‘Vital’ for Britain’s reputation that aid budget cut is temporary, former top diplomat warns

Exclusive: Sir Simon McDonald says timing of spending reduction ‘could not have been worse’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The former top diplomat at the Foreign Office has warned it is “vital” for Britain’s reputation that the government ensure a contentious multibillion-pound cut to the overseas aid budget remains a temporary measure.

In his first public remarks on the issue since leaving his role as permanent secretary, Sir Simon McDonald said the timing of the spending reduction “could not have been worse”, coming just months after the Department for International Development (DfID) was merged into the Foreign Office (FCO).

Lord McDonald, who will deliver his maiden speech in the House of Lords this week after being awarded a life peerage, claimed the UK remained in the “premier league” for aid spending, but told The Independent: “There’s no way to present this as a great move”.

Last year, the government reneged on its election manifesto pledge to maintain 0.7 per cent of gross national income on overseas aid spending, as Rishi Sunak announced at November’s spending review that it would be reduced to 0.5 per cent — a cut of around £4bn.

Due to the severe impact of the coronavirus pandemic on Britain’s economy, the UK’s Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) spending had already been drastically reduced last year.

Within weeks, the government will have to decide which aid programmes to cut or scale back in the coming financial year, and on Monday the United Nations will hold a crucial pledging event when member states will be expected to announce pledges to address the humanitarian crisis in Yemen.

The UK government provided around £200m to the war-ravaged region in 2019, while a further £214m was pledged in aid throughout last year to address “famine conditions”, with citizens facing starvation, death and destitution. It is understood the foreign office minister James Cleverly will attend the meeting.

Asked whether the overall cut to the overseas aid budget would undermine the “global Britain” strategy pursued by Boris Johnson’s government, Lord McDonald replied: “£10bn is still a huge amount of money, and if you look around the OECD, the number of countries that are at or close to 0.7 is very small.

“I don’t think that this undermines our reputation, I think we are still in the premier league of ODA donors, but it’s still a cut the community is very sensitive to and minds, even if it doesn’t demote us to a lower division among aid givers.”

However, he went on: “It’s clearly not ideal: the timing – to say the least – is unfortunate. It is vital to our reputation to stress that it is temporary and that we plan to restore the 0.7 per cent. I can buy the government’s narrative on this.”

“They [the government] have said it was temporary and that their ambition was to restore it.”

Lord McDonald added: “There’s no way to present this as a great move. The fact we were at 0.7 per cent was widely praised in the development community. That we are no longer a 0.7 per cent spender is going to be noticed and regretted. But given the pressures the economy is under, the government is under, it’s something that can be explained while simultaneously being regretted.”

Announcing the cut last year – opposed by four living UK prime ministers – the chancellor Rishi Sunak said it would be temporary, but did not set a date for the budget being restored, saying only: “Our intention is to return to 0.7 per cent when the fiscal situation allows”. Foreign secretary Dominic Raab also told MPs he could not guarantee when the multibillion-pound cut could be reversed in the “foreseeable, immediate future”.

Lord McDonald said he was not surprised by the announcement, but stressed the timing, given the earlier decision to merge the two departments, “was to say the least unfortunate”.

He added: “This is a merger I believe in. I think that the UK, if it is to carry weight on the international stage, needs a single foreign policy, so having one ministry lead is logical, but looking at component parts, the FCO half was much happier about that idea than the DfID part.

“We are in the early stages of a merger which is particularly controversial amongst the development aid community, and within weeks the budget is at least temporarily cut, so the timing could not have been worse, even though I understood the motivation.

“My second thought was there were other ways to skin this cat, and one of the things I hope will change over time with our spending of ODA is that we will spend it on a wider variety of issues. That is what I would have advocated had I still been in the Foreign Office.”

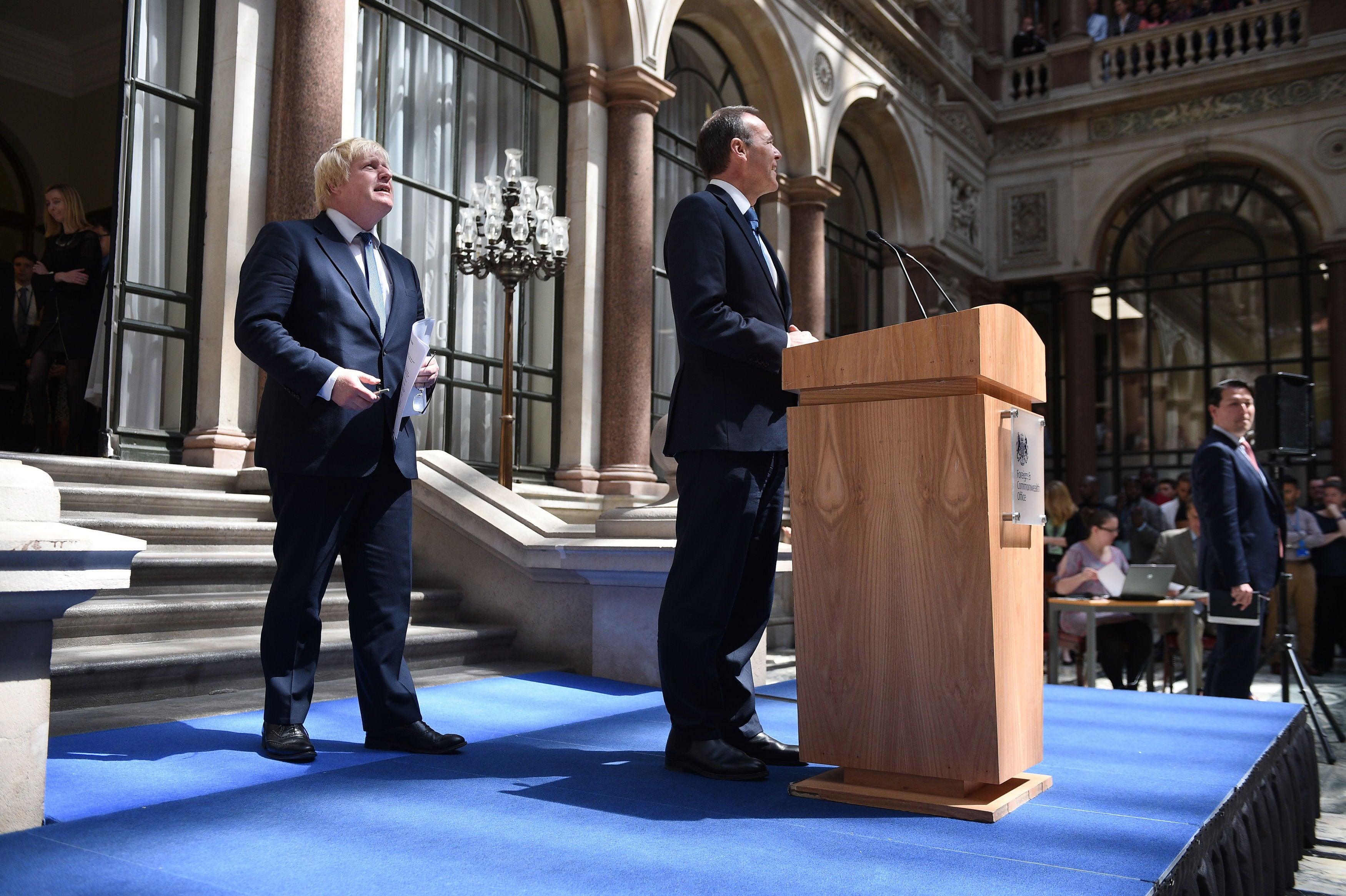

Lord McDonald, who was reportedly identified on a Whitehall “hit list” of three permanent secretaries No 10 wanted to replace before he left his post last summer, served as the most senior civil servant at the Foreign Office between 2015 and 2020, working closely alongside Philip Hammond, Jeremy Hunt, Mr Johnson and Mr Raab.

Pressed on his experience of working with Mr Johnson while he was foreign secretary, Lord McDonald, who first joined the diplomatic service almost four decades ago, replied: “I enjoyed working with Boris Johnson.

“I was running the Foreign Office, and he was a clear, personable foreign secretary to work for. He knew that I was not a Brexiteer, but he also knew I was a civil servant and I knew my job was to deliver the government’s policy as best as I and my ministry could. On that basis we had a good working relationship.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments