Do conference speeches really matter?

Voters preferred Starmer’s address to Boris Johnson’s, a new poll has found – but does anyone care, ponders Sean O’Grady

According to some novel research, voters think Sir Keir Starmer came across more competent, in touch and agreeable in his conference speech than Boris Johnson did in his shorter and, by most accounts, wittier oration. The pollsters at Opinium showed 1,305 voters highlights from the two performances, as if they were contestants on The X Factor. The results were mixed, shall we say. The researchers found that more voters agreed with Johnson than disagreed and more felt he was strong, caring and competent than not.

But politics is a competitive game, and he needed to shade his rival, and here the prime minister was less successful. His scores were less favourable than those for Starmer’s speech in Brighton, even though the Labour leader was continually heckled, while Johnson was only interrupted by giggles from “Jon Bon Govey”, among many others at the Trump-style rally.

Should anyone take any notice? Do speeches matter? It’s the way of the jaded journalist to dismiss them as just so much candyfloss, useful source material at best, badly written and clumsily delivered propaganda at worst. Most of them actually are, but, even just sticking to the British contribution and leaving aside the likes of Hitler or Martin Luther King, it’s plain that a skilled orator can galvanise a nation. Winston Churchill, so the historians agree, did at least see good with his wartime addresses to the Commons and the nation, while Hitler’s disappearance from the airwaves as the tide turned against him damaged the morale of Germany.

In peacetime too, some conference speeches are recalled decades after. They seem to work best when an artful phrase or defiant declaration fits elegantly into a wider set of political messages. When, for example, Margaret Thatcher told her party conference in 1980 that “the lady’s not for turning” during a deep recession, her point was that she wasn’t going to U-turn on her tough, monetarist anti-union policies, and indeed, for the most part, she did not. Similar defiance was showed by Hugh Gaitskell, whose reputation for bravery, and stubbornness, was enhanced when he told his critics he would “fight, and fight again to save the party we love” from the unilateral nuclear disarmers, and he too was as good as his word. So was Neil Kinnock when he condemned the Militant tendency in 1985, Derek Hatton yelling at him as he did so from the floor. There were distant echoes of his predecessors’ travails when Starmer told his party they had a choice between “slogans or changing lives”. The “white heat” modernism of Harold Wilson in 1963 caught a modernising mood of that newish) decade, just as did Tony Blair’s chanting of “New Labour, new Britain” thirty years after. There’s even a hint of it in Johnson’s equally facile “Build Back Better”.

On the other side, a poor speech badly delivered can feed a less helpful narrative. When things started to badly wrong for John Major in the 1990s, his critics chose to focus on his flat, nasal delivery of such initiatives as the “cones hotline” as symbolic of the wider failure; it contrasted badly with his rival Michael “Tarzan” Heseltine’s ability to bring a dozing audience of aged Tories to shuddering crescendo. Enoch Powell had an even more compelling demagogic style. So did Michael Foot, a man of rare literacy. Tony Benn’s parallel ability to make a Labour audience believe that socialist victory was at hand also took him a long way in his party – though none of Powell, Foot, Hezza or the Bennatollah ever quite got to the very top.

The impression that Labour was careless about the economy and the public finances was unfortunately reinforced when journalists at the 2014 Labour conference realised that the leader had forgotten to mention the economy (stupid). Miliband was following the fashion, pioneered by Ann Widdecombe some years before, of extemporising and doing without an autocue. Leaders tend to stick to the script these days.

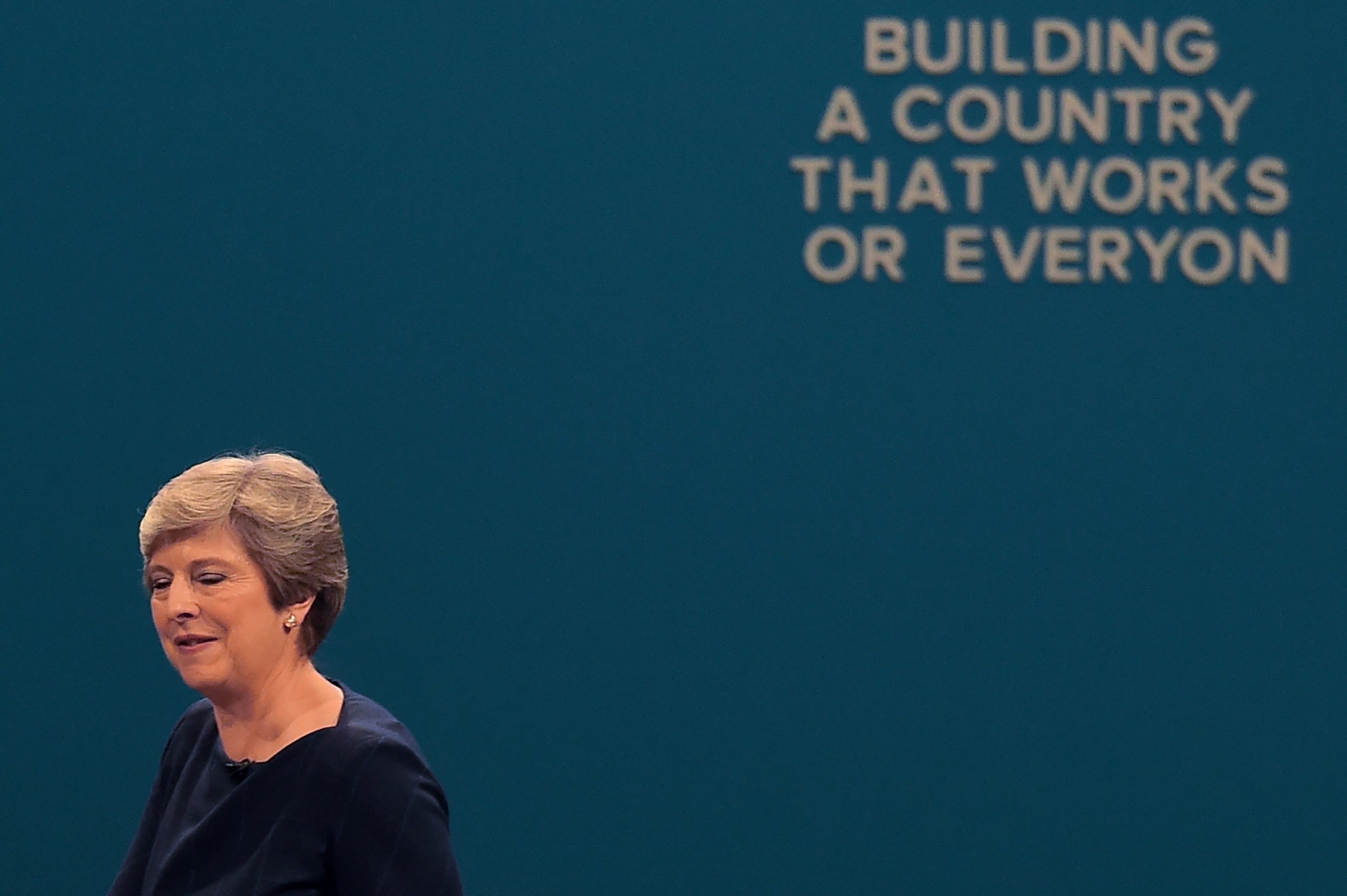

But the speech in recent years that did the most damage to any politician of any party was the one that befell Theresa May in 2017. Even her worst enemies (most of whom were in the hall) felt sorry for her as she croaked, coughed and stumbled her way through a speech, interrupted as well by bits of the slogan on the backdrop falling off, and a prankster handing her her P45. She’d not long since lost her majority in the disastrous 2017 snap election, one in which Jeremy Corbyn, 20 points behind in the polls when it started, proved to be a remarkably good speaker out on the stump and almost became prime minister. People, especially in her own party, took the view after her near election defeat and her omnishambolic speech that May was unlucky, had an awkward way about her, and was a poor campaigner, and they were right. She didn’t last that much longer.

Now having seen their first proper public speechmaking in two years, Boris Johnson can’t be trusted though they agree with him, and Starmer knows what he’s doing but they still won’t vote for him. What can one say?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments