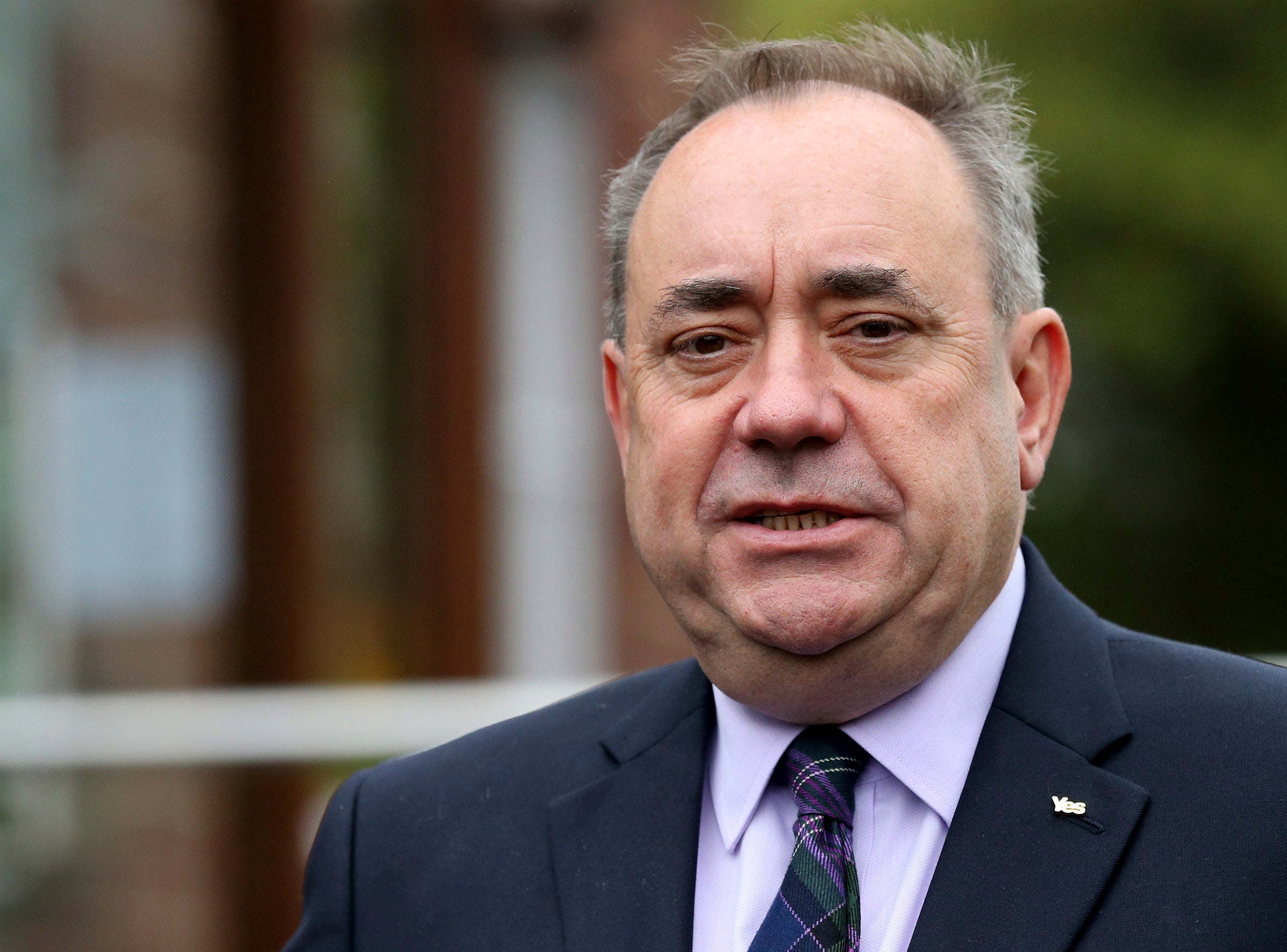

What Alex Salmond’s political return means for Scottish independence – and for Nicola Sturgeon

Sean O’Grady explains why the first minister has reasons to be cheerful and fearful about the new Alba Party

On social media there’s a good deal of debate about the correct pronunciation of “Alba”, as in “Alba Party”. Alba, being the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland, is not spoken as “AL-BA” but rather as (almost) “ALaBPA”, a softness and micro-gap between the two syllables.

Of course, given the personality of its de facto leader, the “Alba Party” should probably be more correctly called the “Alex Party”, because Alex Salmond, former leader of the SNP and now famously estranged from it, will no doubt dominate it. It is not quite a vehicle for his outsized ego, but there’s not that much room for anything else.

Apart from relaunching the political career of Mr Salmond, what is the Alba Party for? The party itself describes its aim as creating a “super majority” for Scottish independence in the Holyrood parliament after the elections on 6 May. Apart from that: “The party's strategic aims are clear and unambiguous – to achieve a successful, socially just and environmentally responsible independent country ... We intend to contribute policy ideas to assist Scotland’s economic recovery and to help build an independence platform to face the new political realities.”

Puzzled onlookers might point out that Scotland already has a party committed to such things – the Scottish National Party, formerly led by Mr Salmond and, since the loss of the first referendum on independence in 2014, by Nicola Sturgeon. The party has been in power since 2007, and looks set to win the election in May once again.

Read more:

Yet the majority, if any, that the SNP seems likely to win also seems likely to be slim, because Scotland’s electoral system is designed to prevent Westminster-style landslides. Mr Salmond’s argument is that a very large majority in the parliament is required to strengthen Scotland’s legal and moral case for another referendum, and in due course the restoration of Scotland’s sovereignty. He appears to believe that Alba can offer a “Heineken Effect” – reaching pro-independence voters that the SNP, under his leadership and that of Ms Sturgeon, cannot reach. That does seem to be stretching a point, but there’s no doubt that he has a personal following, charisma, and will almost certainly get a list seat under the system of proportional representation. His party will not contest SNP constituency seats, and should not split the nationalist vote. What he can and will do is divide the nationalist cause.

Independence is for Mr Salmond an “immediate necessity” and “overwhelming priority”. Mr Salmond seems to believe that other issues, such as even the pandemic, the economy and education cannot be properly solved unless Scotland can govern itself properly. There is some impatience with the cautious approach to securing independence being pursued by Ms Sturgeon. She has stressed that any referendum should be “lawful” which means that it has to be approved by the Westminster parliament – in effect by Boris Johnson. That is unlikely to be forthcoming. With support for independence around the 50 to 60 per cent range victory cannot be taken for granted in any case. The SNP has slightly dialled down the rhetoric on independence recently, though it has also hedged its bets by publishing a bill for an independence referendum that would, perhaps, be held if Mr Johnson refused to grant one and, frankly, the independence cause looked like winning.

Mr Salmond’s party is more radical, impatient and insistent on the referendum and on independence, and he reflects a strand of opinion in Scotland (and indeed within the SNP) that questions whether the “Section 30 route”, after the relevant section of the 1998 Scotland Act, is necessarily the only path to freedom. Joanna Cherry QC, for example, the SNP MP who took the UK government to court over Brexit and propagation, argues that the example of Ireland a century ago is instructive and provides a powerful constitutional precedent. When in the election of 1918 the Irish nationalists (Sinn Fein) won a landslide majority of Irish seats and almost every seat in southern Ireland, at a time when Ireland was still entirely in the UK, it was taken as a mandate for immediate independence, without even a referendum.

As Ms Cherry explains it: “One hundred years ago, Irish independence came about not as a result of a referendum but as a result of a treaty negotiated between Irish parliamentarians and the British government after nationalist MPs had won the majority of Irish seats in the 1918 general election and withdrawn to form a provisional government in Dublin.

“While no one wants to replicate the violence that preceded those negotiations, the [Anglo-Irish] Treaty is in legal and constitutional terms a clear precedent which shows that a constituent part of the UK can leave and become independent by a process of negotiation after a majority of pro-independence MPs win an election in that constituent part.”

Mr Salmond’s appeal for a “super-majority” at Holyrood suggests a similar logic and strategy in making his claim for right for freedom. What followed in Ireland – partition and civil war – isn’t such an attractive prospect, but the lesson of history about a nation’s de facto and arguably de jure right to sovereignty stands. Events in Catalonia also suggest that attempts to go it alone on the back of what critics will deride as a glorified opinion is hazardous. The Supreme Court might be asked to intervene to clarify whether, say, an unofficial referendum held by the Scottish government had or would have any validity.

Read more:

The most extreme version of this might involve peaceful demonstrations for a referendum or peaceful civil disobedience and/or a policy of non-cooperation with the UK authorities by the Scottish government (maybe unwise in a pandemic). Again, this is pure speculation about where the Alba Party may end up – but it is logical if the party sees independence as the overwhelming priority.

At any given point, it seems likely that Mr Salmond will be pushing Ms Sturgeon to go further than she seems inclined to want to. He will be asking unhelpful questions in the parliament and will attract huge amounts of publicity. If she is moving too slowly then he will appeal to the more radical elements in the SNP to join him in forcing the issue and pushing for an immediate unofficial referendum or other expression of a “claim of right”. He and his small band of MSPs may in effect hold the balance of power in the new parliament so far as independence is concerned. Depending on how the seats fall, Ms Sturgeon will have to do deals with the Greens and Alba to get things done, with the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats trying to be unified for the union as their tribalism will permit.

In Mr Salmond’s world the SNP and Alba Party together will sweep all before them in any event; that is not certain to transpire. It is certainly difficult to envisage Ms Sturgeon offering Mr Salmond any jobs in her government, not even being in the same room for any political talks. If so, then minutes might well be taken next time round.

“Alba” is a self-consciously Gaelic political label, and an implicit rejection of anglicisation, like Sinn Fein, Fine Gael and Fianna Fail in Ireland (or Eire), and Plaid Cymru in Wales. It has a romantic feel, it dates back to an independent Scottish kingdom more than a thousand years ago, and is an obvious reminder of Scotland’s long status as a sovereign nation long before the Act of Union of 1707, regarded by some as illegitimate. The pronunciation of its name may not be the only point of issue as the Alba Party and its controversial chief makes their presence felt on the Scottish political scene.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments