Not so black and white: Why the reasons for New Labour's rise and fall are more complex than we think

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

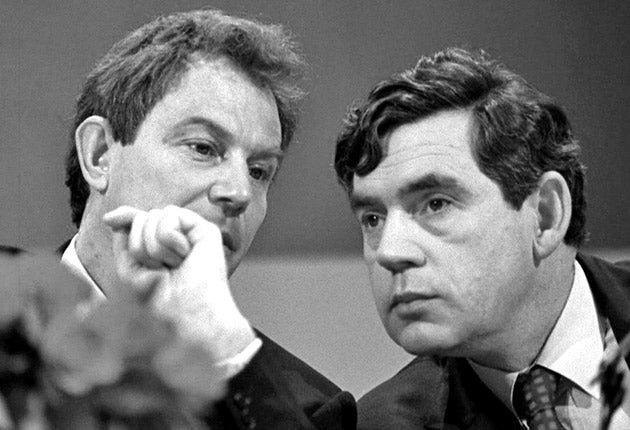

Your support makes all the difference.The drums roll. With a publicity machine that becomes a story in itself, Tony Blair has his say about the New Labour era. Peter Mandelson has his, too. They speak loudly and selectively as they leap back on to the stage. They are not alone.

There is a mountain of diaries, books and autobiographies that seek to make sense of New Labour. They began to appear before Labour was elected in 1997 and continued pouring out afterwards. Yet the mountain obscures and distorts the view. We need to make our way around it as a matter of urgency – for the past, or perceptions of the past, shape the present and the future.

Supposedly mighty leaders have no idea what will happen next in terms of their own fates or in relation to the dizzying twists and turns of fragile economies. All of them rule with their fingers crossed. Lacking a clear route map, most of them look to the past as a guide. Margaret Thatcher resolved not to make the mistakes of Ted Heath in the early 1970s. Tony Blair grew up politically in the 1980s, when Labour lost elections appearing to be high taxers, reckless spenders and soft on defence. He would be for low taxes, support wars and be unequivocally pro-American. His outlook was shaped almost entirely by his party's past. On the doorstep of No 10 in May 1997, he offered no glorious vision of the future. He did not have one to offer. Instead he stressed he would govern as New Labour and not old.

David Cameron followed suit by copying the techniques of Blair. His party had seemed harsh and uncaring. He would build a big tent. The past was his guide. It still is. Senior ministers in the Coalition read Blair's memoirs avidly and gullibly to learn lessons. His version of the past is their new bible.

They should worship with care. The immediate past is the most treacherous guide of them all. We make assumptions that are contradictory, or at the very least contradict what we thought at the time. Assertions about recent events are made that sound convincing until they are analysed for a moment or two, and then they cease to make much sense at all.

The New Labour era has ended in a state of seething retrospective muddle... Blair was a great crusading domestic reformer who was blocked by Brown... Blair was weak and self-deceiving, so weak that he failed to remove Brown... Mandelson's great crime when he returned to government was not to use his power to dump Brown... Blair was not especially good as Prime Minister, but might have been better if he had removed Brown, who followed a reckless economic policy and was opposed to "change"...

One of the fascinations about history is the way our perceptions of what happened constantly change. The assumptions that are broadly shared now are very different to some of those previously held. There were times when Brown was regarded as a mighty Chancellor steering a prudent economic course. In the build-up to the 2005 election, Brown was so popular that Blair had to bring him back to the centre of the campaign and be filmed buying him an ice cream to convey misleadingly a friendship of almost childish innocence. There were times when Brown's personal ratings were remarkably high for a Labour Chancellor who had taxed extensively and had been in charge of economic policy for what seemed like an eternity. Chancellors, especially Labour ones, tend not to last very long. Could Brown have been mad, bad and incompetent when he was a long-serving Chancellor and a leader in waiting for more than a decade who became a leader?

Some of those condemning Blair now for failing to sack Brown were posing an entirely different question in 2004: why doesn't Brown remove Blair in a coup? In fact, Brown's reticence was good judgement. His nightmare as Prime Minister would have been even worse if he had overtly committed an act of regicide. Brown had no space to remove Blair. Blair never had room to dump Brown, not least because no alternative replacement would have had a clue what to do about the economy.

Blair did not have much of a clue, either. A great misreading of the New Labour era relates to economic policy. In his memoir, Blair claims to have been in charge of macroeconomic policy until the end, when it started to go wrong. This is laughably self-serving and misleading. When Blair became leader in 1994, Brown was already beginning a titanic reworking of Labour's economic policy and was more or less allowed to get on with it, or asserted his right to do so, for the next 13 years.

Here is one of the great missing gaps in current New Labour mythology that distorts the present and possibly the future. Brown's dominance of economic policy is overlooked or misunderstood. The downside was the partly understandable neurotic possessiveness after he became shadow Chancellor in 1992. From then on, no Labour figure was allowed to think about economic policy. This has produced a weird situation where internal Labour debates are largely free of economic policy even now Brown has stepped down. The exception in the leadership contest is Ed Balls, the only Labour figure apart from Brown allowed to think about economic policy from 1992. He did more than think. He devised much of it. What is a Miliband economic vision and the detailed policies to accompany it, one that wins broad support and will not be torn apart by the media? Without one, Labour is doomed.

The upside for Labour after 1992 was that within a few years, Brown was able to answer that question. He rewrote his party's approach to the economy from 1992 in a way that won wide support and yet enabled him over time massively to increase investment in public services while to some extent redistributing income, too. When he became shadow Chancellor in 1992, Labour had lost a fourth successive election because it was not trusted to run the economy. By 2001, it had won two landslides and was beginning the long haul to lift Britain out of public squalor. Arguably Brown took too long to invest and unquestionably he was too reliant on the financial services, but those tiny spaces in which senior public figures function are part of the explanation. Labour was not trusted with the economy. The "threat" of tax rises had lost Labour elections. Yet there needed to be a massive increase in public spending. In 1997, Brown could have spent vast amounts of time and political capital reining in the City and being slaughtered for doing so, or redirecting the profits towards the crumbling public services. He chose the latter.

While Blair was proclaiming his boldness, Brown peaked as a politician with his Budget in the spring of 2002 when he implemented a tax rise to pay for improvements in the NHS. The preparation for the move was deft and afterwards, polls suggested even a majority of Conservative voters supported the Budget. Brown had taken Labour from a position where his party was not trusted to spend 50 pence on an ice cream, to a place where it could openly put up taxes in order to improve a public service.

The fact that some of the money raised could have been better spent is a very big political issue, one that Labour ignores at its peril. But the causes of the waste are many. Some of the so-called reforms were costly, from the public-private partnership for the London Underground (Brown's) to the deals secured by companies seeking contracts in the health service (Blair's).

Somehow Blair managed to pose the debate about the future of public services as one between pro-reform and anti-reform, as if there was a single route available, building on the Thatcherite changes introduced in the 1980s. Blair argued that he was being bold and modernising when he was continuing with past experiments and had the support of most of the mighty newspapers in doing so.

One of the many reasons Brown was trapped fatally by the time he became Prime Minister in 2007 was that he knew some of Blair's reforms were chaotic, over-hyped, or unachievable, and yet he ached for the support from the same newspapers that supported Blair's version of reform. He did not dare break with Blairite Thatcherism out of fear of the onslaught from parts of the media and ultra-Blairites in his party who regularly poured poison in the ears of influential columnists, mainly alleging that Brown's entourage were malevolent briefers. In the end, Brown was as scared of the ultra-Blairites as they were of him.

Yet he was a reformer. Brown dared to take on the Treasury and reform the institution. This made him unpopular and led to accusations that he was Stalinist, but better that than a weak Chancellor at one with his mandarins in accepting the wrong orthodoxy, a danger at the moment. Brown established Bank of England independence, tax credits that rewarded work and for a time provided space for public spending increases. He also had a political strategy that was effective, which was to develop a reassuring public narrative while implementing radical change. Knowing it was impossible to win a policy argument in the British media in advance of implementation, he would seek to win it once the policy had been implemented.

The debate over choice in public services was about practicalities, coherence, political judgement, accountability and fairness. In September 2001, Brown said to me that in the US he had seen a poster from a candidate with the slogan "Choose Freedom". Brown joked that as far as he knew, the other candidates were not against freedom. He suggested the debate about choice was similar. Who could be against choice? But was the public willing to accept the surplus of empty places in schools and hospitals necessary to make choice feasible? Would they be willing to pay for this huge leap when most public services were still creaking? He supported what Ed Balls calls managed choice, on the basis that the central government was raising all the cash and taking risks doing so. He could not let go entirely. There will be similar internal debates in the Coalition about the conundrum: how do governments give away power while being responsible for raising the money spent by the newly empowered? There is no easy answer. Instead of revering Blair uncritically, Cameron, Osborne and Gove should follow more closely the detailed policy debates between Blair and Brown.

Form 1992 to 2002, Brown was the biggest figure in British politics. After that, his crazed ambition drained him and affected his judgement. When he was Prime Minister, he was exhausted and had alienated too many colleagues. Even then, he took a course that averted catastrophe in the financial crisis. Blair suggests in his memoir that he would have taken a less "statist" approach, in which case there would have been a danger of several banks collapsing.

Currently Brown does not have a hope. Some of his oldest allies are scathing as they reflect on his final years in power. But take Brown out of the equation and Blairite New Labour would have been little more than an echo of outdated Thatcherism. Much of the current criticism against Brown is valid, but the full story is far more complicated than fashionable orthodoxy suggests. There was more than one journey and the next Labour leader, along with senior ministers in the Coalition, should take a very careful look at what form the other one took.

Steve Richards' book 'Whatever It Takes: The Real Story of Gordon Brown and New Labour' is published by Fourth Estate today, price £14.99. To order your copy at the special price of £13.49 (free P&P), call Independent Books Direct on 08430 600 030, or visit independentbooksdirect.co.uk. His Radio 4 series 'The Brown Years' will begin next Tuesday at 9am. His one-man show 'Rock'n'Roll Politics' is at Kings Place, London N1, on 4 October.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments