries to size up to a bully the size of China. Otherwise he should just leave the Rolls-Royce in the garage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments