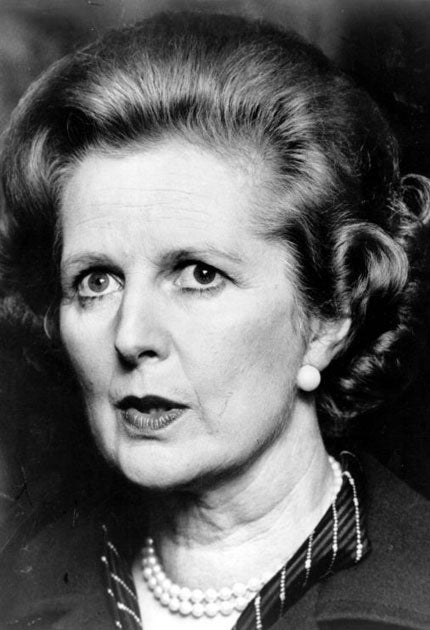

Margaret Thatcher: First among unequals

Britain's only female premier is back in vogue. Yet while her successors borrow her ideas, they'll never match Margaret Thatcher's audacity, says Andy McSmith

Sometimes it seems that Margaret Thatcher never went away. In five months, we will be marking the 20th anniversary of her fall from power, an event which had some people weeping in distress and others cheering in the streets. Yet, while other ex-prime ministers slip quietly out of the collective memory, her reputation refuses to fade.

Young people who were not born when she left office know who she was, have a strong idea of what she stood for, and hold pronounced views on whether she was good or bad for Britain. Each of her successors has paid homage to her. It greatly distressed John Major that she never rated him as a successor. Tony Blair invited her to revisit Downing Street in 1998. She was invited back by Gordon Brown only two months into his premiership.

Two weeks ago, she back there yet again. Looking frail now, dressed a powder blue coat, the 84-year-old Baroness waved to the cameras from the doorstep of No 10 before being gently helped inside by a successor who is young enough to be her grandson.

Even Sarah Palin wants a share of that Thatcher glory. Alaska's favourite hockey mom has arranged a visit to the UK, and announced on her Facebook page last week that she would love to meet "the Iron Lady", who is "one of my political heroines".

The dramatists and novelists have not tired of her either. In 2008, BBC4 showed The Long Walk to Finchley, a fictionalised account of her early career, starring Andrea Riseborough. BBC2 followed that last year with a dramatisation of her last days in power, with Lindsay Duncan playing the lead.

A few names from the Thatcher era have been brought back into the news by the return of the Conservatives to government, such as Lord Young of Graffham, once one of her favourites. She said of him that while other ministers brought her problems, he brought solutions. After 21 years out of office, Lord Young is running a Government inquiry into health and safety regulations.

More importantly, Mrs Thatcher's long shadow hung over the drastic budget introduced by George Osborne last week. After the experience of the 1930s, it was accepted orthodoxy that governments do not cut public spending in a recession, but use borrowed money to stimulate growth. Mrs Thatcher was the first post-war leader to do the opposite, 30 years ago.

That worked for Mrs Thatcher then, in that it kept her in power for more than a decade, though at the cost of driving unemployment above three million and devastating the economic base of large parts of the country. David Cameron, George Osborne and Nick Clegg now hope it will work for them.

But there is no prospect of the lady herself making a comeback. She is now too "fragile", as those who know her tactfully put it. In March 2002, after she had suffered a series of strokes, her doctors warned her not to risk any more speeches or public appearances that might put under strain and induce another stroke. In June 2003, she took a heavy emotional knock when Denis Thatcher died.

Though she puts in an occasional appearance in the House of Lords, she has not spoken in the chamber since 6 July 1999. Her last speech there was not her finest. It was a eulogy to that blood-soaked dictator Augusto Pinochet of Chile, who, according to Baroness Thatcher, was "being victimised because the organised international Left are bent on revenge".

It was indicative of Mrs Thatcher's thought processes that she saw a military dictator who overthrew an elected President as a "long-standing friend of Britain" while all the time that Nelson Mandela was in prison he was, in her eyes, the head of a terrorist organisation.

But the forthright way that she gave voice to her right-wing opinions are a large part of her lasting fascination. We are so accustomed to being smothered with bland sentiments by politicians that we have almost forgotten what it was like to have a prime minister who told it like she saw it.

As the Government laid out its drastic economic strategy last week, its leading ministers were at pains to emphasise, or exaggerate, how "fair" they are being, how the rich will suffer along with the poor, that we are "all in it together".

It is so de rigueur for ministers to be champions of equality that the Home Secretary, Theresa May, is also, by the way, the Minister for Women and Equalities and her ministerial team includes a Minister for Equalities in Lynne Featherstone. Whether the modern Conservatives truly believe in equality or not, they want to be seen to be for it.

But Mrs Thatcher did not pretend to place any value on equality. On this question, she set out her stall in a speech in the USA just a few months she had been elected leader of the Conservative Party in 1975.

"The pursuit of equality itself is a mirage," she said. "Opportunity means nothing unless it includes the right to be unequal and of freedom to be different. One of the reasons why we value individuals is not because they're all the same but because they're all different ... Let our children grow tall and some taller than others, if they have the ability in them to do so."

You do not need to agree with a word of this to be impressed by the clarity and certainty of the argument she presented. She was a woman with courage in her convictions.

One of the pleasures of researching the Thatcher years is tracing back to the original source the sayings that are attributed to her. Too often, politicians turn out – disappointingly – not to have said what they are alleged to have said, and what you rather wish they had said. Denis Healey never promised to "squeeze the rich until the pips squeak". Nor did Norman Tebbit ever remark that "nobody with a conscience votes Conservative" or tell the unemployed to get "on yer bike" to look for work.

But Margaret Thatcher really said "there is no such thing as society", in an interview with a woman's magazine. She was making a serious if highly contentious point about self-reliance and the welfare state. Just before the Falklands conflict turned bloody, she actually stood on the steps of Downing Street and ordered the journalists there to "rejoice". On her birth of her first grandchild, she truly did step forth to announce "we are a grandmother". These days, no one reaches the front rank of politics until they have been carefully coached not to say anything so memorable.

The other, obvious element that makes up the Thatcher legend is that this was a woman who fought her way to the top in a world controlled by men. When she was elected leader of the Conservative party, there were just 27 women MPs out of 623. On the Conservative side, there were seven women and 270 men.

To quote Sarah Palin's Facebook entry: "Baroness Thatcher's life and career serve as a blueprint for overcoming the odds and challenging the 'status quo'. She started life as a grocer's daughter from Grantham and rose to become Prime Minister – all by her own merit and hard work. I cherish her example and will always count her as one of my role models."

She achieved that, moreover, without being the stereotype Conservative battleaxe. She liked to be complimented on her femininity and, extraordinary as it may seem, there were men who found her devastatingly sexy. The novelist Kingsley Amis thought her "one of the most beautiful women I have ever met", and had recurring dreams about her. Alan Clark and Woodrow Wyatt also lusted after her. A Tory MP, Sir Nicholas Fairbairn, once told the Commons that he had witnessed a drunken guest at a reception hosted by the Lord High Commissioner of the Church of Scotland telling Mrs Thatcher how he fancied her, to which she replied, with her unusual tin ear for double meanings: "Quite right. You have very good taste but I just do not think you would make it at the moment."

On the down side, there was her wilful blindness to the human consequences of her actions. Like the current administration, she came to power, in 1979, at a time of economic crisis, and took remedial action which she knew would lead to mass unemployment an immense hardship for many thousands of people. But if she ever cared about the casualties, it did not show. During the miners' strike, in which the miners were after all fighting to hold on to their dignity and their way of life, she really did describe them as "the enemy within". If she meant those words to apply narrowly to the leaders of the national Union of Mineworkers rather than every striking miner, she did not make it clear.

Visiting the north east of England in 1987, a region where unemployment was higher than anywhere else in England, she replied to a question on the subject by delivering a homily on "moaning minnies". After CS gas had been used on the British mainland for the first time ever, to disperse rioters in Toxteth, Liverpool, in July 1981, even a hard-nosed Conservative such as Michael Heseltine grasped that this was partly a consequence of government policy and required government action, but she could not see it.

"I had been told that some of the young people got into trouble through boredom and not having enough to do," she wrote in her memoirs. "But you had only to look at the grounds around those houses with the grass untended, some of it waist high, and the litter, to see that this was a false analysis. They had plenty of constructive things to do if they wanted. Instead, I asked myself how people could live in such circumstances without trying to clear up the mess."

She was the Marmite Prime Minister. She leaves a strong taste that you love or you hate. On a purely personal note, all my life I have loathed Marmite.

Andy McSmith's book, 'No Such Thing as Society, A History of Britain in the 1980s', will be published by Constable & Robinson in September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks