Margaret Thatcher aides 'buried' plan to make her condemn apartheid

National Archives documents seemingly reveal how plan to defuse boycott of 1986 Commonwealth Games was thwarted

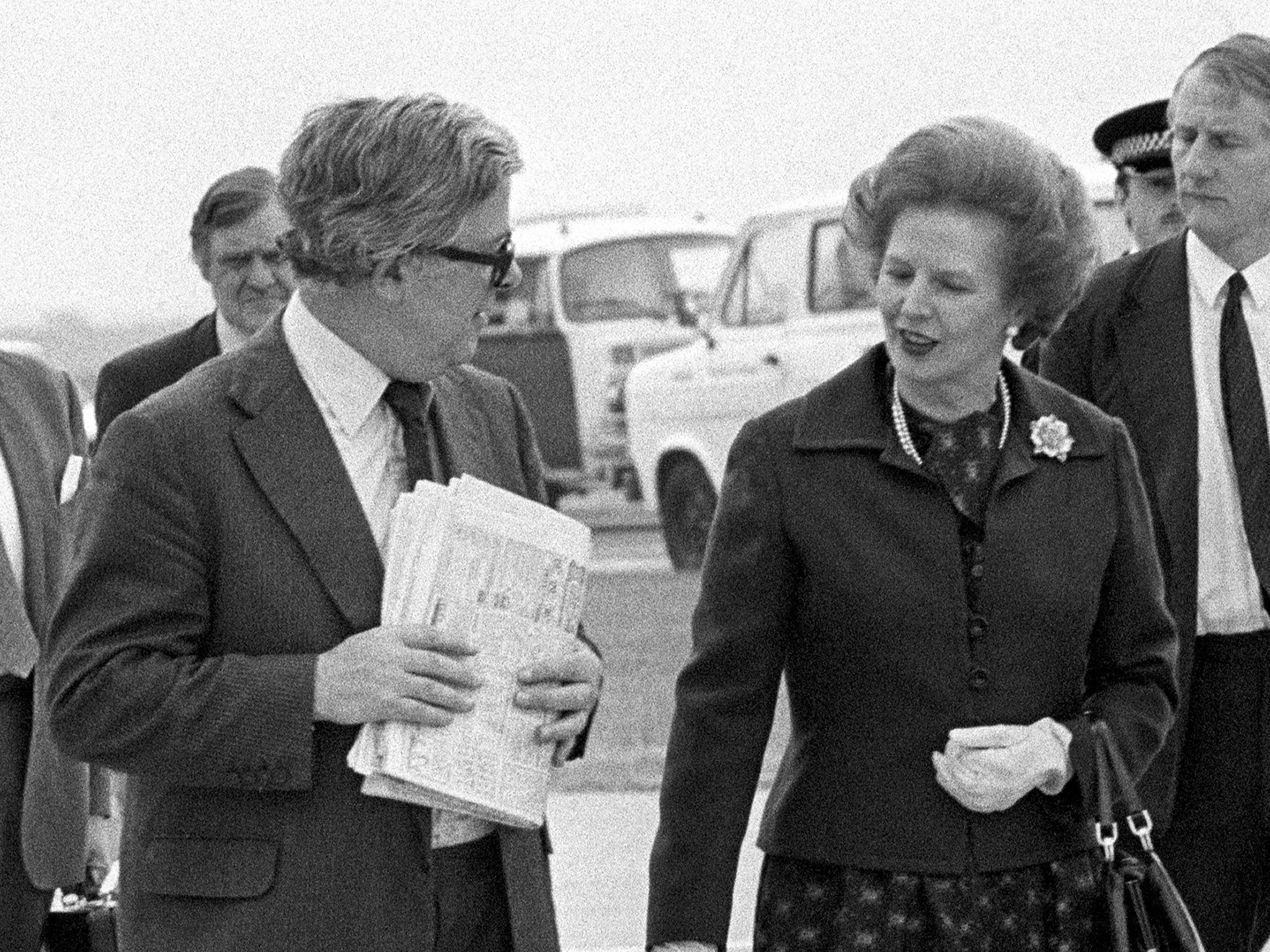

An attempt by a senior member of Margaret Thatcher’s government to defuse the row over apartheid, which led to a mass boycott of the 1986 Commonwealth Games, was ordered to be “buried” by her closest aides.

The decision by 32 of 59 eligible countries to boycott the £15m event in Edinburgh over Britain’s refusal to impose sanctions and sever sporting links with apartheid South Africa caused a crisis for the Conservative government and left the organisers of the Edinburgh games with a deficit of nearly £4m.

But documents released at The National Archives in Kew, west London, reveal how a plan put forward by Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe to defuse the boycott by persuading Mrs Thatcher to publicly condemn apartheid was seemingly thwarted by Downing Street officials, including her private secretary Charles Powell.

Following the withdrawal of several countries, including Nigeria and Ghana, less than a month before the Edinburgh games were due to open in late July, Sir Geoffrey’s aides wrote to Number 10 suggesting that a speech by Mrs Thatcher unequivocally denigrating South Africa’s racist system might stop the trickle of withdrawals from turning into a cascade.

With South Africa under a state of emergency amid increasing repression and violence, Britain was under intense pressure by the summer of 1986 to join international efforts to isolate the apartheid regime using economic sanctions, as well as ending sporting links through events such as cricket and rugby tours.

In a letter to Downing Street in early July, the Foreign Office said that Sir Geoffrey, a former Chancellor and close ally of Mrs Thatcher who would eventually play a key role in forcing her resignation in 1990, was “seriously concerned” at the withdrawal of Malaysia and the Bahamas.

Diplomats asked for Mrs Thatcher to retrieve the situation by using Question Time in the House of Commons to underline her opposition to apartheid and end the impression that Britain was South Africa’s prime cheerleader on the international stage.

The letter said: “As the Prime Minister knows, in Sir Geoffrey’s view the problem is that, because of our vigorous and persistent public opposition to comprehensive economic sanctions, many Commonwealth leaders now see us as the main defender of the South African government and of apartheid.

“In order to start putting that right, the Foreign Secretary included a strong attack on apartheid in his Commons speech this afternoon. But he believes it would also be extremely helpful if the Prime Minister could reinforce the message… If she took that opportunity herself to deliver a strong attack on apartheid the addition of her authority would greatly help our efforts to stem the tide of withdrawals.”

The Foreign Secretary added suggestions as to what Mrs Thatcher could say, including a statement that would “reiterate my total rejection of apartheid and all it stands for”.

But while Sir Geoffrey’s aims may have been noblethey did not meet with a warm reception inside Downing Street.

Notes written on top of the Foreign Office letter suggest that officials did not want Mrs Thatcher to be able to give too much consideration to the proposals. One instruction read: “Please bury deep.” A further note added: “CDP [Charles Powell] to bury.”

The failure to limit the boycott led to a chain reaction, with more than half of eligible countries staying away, leaving its organising committee with a £3.8m deficit.

The documents show that the shortfall led to a further round of brinkmanship, this time between Mrs Thatcher and Robert Maxwell, the owner of the Daily Mirror, who was belatedly brought in as chairman of the organising committee and handed the task of recouping the losses.

In a series of letters between the Prime Minister and the flamboyant Labour-supporting businessman, Mr Maxwell sought to press the Tory government to reverse its refusal to offer any public money to fund the Edinburgh Games and stump up £1m to pay off its creditors.

Painting himself with characteristic shyness as the hero of the hour, Mr Maxwell wrote: “The effect of the boycott of the Games, by over 32 countries, has been catastrophic… There has been virtually no opportunity at this late stage to curtail expenditure. I accepted this onerous task simply because [of] the alternative as was put to me of the immediate appointment of a Receiver with the national humiliation that this would bring to both Scotland and the UK.”

But despite the repeated pleas of the mogul and others, including then Scottish Secretary Malcolm Rifkind, to loosen the purse strings, Mrs Thatcher remained steadfast, telling Mr Maxwell that “if the Government were to go back now they would never be believed on other matters”.

Eventually the deficit was resolved with the help of a £1.3m donation from a billionaire Japanese philanthropist and acquaintance of Mr Maxwell, Ryoichi Sasakawa.

But the difficulties generated by the Games did not end there. After Mrs Thatcher agreed to write a letter of thanks to the businessman, the Foreign Office revealed a dark side to Mr Sasakawa, who had been arrested as a suspected war criminal after the Second World War and was known to have extremist sympathies – and be a possible gangster.

A memo said: “Despite his philanthropic and charitable activities around the world, Mr Sasakawa is perceived by many in Japan and abroad to be at best a supporter of extreme right-wing political views and at worst a major figure in the Japanese underworld.”

The documents show the letter was still sent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks