Coronavirus: The WHO is not perfect, but it needs everyone’s support

The body is only as strong as its member states, writes Sean O'Grady

A global public health crisis needs a global strategy, it has been said often in recent weeks, and for obvious reasons. That being so, the principal international agency concerned with such matters might be expected to play a central, leading role in the effort to contain the coronavirus. Yet the World Health Organisation has been ignored and derided in equal and considerable measure, just at the moment when it could be vindicated. Its central mission is as crucial as at any time in its 72-year history; yet it is floundering.

The most trenchant criticism has come from President Trump. In recent days he has threatened to cut America’s funding for the WHO (the US is the largest single donor), accused it of failing to learn about the pandemic early enough, and generally being too “China-centric”. Such criticisms from the right of politics throughout the west may be expected to intensify as the crisis continues to worsen.

Part of that is down to Trump’s usual habit of laying the blame for misfortunes and errors in America’s own response at the door of some foreign entity. The WHO, an agency of the United Nations, is a small but high profile and highly convenient scapegoat for the rising toll of deaths in the US. So, of course, is China as with the attempt to rename the coronavirus the “China virus“. The WHO have attacked the president for trying to “politicise” the pandemic.

In fairness to Trump, he has a point. What success the Chinese authorities may have had with their lockdowns, in the early stages of the epidemic they tended to play down the threat, and in particular the extent of person-to-person contagion. The coronavirus undoubtedly emerged from an unsanitary so-called “wet market” in Wuhan, and some doctors who tried to raise the alarm were discouraged from doing so.

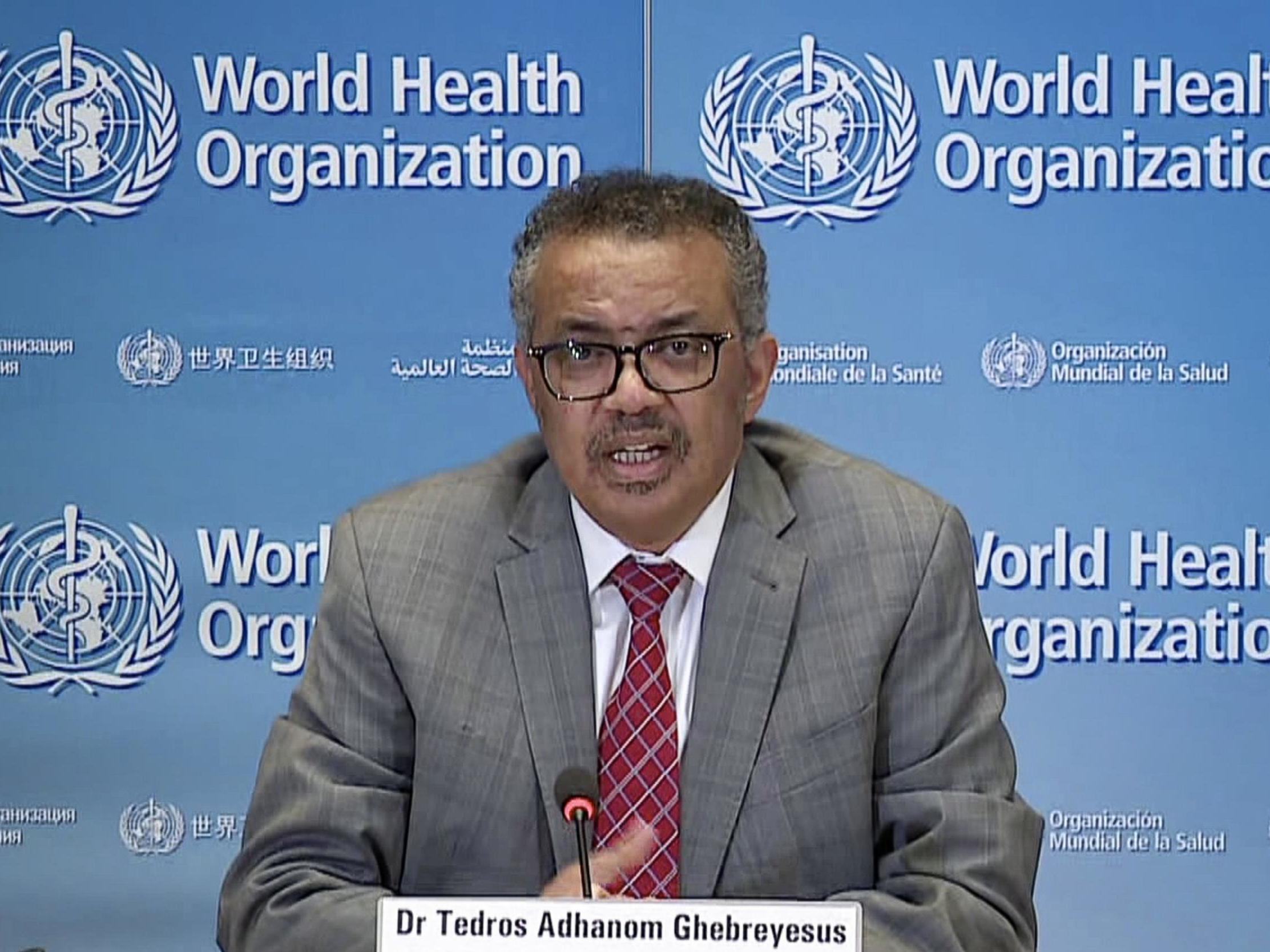

Throughout this episode the WHO has made little criticism of China and is now under intense pressure to speak out against those “wet markets”. The director-general of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreysus, is a former health minister of Ethiopia, and was China’s nominee for the job – the two nations have been growing closer economically. He has praised China’s “extraordinary” efforts and the WHO stated on 14 January: “Preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus identified in Wuhan, China.” Only a few days later China admitted how contagious it really was. An effort by a journalist to raise Taiwanese concerns at the WHO press conference was ignored by officials there. The very existence of Taiwan as a state is resented by China, which claims sovereignty over it. One member of the WHO emergency committee has condemned China’s “reprehensible” response – a lone voice.

Still, from a British and American perspective, the WHO has probably been more right than wrong about the importance of monitoring the disease. Three weeks ago Ghebreysus was urging governments to “test, test, test”, an approach that seems to have enjoyed success in Germany and South Korea. The WHO, for all its faults, remains the only relevant global agency, and, as Covid-19 spreads to poor developing countries, is one of the few organisations in a position to help countries such as the Central African Republic which has access to three ventilators for a population of four million.

If, or when, Covid-19 establishes itself in large population centres in the developing world, it cannot be contained there and prevented from reappearing in the richer countries. There is no wall or heavily policed political border that can resist the coronavirus. Trying to save lives in the developing world, indeed in places such as Ghebreysus’s Ethiopia, will be the next great task confronting the WHO and aid agencies such as the International Rescue Committee. The WHO has enjoyed historic successes against smallpox and Ebola but, like any international body, it is only as strong as its member states make it. Without the support and funding of the rich nations, the prognosis for defeating Covid-19 is poor.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments