Behind Margaret Thatcher’s losing battle to stop Spycatcher publication

‘I am utterly shattered by the revelations in the book. The consequences of publication would be enormous,’ the then PM wrote in a handwritten note

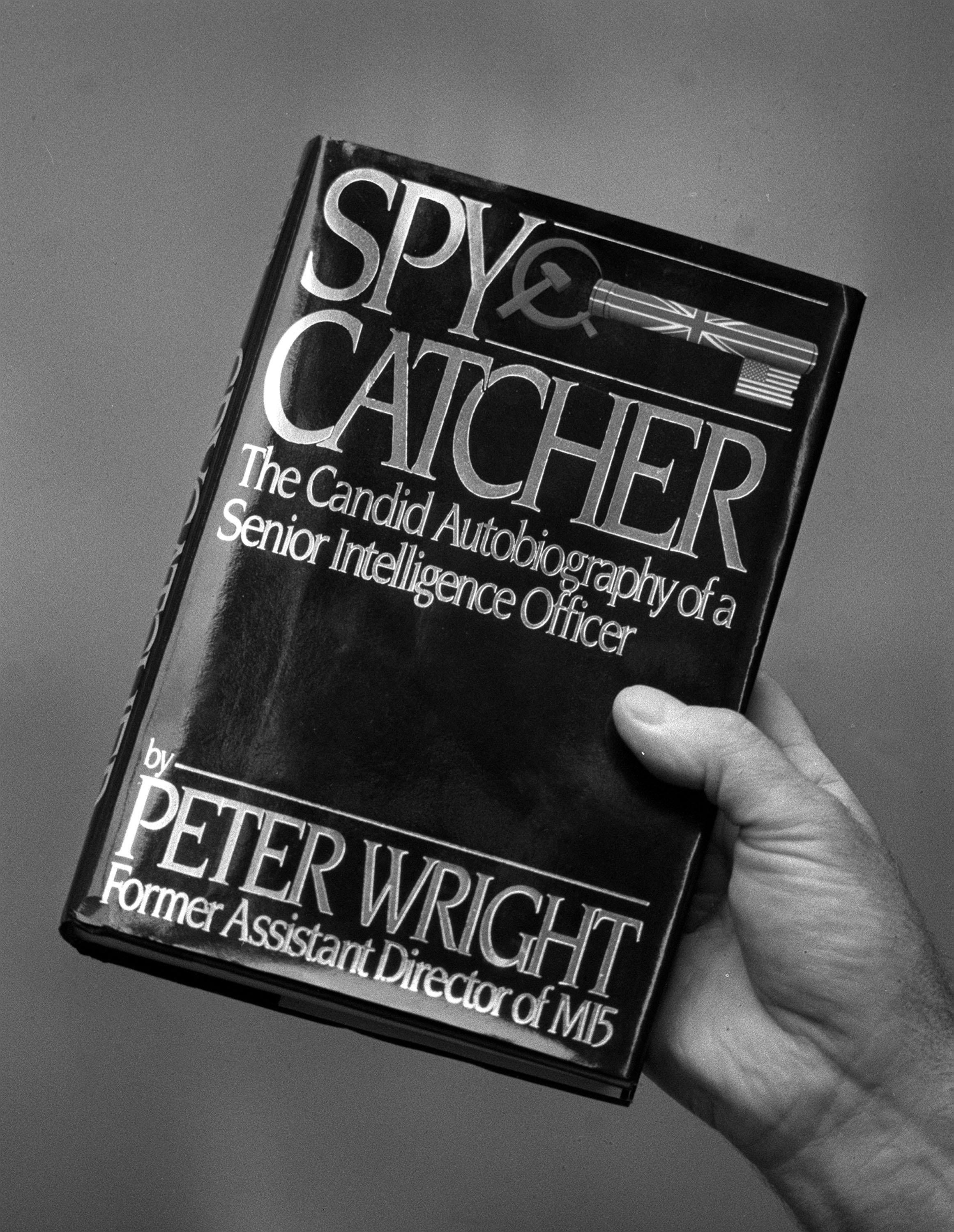

The increasingly desperate, and futile, attempts by Margaret Thatcher’s government to suppress Spycatcher, the memoir of a renegade ex-MI5 officer, are laid bare in official files made public for the first time.

Peter Wright caused a sensation in the 1980s, with his lurid allegations that a former head of the security service had been a Soviet mole and that M15 officers had plotted against Labour prime minister Harold Wilson because they believed he was in the pay of Moscow.

After ministers blocked the release of his book in the UK, his publishers turned to Australia, triggering the start of a lengthy international legal battle as the government fought to keep it off the shelves.

However, its efforts were effectively rendered meaningless by its publication in the United States where the first amendment right to free speech meant it was unable to stop it from becoming a runaway bestseller.

Nevertheless, papers released by the National Archives in Kew, west London, show ministers refused to give up on their attempts to prevent the British public from learning of its contents.

Pressure was put on the Commons speaker to stop debate among MPs, public libraries were threatened with legal action if they stocked it while ministers considered invoking emergency wartime powers to prevent people from bringing copies into the UK.

Mr Wright’s most sensational claims were largely discredited: an official investigation had already concluded there was no evidence Sir Roger Hollis, who was MI5 director general in the 1950s and 1960s, had been a Soviet agent while Mr Wright himself admitted there was no plot against Mr Wilson.

However, what seemed to many to be the government’s heavy handling of the case ensured it became a cause celebre among campaigners for free speech, leading to a humiliating defeat in the Australian courts.

Mr Wright’s claims had already been the subject of one book, Their Trade Is Treachery by journalist Chapman Pincher, which had been published uncontested.

But while ministers had suspected he had been the unnamed source for that volume, when in 1985 he attempted to publish openly under his own name, Mrs Thatcher was adamant they had to act.

“I am utterly shattered by the revelations in the book. The consequences of publication would be enormous,” she wrote in a handwritten note.

Right from the start, their efforts were flawed, with an injunction they obtained blocking publication in England and Wales but not Scotland.

Mrs Thatcher’s private secretary Nigel Wicks said that, while London-based newspapers had felt unable to report details of the legal proceedings taking place in Australia, The Scotsman had published a “substantial” account.

“There is therefore much talk in the press about one law for the English, another for the Scots etc,” he said.

As travellers returning from the US began arriving back in the UK with copies during the summer of 1987, ministers scrambled to see if they could impose an import ban.

Trade and industry secretary Lord Young of Graffham advised that, while it was “technically possible” using emergency powers passed at the outbreak of the Second World War, it was unlikely to be effective.

“The use of these powers in the Spycatcher case could well be challenged,” he warned.

“I am also advised that, even if the book were banned, it would not in practice be possible to catch all copies of the book brought in from the United States either by mail or by individual travellers.”

Meanwhile, arts minister Richard Luce said that an international conference of librarians, being attended by several Americans, could see a further influx of books from the US.

“We know that at least one British librarian has arranged to receive a copy of Spycatcher from a colleague for his library,” he wrote.

At Westminster, solicitor general Sir Nicholas Lyell expressed frustration that Commons speaker Bernard Weatherill was refusing to curtail debate among MPs, on the grounds the case was sub judice, in the way ministers wanted.

“The speaker expressed concern about the ‘credibility’ of his position given that ‘practically everyone he met’ had already read the book,” Sir Nicholas complained.

“I replied that most people in the country had not read the book and that every newspaper, bookshop and library was at risk of contempt proceedings if they published extracts, quoted from, or sold or stocked the book.”

There was particular concern that HM Stationery Office was importing copies of the official journal of the European Community, including proceedings of the European parliament, after Labour MEPs read extracts from the book into the record.

Mr Wicks told the prime minister they could look “very foolish indeed” if a government agency was found to be importing the very material it was trying to block.

She agreed, noting: “We must do everything we can to ensure that one hand of government does not distribute what the other hand is trying to stop.”

Home secretary Douglas Hurd, however, warned the UK could be in breach of its European treaty obligations if it tried to stop them.

As an alternative he suggested that, with HMSO only importing 10 copies, they could arrange for a government department to acquire the lot and then “procrastinate” if a member of the public wanted to buy one.

He added however that “such an elaborate stratagem would run the risk of seeming ridiculous”.

There was however one dissenting voice in No 10. Bernard Ingham, Mrs Thatcher’s press secretary, warned that the government’s position was “riddled with self-delusion”.

“I consider that a far more effective remedy would be for the secret services (who have, after all, largely got themselves into this mess) publicly to shut up, and secretly to grit their teeth, pull themselves together and get on with it,” he wrote.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks