Boris Johnson’s trade talk shows Brexit is not a done deal

Not for the first time, the prime minister’s words may come back to haunt him, writes Sean O'Grady

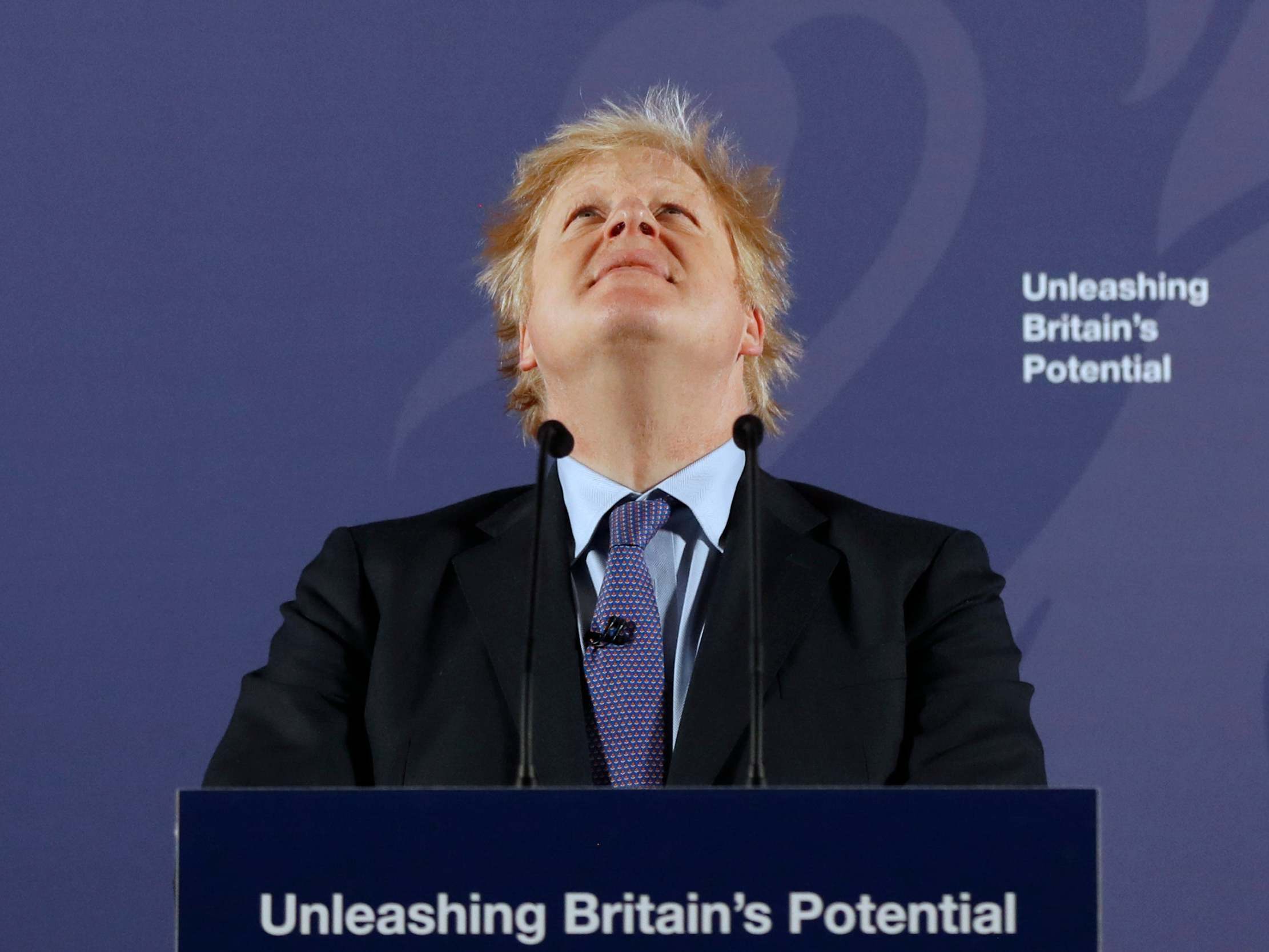

The prime minister is well known for eschewing detail and travelling light when approaching policy dilemmas. So light, in fact, that he ties to glide over them.

Even so, his landmark speech at Greenwich on the future of British international trade was exceptionally sparse. Approaching a half of British exports go to the European Union, as of now, and millions of jobs depend on what new arrangements will take the place of the single market and the customs union, which have operated for nearly 30 and 50 years respectively.

Yet all Boris Johnson had to say in specifics – leaving aside his references to the glories of Britain’s maritime past – was: “The question is whether we agree a trading relationship with the EU comparable to Canada’s – or more like Australia’s. And I have no doubt that in either case the UK will prosper.”

There is, in fact, a substantial difference between these casually presented two options. The Canadian option is one which sees a much more liberal trading relationship than is usual between the EU and an external partner.

The Australian option is not much more than a declaration of aspiration across a broad range of political and economic fields, including, for example, working together on the development of Papua New Guinea. It is basically an agreement to work through the World Trade Organisation for a multilateral global reduction of barrier to trade – rather a forlorn hope. In other words, the European Union-Australia Partnership Framework of 2008 is a collection of aspirations. It is not free trade agreement, or a treaty, or legally binding, or anything like it. If transposed to the UK, it would mean the hardest of hard Brexits.

There are talks now between Australia and the EU for a free trade deal, one that might mirror those concluded with South Korea and Japan for example, but far less comprehensive than the Canadian one. The EU-Australia free trade remains in the future, and it is not what Mr Johnson was, probably, referring to.

The Canadian example by contrast sees the abolition of almost all of both sides’ tariffs and quotas on imports, as well as access to certain service markets, intellectual copyright protections and mutual recognition of certain product standards and professional qualifications.

Canada or Australia options? There is, as the expression goes, a world of difference between the two.

Since the 2016 referendum, the UK and the EU have openly discussed the attractions of a “Canada-style” agreement. With additional clauses on security, data exchange, travel, student and academic programmes, and foreign policy, this was sometimes termed “Canada+++” to signify its bonus features.

However, the UK-EU Withdrawal Treaty, agreed last October between the Johnson government for the UK, and the European Union, makes clear that a “Canada-style” or “Canada +++” the abolition of almost all tariffs and quotas, will only be implemented provided, in the famous phrase, there is a “level playing field” between the two parties: “The parties agree to develop an ambitious, wide-ranging and balanced economic partnership. This partnership will be comprehensive, encompassing a Free Trade Agreement, as well as wider sectoral cooperation where it is in the mutual interest of both parties. It will be underpinned by provisions ensuring a level playing field for open and fair competition”.

The “level playing field” is further defined thus: “The parties should uphold the common high standards applicable in the Union and the United Kingdom at the end of the transition period in the areas of state aid, competition, social and employment 15 standards, environment, climate change, and relevant tax matters.”

“The parties should in particular maintain a robust and comprehensive framework for competition and state aid control that prevents undue distortion of trade and competition; commit to the principles of good governance in the area of taxation and to the curbing of harmful tax practices; and maintain environmental, social and employment standards at the current high levels provided by the existing common standards. In so doing, they should rely on appropriate and relevant Union and international standards, and include appropriate mechanisms to ensure effective implementation domestically, enforcement and dispute settlement.”

It is this that both sides are now finding it difficult to map out. The British government now rejects any ongoing legally binding treaty-based commitment to maintain EU standards as defined by the EU. This is because it would leave the UK as a “rule taker” and, in the eyes of the government, negate the entire point of Brexit, which was to allow the UK to design its own laws and institutions to suit its internal needs and serve its external interests best – including being able to compete in world markets for goods and services.

The conundrum is that the UK says it would in any case have standards in many areas as high as the EU, if not higher. In his speech Mr Johnson mentioned animal welfare (live transport of livestock) and paternity rights to offer up a couple of examples where Britain would like to or has already enhanced EU standards. However, the principle being enacted is that such activities are entirely a matter other British government, parliament and people, and not subject to EU approval or control. Some may be identical to the EU; others equivalent, but different; others more divergent.

The EU, on the other hand, sees the emergence of the UK as a potentially dangerous competitor on its own doorstep. The German chancellor Angela Merkel has spoken of the economic threat to the EU, one that would be markedly more potent if the UK decided to alter its regulations to reduce costs, improve efficiency and win a competitive edge – which Europe might see as an unfair advantage. In the context of reforming the EU, Merkel said: “We will do all this in the knowledge that with the departure of Great Britain, a potential competitor will of course emerge for us. That is to say, in addition to China and the United States of America, there will be Great Britain as well.”

European officials consistently argue that Britain must commit to a level playing field on issues such state aid, labour rights and environmental protections (as Canada has with the EU) if the UK wants to enjoy tariff free and other free access to EU markets.

There is one last literally divisive point. At the moment, the withdrawal treaty places Northern Ireland under a different economic regime to the rest of the UK – inside the EU customs union and parts of the EU single market. If the UK (for the sake of argument) agreed to a “Canada +++” trading and economic relationship with the EU, then the new economic barrier between Northern Ireland and Great Britain would indeed be a fairly lightly policed one. If, though, the UK ended up on WTO terms with the EU – the so-called Australian model – then that would entail a far harder border between two parts of the United Kingdom, because Europe would need to impose many more regulatory checks to protect the integrity of its single market (and because it is mutually agreed to have no checks or other apparatus on the Ireland/EU-Northern Ireland frontier. That, if you recall was an issue Mr Johnson once resigned from Theresa May’s government over. He said soon afterwards, at the 2018 DUP Conference:

“If we wanted to do free trade deals, if we wanted to cut tariffs or vary our regulation then we would have to leave Northern Ireland behind as an economic semi-colony of the EU and we would be damaging the fabric of the Union with regulatory checks and even customs controls between GB and NI – on top of those extra regulatory checks down the Irish Sea that are already envisaged in the withdrawal agreement. No British Conservative government could or should sign up to anything of the kind.”

Those words may yet rerun to plague him; it is impossible to see many of his own MPs, big majority or not, accosting an internal British economic frontier. If Mr Johnson attempted to evade the legal responsibilities of the withdrawal treaty, Brussels would take international legal action, and meantime impose a new hard border on the Ireland-Northern Ireland border.

There would also be some parallel complexities surrounding the Gibraltar/Spain crossing – anther highly sensitive issue. Remember too, that every relevant regional and national parliament in the EU (about 30 in all) will have to ratify any new UK-EU trade deal – and that the process is supposed to be complete (under British law) by midnight on 31 December. The Spanish and Irish parliaments might have something to say about the borders; and the French and Danes something to push back on over fisheries, while the European parliament remains restive about EU citizens’ rights in the UK. All have a veto.

Conclusion: Brexit is not a done deal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments