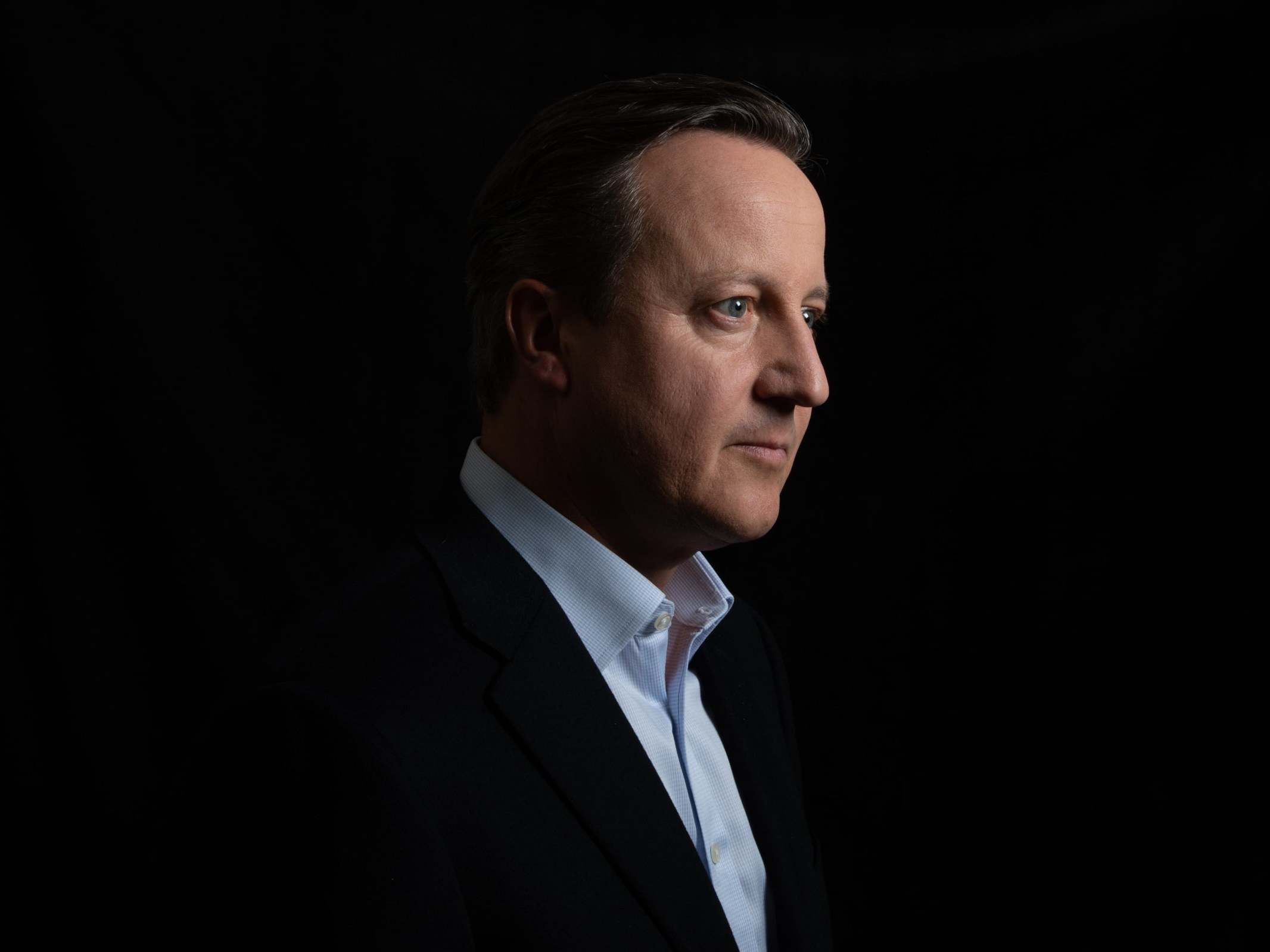

Like David Cameron with Boris Johnson, other former PMs haven’t been able to keep quiet on successors

The blue-on-blue attacks over Brexit may feel unprecedented but, writes Sean O'Grady, there’s a rich history of ex-premiers making life difficult for those who come after them

Like comedy and sex, the key to success in publishing is timing. For David Cameron, his memoirs look perfectly scheduled: just before the Tory conference, in the last days before Brexit (or not) and when those who betrayed him and the country are now running the government – Boris Johnson and Michael Gove. A good time to bury bad people, you might say.

It is fair to say, however, that Cameron was probably aiming to get his side of the story out before now, and after Brexit had happened, but as we know it keeps getting postponed. Even so, the damage inflicted on Gove and Johnson is real enough and sincerely meant by Cameron, and it fits into a general publicly accepted narrative about the pair of them being pretty dodgy, and given to stabbing one another in the front or the back as the occasion demands – “ambassadors for the expert-trashing, truth-twisting age of populism”. So now it is Cameron’s turn, and the character assassinations are executed with exquisite precision.

Yet none of this is unprecedented, dramatic as it may be, and it may not matter much. In a sort of cycle of abuse, most prime ministers suffer from criticism from their predecessors and then, in time, visit the same persecution on those who come after them. Exceptions, in modern times, are rare: even when Cameron said that he felt “desperately sorry” for Theresa May, it sounded more condescending than supportive.

The last Conservative prime minister before Cameron, John Major, was subjected to a notorious campaign to undermine him by his predecessor, Margaret Thatcher. Then, as now, the central issue was Europe, and, as a former Tory prime minister of record-breaking standing and deified by her party, she could make lots of trouble. Young backbenchers in the 1990s – Thatcher’s political children – turned to her for advice about the Maastricht treaty debates, and she sometimes joined them and even voted against her own party. The Eurosceptic rebels of then are the mainstream of the party today. Major though tormented by his “back seat driver” never thought to remove the whip from her, and only voiced his frustration at the “bastards” faction she effectively led in code or inadvertently. He was mostly dignified. For her part, Thatcher remained unreconciled to the internal cabinet coup that removed her from power in 1990 – “treachery with a smile on its face” as she memorably put it, a metaphorical tear in her eye.

It is no surprise then that Cameron and Major should now be doing the same to their latest successor, Johnson, a man who was never notably supportive of either prime minister. Indeed, Major took the novel step of taking Johnson to court. Maybe Johnson will one day do the same to a Tory successor, if there ever is one. Now it is Major’s turn to play the “bastard”.

Just as Thatcher was ignored by Major, so Johnson will ignore Cameron

And just as she sniped at Major, so Thatcher too was attacked by two of her distinguished one-nation Tory predecessors. Ted Heath, who had appointed Thatcher to his cabinet only to be later toppled by her in 1975, never ceased to oppose her economic policies, not least because they were a repudiation of his. He attacked her policies from the floor of the 1981 Tory conference. Her famous quip about “you turn if you want to, the lady’s not for turning” was a play on the political U-turns that Heath was famous for. Later on, Heath and Thatcher commanded rival battalions in the Tories’ civil war over the EU. He said she had a “tiny mind”, which was a bit small-minded of him.

More damaging, because they could not be put down to personal animosity, were the appeals made by the elderly Harold Macmillan – successful architect of Tory ascendancy in the 1950s. He spoke, aged 90, his voice cracking, during the bitter miners’ strike of 1984-85 in these terms: “It breaks my heart to see – and I cannot interfere – what is happening in our country today. This terrible strike, by the best men in the world, who beat the Kaiser’s and Hitler’s armies and never gave in. It is pointless and we cannot afford that kind of thing.

“Then there is the growing division of comparative prosperity in the south and an ailing north and Midlands. We used to have battles and rows, but they were quarrels. Now there is a new kind of wicked hatred that has been brought in by different kinds of people.”

More satirically, he compared privatisation to a skint aristocratic family: “First of all the Georgian silver goes, and then all that nice furniture that used to be in the saloon. Then the Canalettos go...”

Neither elder statesman did much to change Thatcher’s mind, though, just as she was ignored by Major, and Johnson will ignore Cameron and Major.

Nor were Tony Blair’s much-rumoured doubts about his Labour successor Brown of the greatest concern during the latter’s turbulent premiership. By the time Tony Blair got around to publishing his memoirs, and telling us that he had wanted to sack Gordon Brown as his “maddening” chancellor, it was all too late anyway, and Brown had already been ejected from No 10 by the voters. When Blair had become premier in 1997, all of his Labour predecessors had died, except for James Callaghan, who beamed with satisfaction on election night, 18 years on from his own defeat by Mrs Thatcher. He passed away in 2005. Indeed, Blair and New Labour also mostly enjoyed favourable reviews from the likes of Thatcher and Heath, much to the chagrin of the Tory leadership of the time. Today, of course, Blair’s commentaries are always overshadowed by Iraq.

What is interesting is that the one single ex-prime ministerial intervention that had a demonstrable impact on events was Brown’s powerful appeal for the Union in the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence. It was utterly devoid of personal animus, had nothing to do with internal party battles, and was an act of statesmanship. The polls had narrowed to virtually neck and neck. Brown moved them back towards the Union. It is not going too far to say that Brown, armed with a concrete counter-proposal to independence, saved the United Kingdom: “The choice is now between irreversible separation, or voting for a stronger Scottish parliament… this is a referendum for 50 to 100 years ahead. We are not making a decision about ourselves. We are making a decision for the children of Scotland.” It was Brown at his best. Given also his role in saving the financial system in the 2008 crisis, maybe his place in history looks rather better than that of the man who replaced him.

Still, Brown in 2014 is the exception. For the most part, yesterday’s men and women, then, can command the headlines, distract and annoy those who took over from them, and you’d anyway expect them to offer the benefit of their experience. So they should. They can be wise and shrewd, and entertainingly acerbic. As part of the soap opera of politics, they are essential players, and they usually cannot help themselves from going just a bit too far. Yet they are still ghosts in the machine, a chilling presence, but quite unable to pull the levers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments