Northern Ireland assembly elections: Can Thursday’s vote save power-sharing?

Polls open on Thursday after the collapse of power-sharing last month when Sinn Fein refused to return to Stormont executive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Northern Ireland is in full election mode, on the eve of polling day. As is custom in the region, lamp posts lie littered with large plastic election placards, blaring candidates’ names and either the Irish flag or Union Jack, depending on residents’ religions.

In hotly contested seats, parties plaster their propaganda on every surface available, from railings to low hanging trees, blossoming like strange fruits.

If the scene sounds strangely familiar, that’s because it is. Northern Ireland is facing its second election in less than twelve months.

This election, however, is no mere re-run of elections past, but rather a last ditch attempt to save power-sharing between Protestant and Catholic parties.

The collapse of the last Government was a historic and surprising blow to the peace process.

It followed months of splintering relationships between power-sharing partners at Stormont which finally saw Sinn Fein pull the plug on parliament and walk out on their coalition counterparts, the Democratic Unionist Party.

The dramatic collapse of power-sharing came after a scandal involving the Democratic Unionist Party, amid allegations they were responsible for a botched heating initiative which resulted in people being paid to burn money pointlessly.

The scheme is thought to have cost the Northern Irish tax payer close to half a billion pounds, and occurred on the DUP’s watch while their leader, Arlene Foster, was an executive minister.

The DUP and Ms Foster deny any wrongdoing and refused to step aside amid mounting public anger, prompting Sinn Fein to announce they no longer have faith in the partnership and were pulling out of power-sharing.

As a result, Northern Ireland Secretary, James Brokenshire, has been forced to call new elections in a bid to return a fresh government which will be willing to return to power-sharing.

If the election wields new results to that of last May, politicians may agree to return to power-sharing and attempt to resurrect the institutions.

However, if the same politicians are returned, Sinn Fein has already said it will refuse to power-share with DUP leader Ms Foster, raising the possibility that devolution will not be restored and Northern Ireland will instead have to be run directly from London.

I meet the Green Party’s Deputy Leader Clare Bailey at her constituency office in South Belfast. She is one of Northern Ireland’s newest members of parliament, or MLAs, who was elected last May in the most recent election.

As we meet, her office is still a hive of activity with just short of 24 hours to go until the polls open.

Students from the nearby Queen’s University Belfast are dropping by throughout the day to send off last minute election material.

“It is the oddest election I’ve ever fought”, she tells me. “Anyone who tells you they know which way this election will go is bluffing.”

Northern Ireland has famously unique politics, with voters more likely to cast their ballots based on their stance on the constitutional status of the region, rather than social issues which dominate elections across the water in Great Britain.

Unionists, who are most often Protestants, support Northern Ireland remaining in the UK, and tend to vote for the DUP, or their more moderate counterparts, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP).

Nationalists, who are most often Catholics, support Northern Ireland reuniting with the Republic of Ireland, and tend to vote for Sinn Fein, or the more moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP).

Within the middle ground, the anti-sectarian Alliance Party takes votes from moderates across the region, who prioritise social issues and cross-community peace above the national question.

The Green Party is increasingly challenging them for votes on a similar platform, as is the anti-austerity social party People Before Profit.

Over coffee in her constituency office, Ms Bailey explains that the scandal the DUP was involved in appears to have rocked traditional voting allegiances, with their usual core vote feeling deeply disillusioned.

“Responses we’ve been getting at the doors when out canvassing have been divided into two camps," she said.

"We have young people who are excited [to see another election] as they think its a change and a chance to see new politicians elected.

"But for older generations, many are disillusioned. In some areas which traditionally vote DUP, people tell me that for the first time in their lives they’ll not be voting. It’s heartbreaking.

"They’ve been through so much in Northern Irish politics but are just so disillusioned now that they feel they have no one to represent them anymore.”

Indeed, the neighbouring constituency of Lagan Valley, which borders Belfast and the nearby small city of Lisburn, is a striking example.

Seymour Hill is a large council estate in the area, which is staunchly loyalist and bears union jack flags and bunting proudly hung on homes and shops, along with curb stones daubed in correspondingly patriotic red, white and blue.

Amid this blur of British pride, a freshly painted sign can now also be seen. It states, ‘taxi for Arlene’, a gibe at the party’s leader in an estate once taken for granted as the safest of seats for the Democratic Unionists.

Across town in West Belfast, the focus of election discourse is vastly different.

The Republican area is the home of Sinn Fein, who safely dominate the ballot box, but have seen recent challenges from socialist party People Before Profit.

Here, election material is printed in the Irish language, which Sinn Fein promotes. ‘Comhionnanas Anois!’ or ‘Equality Now!’ blares one lamp post.

In Andersonstown, one of the most Republic areas of this part of the city, a gigantic poster with images of Sinn Fein old guard Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness flank one of the party’s new leader Michelle O’Neill, before a suitably Republican garish green backdrop.

Ms O’Neill took over the mantle of the party just six weeks ago, following Mr McGuinness’ resignation on health grounds.

For her this election has been a baptism of fire into the leadership role, which she has so far been handled well.

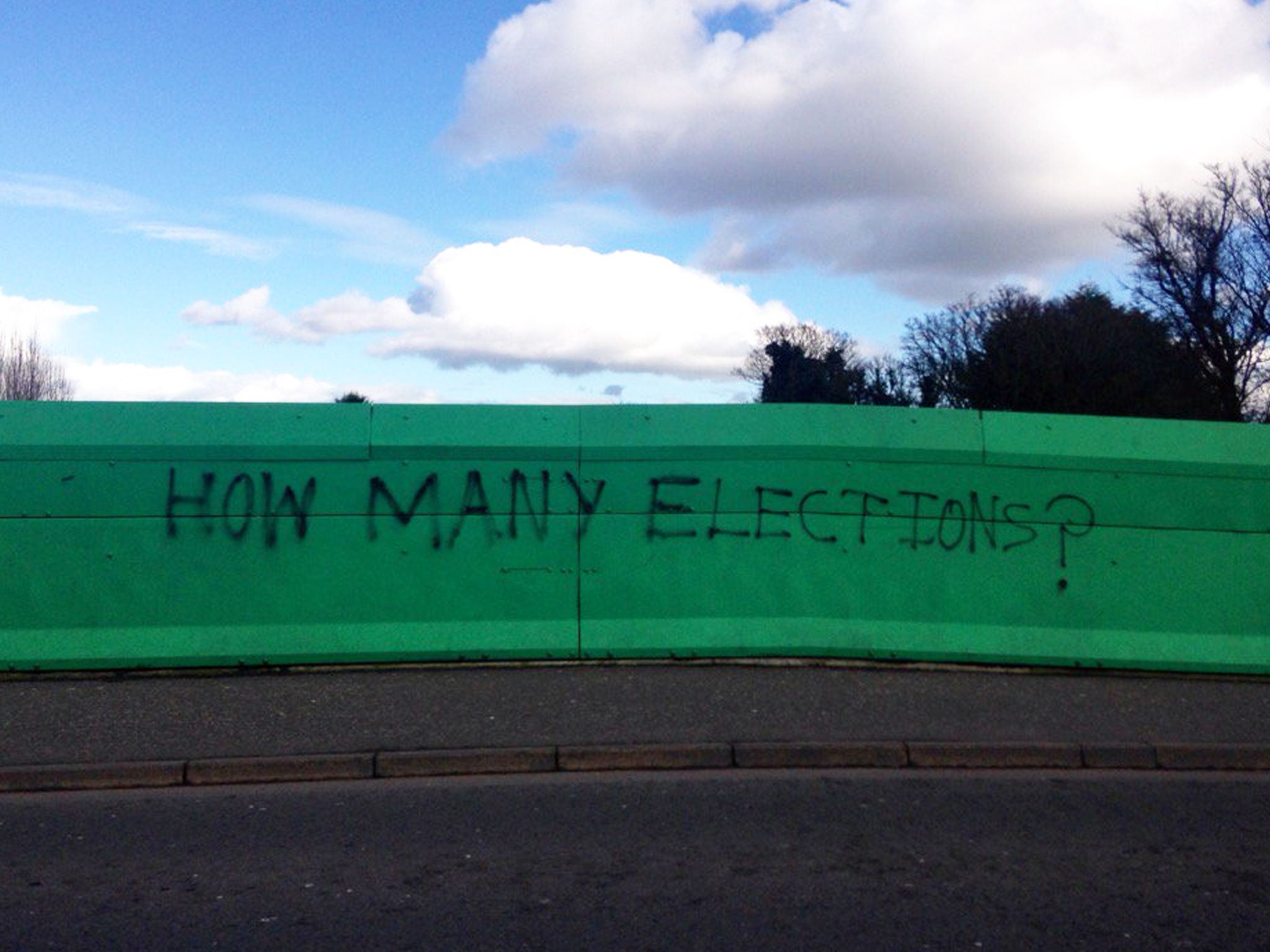

Away from the official party election material, however, one significantly less slick message might sum up best the feelings of the general public.

On the Finaghy Bridge, which links Andersonstown with the more affluent Finaghy village, one local has scrawled a protest message in black spray paint.

“How many elections?”, it asks, expressing much of the disbelief and disillusion with the apparent regression in power-sharing that has made this crucial election come about.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments