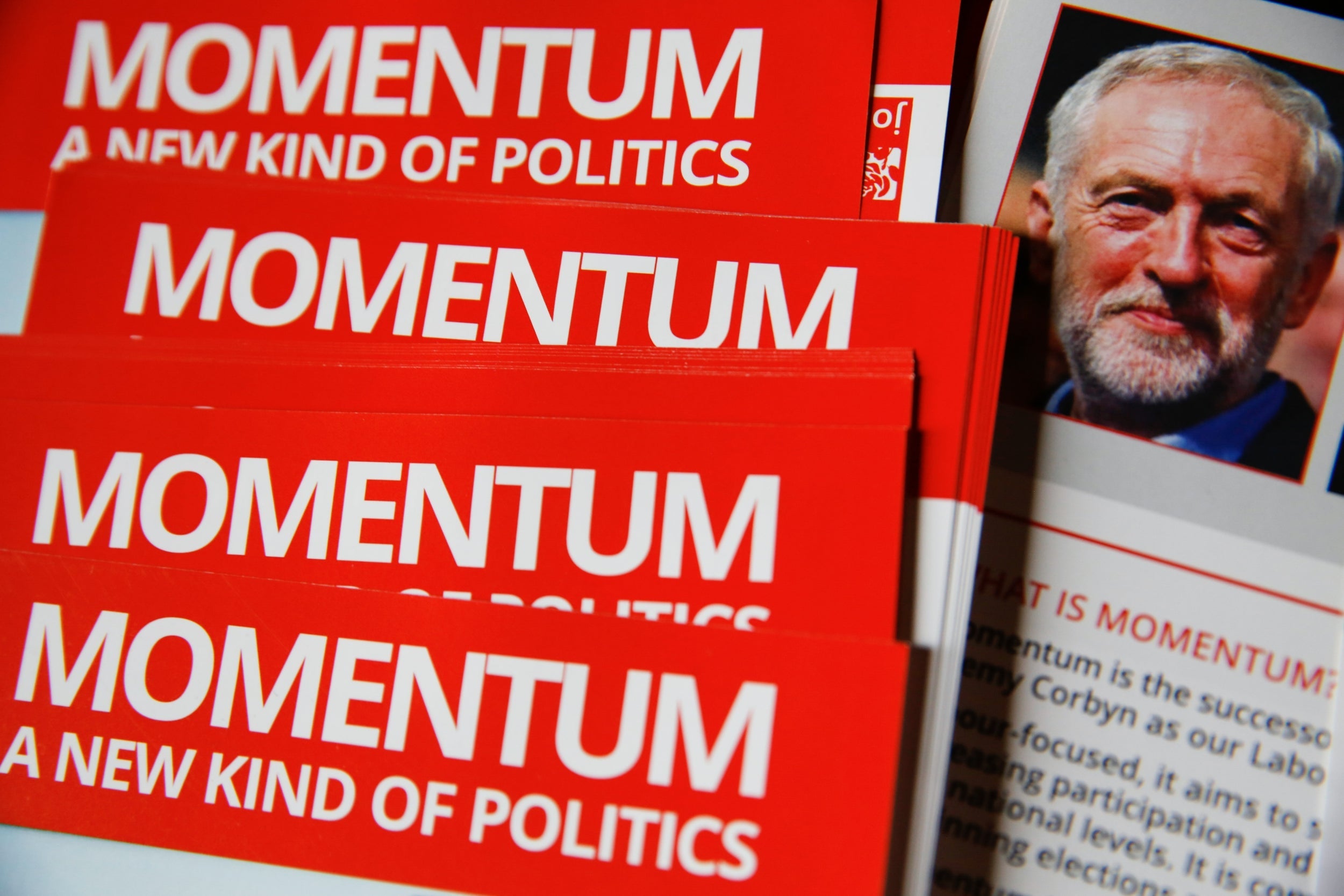

Is there life after Jeremy Corbyn for Momentum?

From left-wing ‘rabble’ to the forefront of Labour’s digital campaigning, the group has transformed in just four years. But, writes Ashley Cowburn, now it’s at a crossroads

A parasitic organisation, a bit of rabble, proof of a Trotskyist infiltration, a theatrical cult. These were just a handful of the phrases used to describe Momentum, the group of activists on the left of the Labour Party, in its early days. They would have likely been far worse had one of the other names put forward been chosen: swarm.

“Look, when you ask people to come up with ideas for names, what they do is they can think of two or three good ones, or reasonable ones, and then try to make up the numbers,” says founder Jon Lansman. “I think Swarm wasn’t even on the bottom rung. That got the biggest laugh.”

The grassroots organisation was set up by Lansman, alongside Adam Klug, Emma Rees and James Schneider, in the wake of Jeremy Corbyn’s 2015 leadership success. They had all worked on the Labour leader’s surprise victory, and sought to harness the energy behind that campaign to build a social movement supporting Corbyn’s left-wing policy agenda – drawing inspiration from anti-austerity movements in Europe, including Syriza in Greece and Podemos in Spain.

Four years later, sitting in Momentum’s Finsbury Park office, serving as an election headquarters close to the Labour leader’s constituency office, Lansman, who is wearing an orange tie-dye Grateful Dead T-shirt, reflects on the name they eventually chose. “It’s very difficult when you’re trying to think of a name; people associate the word with what they think the words means, rather than what they think it will become once you create a big organisation which has a big effect. And then the word acquires a completely new meaning which is how people see what Momentum became. Obviously it reflected the momentum that increased during the course of the leadership campaign.”

What Momentum became is a group boasting 40,000 members paying a minimum of £3 per month that has put itself at the forefront of Labour’s push to win next week’s general election, raising £500,000 in donations to be used on canvassing by its army of activists and innovative digital campaigning. But that is a far cry from where it all began.

* * *

As Corbyn’s popularity grew in the 2015 leadership contest, those intimately involved in the campaign decided a separate organisation was required to ensure the energy from the tens of thousands of members who joined Labour did not dissipate. Lansman, who had cut his teeth 34 years earlier in Tony Benn’s deputy leadership campaign, crucially had also kept the email list of Corbyn supporters.

Welcoming its eventual launch, Corbyn said at the time: “We need to put our values, the people’s values, back into politics. To do this, we need to keep up the momentum we have built over the last four months.”

But today, Lansman admits Momentum launched “before we were ready”, adding: “We didn’t have a constitution, we’d had all these groups spring up around the country organically, we didn’t organise them. We didn’t have the rules, we tried to impose – because we launched without a constitution – we tried to impose some rules on them.”

“It was a turbulent time,” Lansman adds. “We had people who weren’t members of the party, people who perhaps had paid £3 to vote, but had decided not to join the party. It was a difficult time to establish an organisation, but we did and we have established a new, left organisation, with a culture that is very different from any left organisation.”

Lansman says he did anticipate a pushback against the organisation. “That came straight away, before he was elected,” he says. “As the disbelief ground down a bit, it was replaced with more animosity. It was not the whole PLP [parliamentary Labour Party] at all, and the most vocal, most aggressive were a small minority in the PLP, most of whom, or many of whom, are among those people who have since left the party”.

Momentum faced considerable conflict with the party’s MPs at Westminster over the highly contentious issue of deselections. Those opposed to the party’s new leadership viewed the organisation as a threatening force, seeking to purge critics of Corbyn from the Labour Party, while activists pointed to increasing internal democracy and enfranchising party members.

The threshold for MPs to be “triggered” was reduced at last year’s Labour conference, and Lansman says there is still “further to go” in handing party members more powers – pointing to the group’s failure, so far, to introduce “open selections”.

There’s a tendency with journalists to demonise Momentum. I’ve met Momentum members of all shapes and sizes

“It would have been much better to have open selections where people make positive choices for the candidate they thought would best represent them, rather than having to make negative choices about not wanting a particular person, which I think is more divisive,” he adds.

Critics included former Labour leader Neil Kinnock, who famously denounced the Trotskyist group Militant at the 1985 party conference. Ahead of the first The World Transformed in 2016 – a festival at Labour conference by Momentum activists – he said the “sectarian ultra-left” speaking at the organisation’s events risked endangering the party as a political force.

His concern, he added, was that decent and enthusiastic young people were being “manipulated” by “people from the hard left organising in a less-than-transparent way to secure their aged-old objective, the control of the Labour Party”.

Just last year, the Labour MP Stella Creasy, who had been threatened with deselection in her Walthamstow constituency, was scathing in her assessment of the organisation. “What has Momentum actually achieved? To what single cause can they lay claim? They find time to try to deselect me, but not to take a stand against being in the same lobby as the likes of [Tory MP] Jacob Rees-Mogg,” she told a rally hosted by Progress at the Labour Party conference. “Absolute boys? Absolute melts!”

But, speaking in the dining room of her home in Hackney, east London, Diane Abbott dismisses the criticism of the organisation. “If Neil Kinnock knows more than a dozen Momentum members, I’d be surprised,” the shadow home secretary says. “What he is doing is confusing them with Militant, but they are a different thing.

“The point about Momentum is that it was people who were either in the party or, crucially, joined the party to support Jeremy Corbyn – that’s who they are. There’s a tendency with journalists to demonise Momentum. I’ve met Momentum members of all shapes and sizes, some of them have never been in the party, some of them are very young, some of them are a bit closer to me in age.”

But Lansman acknowledges there have been periods of division, including the “difference of view on antisemitism” allegations. Shortly after Momentum’s inaugural gathering at the Labour Party conference in 2016, Jackie Walker, who was then the organisation’s vice chair, was stripped of her position after considerable criticism of her remarks about Holocaust Memorial Day. “In terms of Holocaust day, wouldn’t it be wonderful if Holocaust day was open to all people who experienced Holocaust?” she told a fringe event. Walker was expelled from Labour earlier this year and has made a film, called Witch Hunt, about her experiences.

“There were people [who] argued, who didn’t share my view of acknowledging the problem with antisemitism and dealing with it, which I think is Jeremy’s position and my position,” Lansman explains. “I don’t agree with that view. I absolutely do not agree with the view that antisemitism is all a smear and a put-up job. I know that is said by people who have not seen the evidence I’ve seen in the NEC meetings that adjudicate on cases, where there is no significant difference between NEC members about almost every case.”

* * *

After Corbyn defeated an attempt to oust him as leader in 2016, the organisation was no longer just a Praetorian guard for the Labour leader during periods of instability. Sweeping changes to the organisation were rapidly executed in early 2017, and Momentum announced it would affiliate to the Labour Party itself. It meant its grassroots supporters were required to be, or become members of, the national party. Those who were expelled from Labour could no longer operate within the organisation.

It then turned its firepower to mobilising activists in marginal seats across the country, using innovative forms of digital campaigning. A developed version of its 2017 snap election app “My Nearest Marginal”, pioneered by Bernie Sanders’ team during the US democratic primaries, which directed activists to areas where canvassing was required, has been created for the December election.

Momentum’s tactics also won plaudits from unlikely quarters in the aftermath of Theresa May’s failed gamble to win a greater Conservative majority. Giles Kenningham, a former director of communications for the party, commented: “Labour have used Momentum to devastating effect. The Tories do not have an equivalent group pushing out their message”.

It is still the situation today that the Conservatives have no equivalent. Within days of MPs agreeing to fight a general election, Momentum dwarfed the funds it raised at the last poll. Staffing at Momentum has been increased from 15 to 55 full-time members, funded by almost half a million pounds of donations, and over 1,400 volunteers have pledged to take an average of two weeks out of work to campaign for a Labour government.

The digital side is coordinated from the north London office space where activists have a paper countdown of “days until socialism” plastered to the wall. The upgraded app – “My Campaign Map” – has had over 1.4 million views and gives advice to Labour campaigners on where they can make the biggest impact. In the week after MPs voted for an early election, the organisation coordinated “Super Saturday” through the app with thousands of activists hitting the streets.

One activist, 32-year-old Jessica Adams, a cultural studies student and Momentum member, claims the app had been “really, really helpful” and she had visited constituencies across the UK, including Chingford and Woodford Green, Kensington, Battersea and Aberconwy. Adams says “My Campaign Map” has been “really effective”, adding that hundreds turned out in Chingford, where the Labour candidate Faiza Shaheen is attempting to unseat the senior Conservative Iain Duncan Smith and wipe out his slim 2017 majority of just over 2,400.

The journalist and Labour activist Owen Jones, who has spent time across the country during the election campaign, says Momentum has played a “pivotal role in mobilising activists” and has helped get activists knocking on doors in both defensive and offensive constituencies. “Momentum played a huge role in just getting people to knock on doors, listen to people and get the critical information needed to pinpoint who the undecided voters are.”

In his Westminster office – the day after the Labour leadership signed up to a winter election – John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor and close ally of Corbyn, describes Momentum as “one of the most successful things that’s happened” to the party. “It’s been a real asset to us all the way through – more than Jeremy, it’s an asset for the Labour Party”.

McDonnell adds: “It’s just a huge activist organisation, in terms of enthusiastic members – most of them young people. What’s interesting, they are very professional about how they operate, they are young people who come up with really creative ideas about how to mobilise, how to engage with people, and their social media presence is so effective. They have these training sessions with people about how to engage in conversation on the doorstep, how to use the right language, how to ensure you actually listen.”

* * *

For Momentum, the big question is: what happens next? After finding relevance fighting for Corbyn in two leadership battles, and now, two general elections, the group is keeping one eye on its next step. A major shift came earlier this year, and had a rippling effect at Labour’s annual conference on the Brighton seafront. Momentum began lobbying for policies that went beyond Corbyn’s existing blueprint for a socialist Britain, including a four-day working week, the abolition of immigration detention centres, and a green new deal focused on achieving zero carbon by 2030. “Radical and transformative policy can’t only come from the halls of Westminster,” a spokesperson declared at the time. “It must come from Labour’s half a million members.”

Attempting to reinvigorate activists demoralised by Labour’s triangulation on Brexit, for the first time the group found itself publicly demanding a more radical programme for government than the one on offer. After all, one of its founding values was to support Corbyn’s left-wing policy agenda, not just the leader himself. It could also be viewed as the organisation re-establishing itself for one of two scenarios: a post-Corbyn Labour Party, or a Corbyn government.

For the latter, it is how to remain relevant having played a major role in installing one of the most left-wing administrations in Downing Street in British political history. It is clear there is no intention of winding down when this ultimate goal has been achieved. Instead, it will be about ensuring there is “demonstrable public support” for key elements in Labour’s “boldest and most ambitious programme since 1945”, such as the green new deal that Lansman believes will come under attack in parliament from the Conservatives and opposition parties. “I don’t have any doubt that Jeremy and John McDonnell are committed to that programme,” he says. “I think that doesn’t mean to say no pressure is required to ensure that the Labour Party as a whole sticks with its guns.”

Jones believes that if Labour forms a government after the snap election, “all hell would break lose from an establishment which is not very happy at all with that form of government”. He adds that Momentum’s role in this scenario would be to continue mobilising in communities, but also putting pressure on a Labour administration.

He says: “It shouldn’t just be an auxiliary wing of the Labour leadership. Already you’ve seen Momentum put pressure on the Labour leadership to shifting position on anything from the rights of migrants, which the Labour leadership have been quite depressing on since the referendum, and other issues like being more radical on the climate emergency.

“In government, Momentum should put pressure on the Labour leadership if it wasn’t to fulfil radical promises – it’s not there to be a Corbyn fanclub, it’s there to fight for socialist policies.”

But as Laura Parker, a former private secretary to the Labour leader and now national coordinator at Momentum, said at the beginning of the campaign: the party has a “mountain to climb” to achieve victory and deprive Johnson of a majority Conservative government. Lansman points to Labour’s recent improvement in the polls – a BMG survey for The Independent showed the party had cut the Conservative lead to just six points at the weekend. He believes a “great number of seats” are within target if Labour’s position improves, but on the prospect of a majority Labour government he admits: “That is obviously a lower chance than us being in some kind of minority government, but I think there’s an excellent chance of that and that is absolutely what we’re working for. That’s why we’re targeting offensively, because we want to win, and we think we can win.”

For the former scenario, however, it is how Momentum reasserts itself if Corbyn is defeated at the first December general election for almost a century. According to last week’s polling model by YouGov, which accurately predicted the outcome of the 2017 election, Labour is on course for its worst election result since 1983 when Michael Foot was at the helm of the party. If it is proved correct a second time, Corbyn would be under immense pressure to resign.

Momentum will probably play a key role in the resulting leadership contest, and if it decides to throw its powerful caucus behind a left-wing candidate, that individual will have a considerable chance of victory. But for now, at least, Lansman is unwilling to entertain life after Corbyn. “We’re focused on winning, we’re not focused on losing, or losing badly,” he says. “I think Jeremy should step down when he wants to step down. I think that is matter to be considered – these are matters to be considered when we, after the election. I don’t expect there actually be a very rapid decision. There will only be one week before Christmas at that point. I’m expecting him to be putting a cabinet together in that week.”

But one thing is clear: there will be no closing down of operations at Momentum should Labour lose the election and Corbyn decide it is time to step aside. “The wilderness years are over whatever the outcome of this election,” Lansman adds. It’s a reference to his own return from political irrelevance and the left’s position on the fringes of the Labour movement. “The Labour Party has shifted big time. Actually British politics has shifted against austerity big time. That was achieved actually as soon as Jeremy won. Theresa May was already trying to park her tanks on our lawn, claiming that austerity was over,” he says. “I’m not going back to the wilderness, no, absolutely. I and Momentum are here for the long run.

“We are here for the long run, and we will deal with whatever the result of the election is.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks