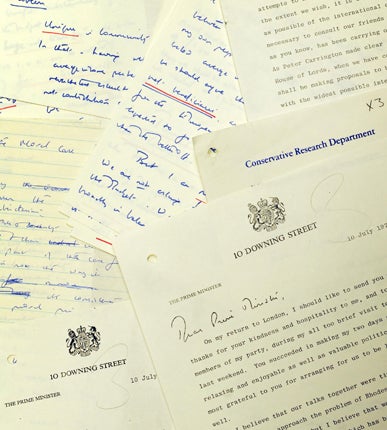

Memo from Margaret: a lesson on how to take power

Papers revealing the minutiae of the 1979 Downing Street handover have been released. David Cameron, take note

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.More than 30 years have passed since a defeated Labour Prime Minister handed over the tenancy of 10 Downing Street to a Conservative. Last time, the victor was, of course, Margaret Thatcher, a figure so intriguing and divisive that she still exerts a fascination, decades after her fall from power.

Today is a good day for Thatcher obsessives, as a huge bundle of documents about her time in office are now available online for the first time, on the website of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation. As David Cameron's people get ready for what they hope will be repeat of the 1979 result, they might want to study these documents for the light they shed on small but important problems that crop up as power shifts from one party to another.

There are good handovers and bad. The documents reveal that 1970 and 1974, when the Conservatives and Labour alternated in government, were bad handovers, because Edward Heath's staff, headed by the future foreign secretary Douglas Hurd, did not trust Harold Wilson's team, with the prickly Lady Falkender in charge.

Mrs Thatcher's people were determined that 1979 should be a civilised handover. Her political secretary, Richard Ryder, even suggested that she should tell her Labour predecessor, James Callaghan, that he could keep Chequers for the time being, if he wanted it. She agreed, adding the comment "no hurry" in the margin of Mr Ryder's memo.

Mr Ryder was actually more worried about the civil service. "Douglas underlined how crucial it was that I should take hold of the Political Secretary's Office next to the Cabinet Room. It should not at any cost be grabbed by the Civil Service," he wrote, to which she added: "agreed".

Once ensconced in Downing Street, the staff had to sort out which of the thousands of demands on a Prime Minister's time were to be treated as priorities. This responsibility frequently fell upon Caroline Stephens, the personal secretary Mrs Thatcher had brought with her from Conservative Central Office, who later married Richard Ryder.

A week after the election, Miss Stephens was not at all pleased to come upon a letter to Mrs Thatcher from the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir David McNee, reminding her of a verbal promise she had made to take the salute at the police tattoo in Wembley the following October, on the Saturday evening after the Conservative annual conference in Blackpool, when she was likely to be exhausted. Miss Stephens sent a memo to her boss pleading with her not to go, on which Mrs Thatcher wrote: "Alas, I shall have to."

Four days later, Stephens tried again, this time supported by Thatcher's chief of staff, David Wolfson, who wrote in block capitals: "It just isn't possible." Still Mrs Thatcher would not budge, so after another four days had passed, Stephens had another go. "You were under the misapprehension that the week following the Party Conference is a light one," she wrote. "Please look at the attached diary. Can I refuse Sir David's invitation please?" At the foot of the note is Mrs Thatcher's final word on the matter: "I told him I would go."

Seemingly there was no detail too small to escape the new Prime Minister's attention. Her political strategist, Gordon Reece, made the mistake of thinking she would not be interested in the requests pouring into Conservative Central Office to use her image on postcards, tea towels, teacups and other paraphernalia, so he said no to all except one – a pint pot that was to have her image on one side, with the Duke of Wellington's on the other.

This got him into trouble. "How come? Without any reference to me?" Mrs Thatcher wrote in the margin of Mr Reece's memo, followed by a strict instruction that her image was not to appear on any form of merchandise.

As Mrs Thatcher sat down for dinner with one of the first visiting heads of state, the President of Colombia, she thought that the food was embarrassingly poor, so fired off a letter to Christopher Soames, one of her Cabinet ministers, telling him to sort out the Government Hospitality Fund.

Soames, who was Sir Winston Churchill's son-in-law, had the reputation of a man who knew how to dine well. Hence the backhanded compliment in Mrs Thatcher's memo, in which she said she was turning to him "not simply because GHF falls within your own area of responsibility but also because you are so well qualified by experience to appraise it with a critical eye."

As letters and telegrams of congratulation poured into Downing Street, her staff had to decide which ones merited a personal reply. Over a telegram from the comedian Peter Sellers, Miss Stephens wrote: "Do you want us to send you people like this or should they have the same reply as everyone else?"

The answer was that comedians and other such personalities had standardised typed letters. Personalised letters were reserved for really important people, such as the romantic novelist Barbara Cartland. Larry Lamb, editor of the Sun, did not even write; instead he sent Mrs Thatcher a congratulations card with a cartoon of Paddington Bear, for which he received a long thank you letter telling him that he must come in for a drink soon.

The Margaret Thatcher Foundation, based at Churchill College, Cambridge, is digitalising all of Margaret Thatcher's papers, public and private. Their website, margaretthatcher.org, already contains thousands of her speeches and public pronouncements. "Nothing on that scale has ever been attempted before that we can see – not for Reagan or Roosevelt, Mao or Mitterrand. Her career will be uniquely accessible," Chris Collins, from the Foundation, said yesterday.

The Thatcher archive: 'What I do for the party!'

*"The Prime Minister and Mr Denis Thatcher accept with very great pleasure the invitation to the Banquet to be given by President and Madame Soeharto..." – Letter to the Indonesian Ambassador from Mrs Thatcher's secretary, Caroline Stephens.

*"Caroline: What I do for the party! The same evening I was going to attend probably the best Rugby Football Dinner this year." – Note from Denis Thatcher, revealing his not so very great pleasure.

*"They are paid much too much – from our taxpayers' money! It looks like a real gravy train." – Mrs Thatcher's view of EU officials whose salaries were bigger than MPs'.

*"Morality is personal. There is no such thing as a collective conscience, collective gentleness, collective freedom." – Mrs Thatcher's private notes for a 1979 speech, eight years before her famous comment that there was "no such thing as society". The speechwriters left the remarks out.

*"It is most important that we get the structure and strategy right and I have already come to the conclusion that I shall have to make most of the important decisions myself." – Mrs Thatcher confides her thoughts in a handwritten letter to a friendly businessman, Alcon Copisarow.

*"Is it done to refuse? Can it be done nicely, or shall we plead no time?" – Mrs Thatcher ponders whether or not to accept the Freedom of the Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments