Five Budgets that left their mark on history – for good and bad

Some chancellors made a mark on politics, perhaps in ways they never intended, as Sean O’Grady explains

It remains to be seen if Jeremy Hunt’s last spring Budget before the election makes much impact on his party’s chances of winning a fifth term. In truth, Budgets tend to be ephemeral things with measures reversed by successive administrations – or even by the same chancellor. However, a few Budgets did leave their mark on history, for good and bad reasons…

1981: Geoffrey Howe

This Budget, coupled with a very tough spending settlement in the 1981 autumn statement, marked an ideological as well as political break with post-war traditions. Despite some moves in this direction during the previous Labour government, this was the first truly monetarist budget, placing money supply and targets for public borrowing and inflation ahead of considerations about unemployment. Previously, almost every government of both parties since the Second World War believed that achieving very low joblessness – “full employment” – was the overriding aim of government policy, even if it was getting more difficult to achieve amid bouts of inflation and price and wage controls that broke down.

Howe, later to become Lord Howe, produced a Budget in the middle of what was then the worst recession since 1945, and it produced uproar. Rather than borrowing to stimulate industry and get Britons back to work, Howe raised taxation – by freezing thresholds, funnily enough – and unveiled further cuts to public spending. The shock treatment to the economy finally broke the wage-price spiral but pushed unemployment towards three million. It split the cabinet and the Conservative Party, but Howe and his prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, prevailed. It was followed up by a new cash-limited approach to departmental spending. The squeeze on inflation in the 1981 Budget allowed for a rise in living standards for those in work, and helped deliver a record Tory landslide at the 1983 general election. It also changed the terms of political debate.

1992: Norman Lamont

After a fairly nasty recession, John Major’s administration was still behind in the polls as the end of its parliamentary term loomed. A widespread assumption was that Neil Kinnock’s Labour would form an administration, possibly in a hung parliament, at a general election that could not be long delayed. Chancellor Lamont pulled off a considerable coup in his March 1992 Budget with an unexpected new basic income tax rate of 20p in the pound. In truth, it was only a new threshold, set very low, on the first £2,000 of income, but it was a headline-grabber.

However superficial it was, Kinnock had no ready answer to the move, which allowed the Tories to fight the general election one month later by saying Labour was planning to raise income tax and VAT (both largely fictional claims). Major won with a narrow majority but by September, the ERM crisis had shredded the party’s reputation for economic competence. The irony was that, by then, the Conservatives had managed to set Britain on a path of steady growth, rising employment and living standards and sustainably low inflation. For that, they received no thanks.

2007: Gordon Brown

In his last Budget as chancellor, Brown hoped to end his decade-long stewardship of the public finances with a flourish, emulating Lamont’s dramatic move in 1992. Brown decided to enact what had been a New Labour ambition since 1997 and introduce a new 10p band of income tax. It certainly attracted attention and reinforced his aura as a fiscal genius (Tony Blair called him the best chancellor in history).

However, it soon transpired that some taxpayers would end up worse off because of complexities in the tax system and, by the time he became prime minister later the same year, further measures had to be introduced to mitigate the impact. The episode took the shine off Brown’s reputation, introducing an early element of fallibility that eventually led to his 2010 general election defeat.

2012: George Osborne

As the first Tory chancellor in more than a decade (albeit as part of the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition), and at the unusually young age of 39, Osborne was tasked with reducing the national deficit which had ballooned during the bank bailouts. This was achieved through an infamous programme of austerity in which public spending bore the brunt of the task. Osborne also established the Office for Budget Responsibility, which has proved a lasting success as an independent watchdog.

Arguably, Osborne got some of the bigger calls right in his time but a series of botched tax adjustments gave rise to the fiscal event for which he will be most remembered: the 2012 “Omnishambles” Budget. Complex and otherwise trivial changes to VAT rates including on “ambient hot food” (the so-called “pasty tax”) became mired in increasingly absurd arguments. As Osborne himself admits: “I did eight Budgets, and [2012] was the one that properly unravelled.”

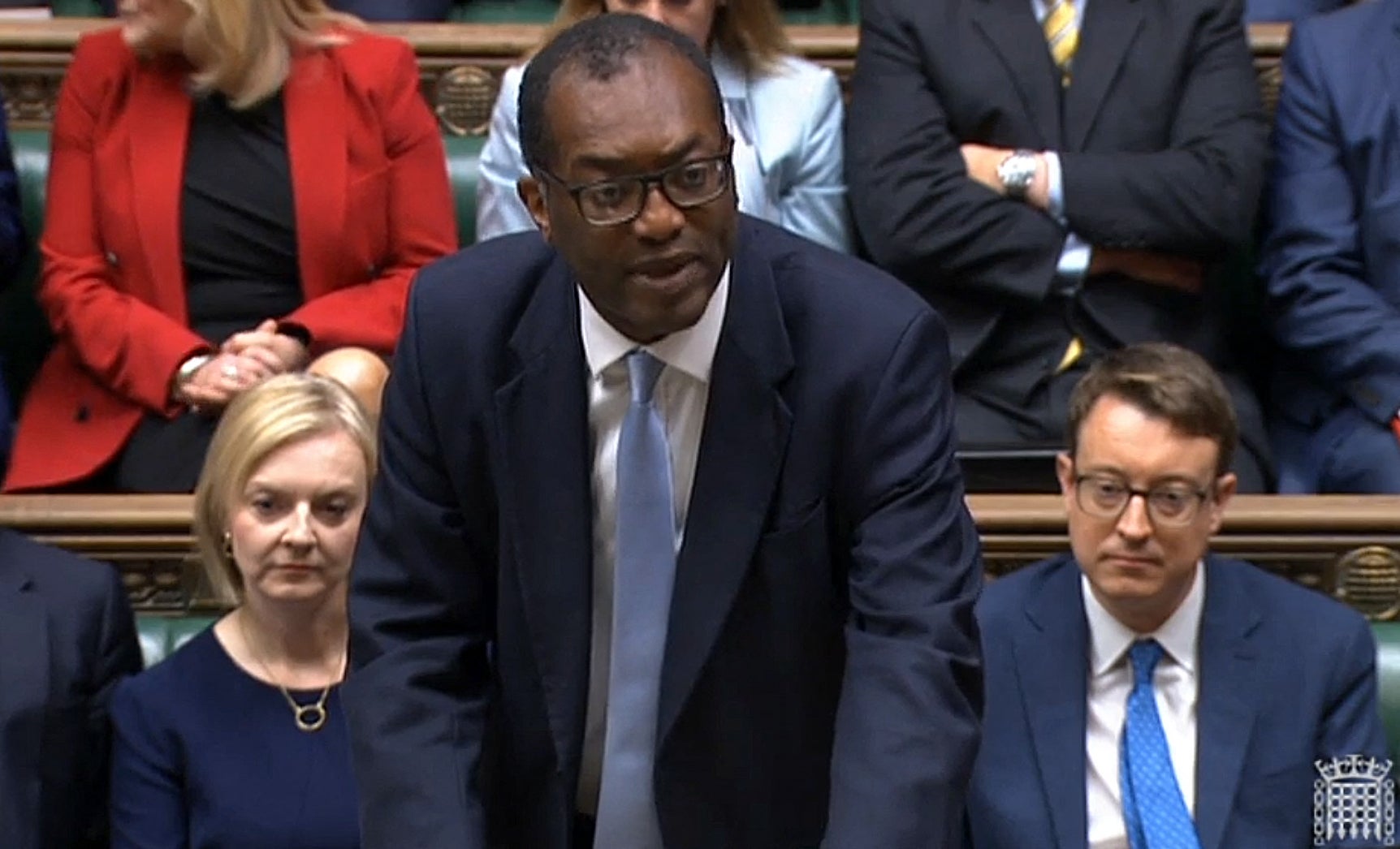

2022: Kwasi Kwarteng

It was a mini-Budget that caused maxi trouble for the short-lived premiership of Liz Truss and her old friend and new chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng. In its way, it was a brave attempt to try and jolt Britain into higher economic growth, which was rightly seen as the cure to many of the nation’s difficulties. But the new government foolishly decided to exclude the OBR and the Bank of England from its preparations, going for costly and high-profile tax cuts combined with a pledge to maintain public spending.

Such unfunded tax cuts implied higher borrowing, and the lack of any independent official assessment of their impact sparked panic in the financial markets, a run on sterling and the near-collapse of the pensions sector. The Conservatives’ poll ratings collapsed just as precipitously and, after 49 days in office, Truss was out (having already jettisoned the hapless Kwarteng during his return from an awkward IMF conference in Washington). Once again the Conservatives’ reputation for economic competence was shattered.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments