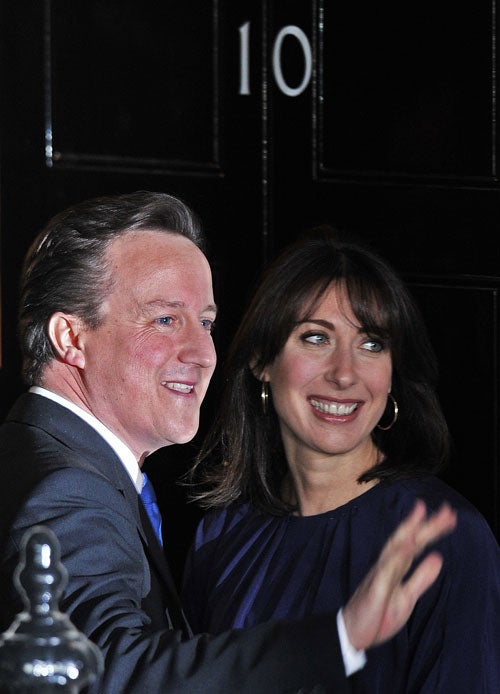

No 10 under Cameron: The three acts of the PM's leadership

He wanted to restore cabinet government and bring order to Labour 'anarchy'. But not everything has gone to plan

In the first few hours, it was a race for the best rooms and the best desks, said a young Cameron aide in the immediate aftermath of Gordon Brown's hurried departure from Downing Street last May. Unbeknown to the younger members of David Cameron's team, much thinking had in fact already taken place. George Osborne, who was to become Chancellor, Ed Llewellyn, Cameron's chief of staff, Kate Fall, a friend of Cameron's since Oxford and deputy to Llewellyn, and Steve Hilton, who had been responsible for much of the strategic thinking in opposition, had been meeting in strict secrecy. Llewellyn met Jeremy Heywood, the senior civil servant in No 10, and reached an understanding about how the place was to be structured in the event of a Conservative victory. They sketched out who would have each office and decided that they would have a relatively small policy unit and political office.

Heady first days: May 2010

For Cameron's senior team, the fact of the coalition weighed heavily with them. "We decided we were going to bond with the Liberal Democrats from the very start," said one. They decided, "within hours", to bring Lib Dem advisers into the heart of No 10. "The relationship with Nick Clegg [the Lib Dem leader] was going to be critical. We had to create a single government."

Optimism: May to November 2010

No 10 has been through three clear phases under Cameron. The first lasted until October/November, and was a honeymoon phase. Cameron was clear from the outset that he was going to bring order and calm to what he saw as the havoc and chaos of Brown's regime. Civil servants noted with approval that "paper was back in vogue".

For the first time since John Major's period in office, the Prime Minister has a proper red box sent up to his flat each night full of a "thick wodge of papers". Cameron gets up at 5.30 every morning and spends two hours working systematically through them. He then chairs two meetings each day from his office at the end of the Cabinet Room (Osborne takes the chair when Cameron is away). The 8.30am meeting provides a structure for the day, then a meeting at 4pm reviews progress. Regular attendees are Osborne, Llewellyn, Hilton, Fall and Heywood, as well as rotating Cabinet ministers, with William Hague a regular presence.

Cameron was equally clear that his premiership would see a return to formal Cabinet government. Cabinet meets for an hour and a half to two hours each Tuesday. Other regular meetings include the National Security Council, which he established at the outset of his government, and a weekly bilateral meeting between Cameron and Clegg, the Deputy Prime Minister; the "quad" – consisting of Cameron, Osborne, Clegg and Danny Alexander, the Chief Secretary to the Treasury – has become a key feature of government. Officials expressed delight at the "return to formality and commitment to process" after the more anarchic style of Labour.

One can best understand the influences on Cameron by breaking his world into a number of segments corresponding to his roles as premier. Within each, one can discern an inner, middle and outer ring of influence. With Cameron, influence can be measured by those he trusts the most: "It's not how often you see the PM," said an aide, "but whether your intuitions chime with his."

The first area, policy advice, saw one figure alone in the inner ring of influence: Steve Hilton. His exact role has always been difficult to define as he operates in the freewheeling, informal style of his days in advertising. His influence derived much from his close relationship with Cameron and his lead role on key policies, above all the idea of the Big Society.

In the middle ring stood James O'Shaughnessy, head of policy in Cameron's opposition team, who initially became head of the embryonic policy unit. In the outer ring stood Rohan Silva, who joined as No 2 in the policy unit, spending most of his time on day-to-day issues while O'Shaughnessy focused more on strategic questions.

Polly McKenzie, the Lib Dem's senior figure in No 10, became important early on. She was given one of the two prized offices off the Cabinet Room's ante-room, which she shared with Hilton. Her role was more concerned with strategy than policy, and she rapidly became "a valued and trusted member of Cameron's team".

On the political side of No 10, in the inner ring stands Ed Llewellyn, who continued with the title chief of staff, a position created by Tony Blair for Jonathan Powell in 1997. A protégé of Chris Patten's, Llewellyn had acted as chief of staff to Cameron throughout his time as leader of the opposition. Foreign policy was a further expertise of his, having worked in Hong Kong, Bosnia and Brussels. Cameron came to rely heavily on his advice in this area.

Kate Fall decides who gets to see the Prime Minister and to what he pays attention, which gives her unique power. She helps sort out his diary, deals with politicians, and is close to him personally. Modern prime ministers seem to need to have a particularly close female aide, and Fall is as influential as any. In the outer circle is Stephen Gilbert, the political secretary, who acts as the bridge between Cameron and the Conservative Party, both in parliament and in the country, and is influential on party political campaigning.

Communications and the press office is a third side of No 10. One figure utterly dominated the first phase: Andy Coulson, who had joined Cameron's team in 2007 as communications director. A former editor of the News of the World, he was one of the most forceful influences on Cameron in the first few months. In the middle circle stands Gabby Bertin, at 32, one of the youngest members of the team. She became Cameron's chief press officer in 2005. He frequently seeks her advice. In the outer ring is Steve Field, a civil servant who was the prime minister's official spokesman.

Civil servants have historically been important in No 10. The political figures who joined the new government at the same time as Cameron looked with a mixture of awe and envy at how well organised they were for the task ahead. The most powerful of them is Jeremy Heywood. He had been the prime minister's principal private secretary under Blair and was recalled by Brown in January 2008 as permanent secretary at No 10. He impressed Cameron: aides described being awed by his magisterial authority and knowledge, apparent to them from the first evening.

Cameron leant heavily for foreign policy advice not only on Llewellyn, but also on Peter Ricketts. Continuity was provided by Tom Fletcher, a Foreign Office official who had become a dominant figure under Brown. James Bowler, a "formidable worker", continued as the principal private secretary from Labour and occupied the office beyond Cameron's, off the end of the Cabinet Room.

Cameron inherited the urbane Gus O'Donnell as Cabinet Secretary. They have a weekly bilateral meeting and discuss the agenda for Cabinet carefully together. Officials believe that he is closer to the Prime Minister than any cabinet secretary in the past 20 years. Cameron is now relying heavily on O'Donnell to manage the slimming down of the Civil Service, and to assure the people who work within of his respect for the service.

Cabinet ministers constituted the final influence, with one predominant figure in the inner circle from the outset: George Osborne. Still close to Cameron, but not in the same league as Osborne, came Michael Gove, William Hague and Oliver Letwin.

The first phase of the new rule was judged by No 10 to have been exceptionally smooth, above all in establishing a sense of calm and purpose from the centre, and a reputation for running a coalition government with confidence. The key challenges in the first six months were the Budget, the spending round, welfare and education reform, foreign trips, including one to Washington, the defence review, and cementing the relationship with Angela Merkel in Germany and Nicolas Sarkozy in France.

Transition: November 2010 to February 2011

By September or October 2010, it had became clear that the initial model of No 10 was no longer working optimally. The protracted and draining tuition fees saga and the furore over the proposed sale of forests combined to puncture the optimism of the first few months. The election of Ed Miliband as Labour leader in September, and the subsequent promotion of Ed Balls to shadow chancellor following the resignation of Alan Johnson in January 2011, further changed the mood in No 10.

Questions were asked about the spending of political capital on relatively unimportant areas such as sports partnerships, and about strategic grip. By Christmas, the lack of co-ordination between the policy and press side was becoming serious. From September, Cameron began talking to Heywood, Llewellyn and Fall about bringing in extra staff, and they spent the autumn identifying the right people who would bring the momentum it needed.

Beefed up: March 2011 onwards

Coulson's departure in January over the phone-tapping saga provided a catalyst for the third phase in No 10's evolution to begin. Craig Oliver, the BBC's global news controller, was appointed head of communications at the end of February. The impact was felt immediately. Coulson had never been a fan of the Big Society, and relations with Hilton had become difficult. His departure allowed Hilton to promote his favourite policy far more intensively. Relations with News International, from whose stable Coulson came, juddered, and the press team began to engage far more heavily with commentators, who had never been Coulson's natural milieu.

Another key appointment was that of Andrew Cooper, the Populus pollster and former Conservative strategist, who joined No 10 in a newly created role of strategy director, aiming to better connect policy and the electorate (the role that pollster Philip Gould had played for Blair) and to help co-ordinate strategy more effectively.

Major changes to the policy side have come in this phase. The strategy unit, which had been inherited from Labour, was disbanded: it was considered too ponderous and unresponsive. Paradoxically, it also became clear that more policy wonks were needed, both political appointees as well as officials with in-depth knowledge of how Whitehall operates. A new research and analysis team was established, and an expanded policy unit was built up. These report directly to Cameron. It is given political direction by Hilton and by Silva. Letwin remains a crucial influence on policy.

The unrivalled inner ring of advisers in this third phase are Osborne, whose influence has remained unchanged, Heywood, Llewellyn and Hilton, who together, in effect, run No 10. Hilton absorbs himself in the policy and implementation as well as strategy, leaving some issues that do not fascinate him, like higher education, to Heywood.

Hilton's job combines that of Lord Adonis, Blair's best head of policy, with that of Michael Barber, his delivery wizard. Heywood, meanwhile, ensures that No 10's official machine, and Llewellyn's No 10 political teams, run smoothly. On Libya, he is relying on Ricketts' advice daily, not least at the daily meeting of the National Security Council's Libya committee.

Left out of this analysis is not only Andrew Feldman, the co-party chairman and close confidant of Cameron, but also the only figure who vies with Osborne, Llewellyn, Hilton and Heywood for influence with the PM: Samantha Cameron.

Whether the third phase will provide sufficient firepower and capacity for the Prime Minister is yet to be seen. The history of modern premiership is typically one of high initial ambitions and excitement followed almost always by disappointment. More firepower, not less, could be the key.

Additional research by Laura Gibbons.

Anthony Seldon's latest book in his series on No 10 was 'Brown at 10' (Biteback, 2010). He is also co-author with Dennis Kavanagh of 'The Powers Behind the Prime Minister' (1999, HarperCollins). A longer version of this article appears in the April issue of 'Parliamentary Brief' www.parliamentarybrief.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks