Is George Osborne really quite as clever as he thinks he is?

It was a gaffe-prone Budget, and his reputation has taken a hit. But the true significance is that it underscored the Chancellor's leadership ambitions

When he was an ambitious 23-year-old in the mid-1990s, one of George Osborne's jobs as head of the Conservative Research Department's political section was to prepare cabinet ministers for appearances on Question Time.

The young Osborne was brilliant at it: coaching members of John Major's top team on what questions would come up on the programme, and how to move the story on. Not only did it get the rising star of the new Tory generation noticed by the Cabinet, including the then Home Secretary, Michael Howard, who years later would appoint him Shadow Chancellor, it also showed off Osborne's sharpest skill – predicting the next day's headlines.

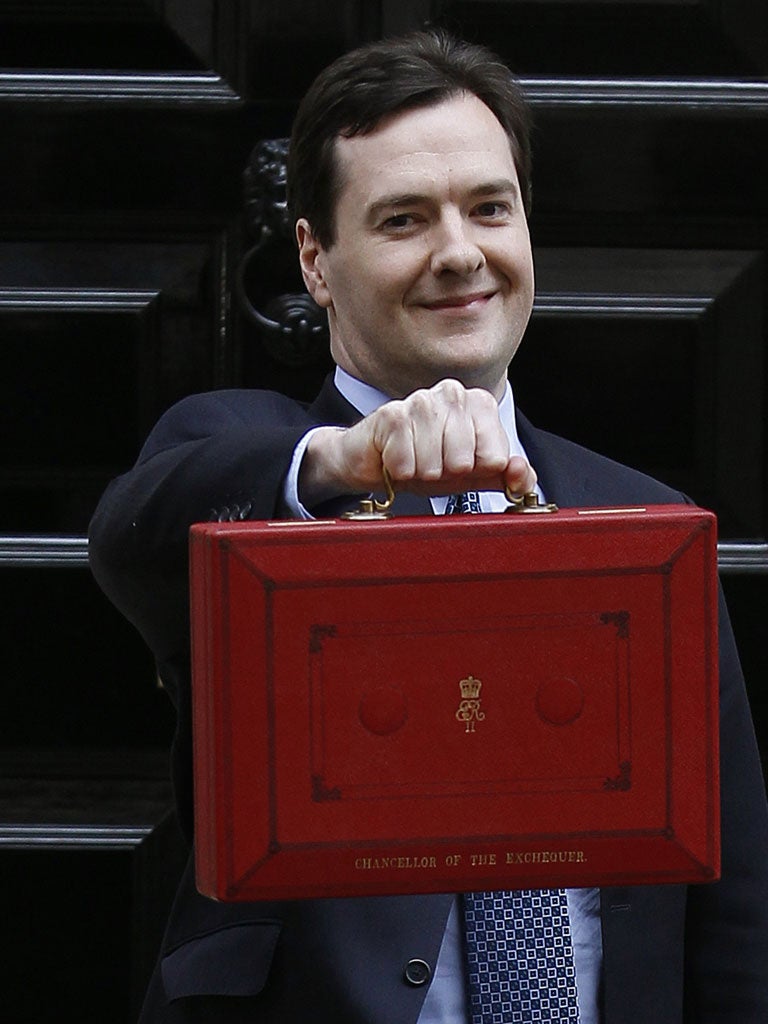

This famed ability for "war-gaming" politics, or thinking like a chess grand master, as one loyal MP describes it, which has carried Osborne from the bottom of the Tory party to the top of Government, appeared to desert the Chancellor of the Exchequer on Wednesday. After days of leaks, everyone expected Osborne to pull a rabbit out of the hat – an expectation fuelled by a broad smirk as he appeared on the steps of No 11 Downing St, Budget Box aloft. "George loves a rabbit," said one friend as the nation awaited Osborne's statement. Yet the only surprise was a raid on the personal allowances of pensioners – or the "granny tax", as it quickly became known – which was splashed all over the next day's papers. Even Osborne's closest allies admit that it was an error not to foresee the ferocity of the reaction to the cuts to the age-related allowance.

So where does this leave Osborne's credibility as the man with the biggest political brain in Westminster? And, more importantly, what does it do to his ambitions to succeed David Cameron as Tory leader?

David Laws, the former Lib Dem chief secretary to the Treasury, who is close to Osborne, said on Thursday that the Chancellor had proved he was a "grand strategist" who had "pulled off quite a political coup". But not all coalition members and MPs agree; his strategic gaffes have caused lasting damage. Chief among them, in 2007, was recommending Andy Coulson to Cameron as his director of communications, a decision that haunts the Prime Minister to this day.

Another serious error, Osborne's critics complain, was persuading Cameron to agree to a series of televised leadership debates during the 2010 election, which gave too much exposure to Nick Clegg and in the end cost the Tories an outright victory. Tory MPs still use this against him. One says: "If Osborne is such a great strategist, why didn't we win the 2010 election, which he masterminded?"

Osborne is acutely aware of this. Unlike Cameron and Steve Hilton, he was too young to have worked on the Tories' successful 1992 election. By the time of Osborne's first campaign, in 1997, little could stop Tony Blair. So, while Cameron can claim to have worked on a successful campaign, Osborne cannot.

There have been other cock-ups: trying to take on Peter Mandelson – the headmaster of the dark arts – over Yachtgate in 2008. And, critics suggest, perhaps he would have foreseen the granny-tax debacle had he not spent the week before Budget Day joining Cameron on his US state visit.

But supporters point to his triumphs which, they say, have been much more important to the success of today's Tory party than his failures. When Gordon Brown called off a snap election in October 2007, many saw it as Cameron's impressive "no-notes speech" to his party's conference that spooked the Labour PM. But, in reality, it was Osborne's promise to lift the inheritance tax threshold to £1m that forced Brown into retreat.

Osborne has also managed to install himself as the chief executive of the Government, as Tim Montgomerie of ConservativeHome said yesterday, taking the hands-on role while leaving the chairmanship to Cameron.

Three of the most powerful Tories besides Cameron – Osborne, Hilton and Boris Johnson – see their politics as more radical and "virile", as Johnson's biographer Andrew Gimson describes it. While Cameron plays it safe by appealing to the centre ground, the other three want the Prime Minister to use his first term to go further, faster, higher. And with Hilton on his way out of No 10 to California, the Chancellor's power is even stronger.

Which brings us to Osborne's leadership ambitions. Many expect Cameron to step aside in 2018, after 13 years as leader, giving his successor enough of a run-up to the 2020 election. Cameron recognises his old friend as the leading candidate, and Wednesday 21 March could mark the unofficial start of Osborne's 2018 leadership campaign.

While the "granny-tax" raid was the main story for most papers on Thursday, including the Tory-supporting Daily Mail and Daily Telegraph, The Times, edited by Osborne's long-term friend James Harding, splashed on the Chancellor's 50p tax-rate "gamble". This was the headline Osborne wanted and the story he believes matters more, years down the line, because, he says, it is the key to economic growth.

Osborne made a tactical error in not explaining the granny tax properly, but the bigger picture is that, to him, it doesn't matter upsetting Telegraph-reading pensioners of Godalming, who would still vote Tory in any election.

Cutting the 50p rate appeals to the 2010 intake of Tory MPs, many of them on the "new right", including members of the Free Enterprise Group, who are emerging as the most influential backbench group of Conservatives, and hold the key to the next leadership poll.

On Wednesday afternoon, one of their number was spotted defending the "granny tax" to a Tory grandee, who complained that it was punishing Tory heartlands. Osborne's aides let it be known that he wanted 50p to be cut to 40p, but that Cameron had persuaded him to leave it at 45p. In Budget negotiations with the Lib Dems, Osborne's only concerns were cutting the 50p rate and softening child benefit for higher earners.

A friend of Osborne, describing the UK economy as a Lamborghini, says: "There is no point in driving a Lamborghini as you would a Morris Minor, at 20 miles an hour. You need to get it out on the open road, at 90."

But Cameroons are uneasy. While they take comfort from signs of a more upbeat, pro-growth agenda, they still fear Osborne's influence. "We need to be clear there is something to be optimistic about, even if it is years off," says one minister. Osborne's relentless focus on 50p also exposes a weakness, that he cannot relate to the squeezed middle or the poorest in the way that Cameron has tried to.

Osborne's leadership chances rest on one crucial factor: whether the economy recovers enough by the middle of this decade. Cutting the 50p rate is a gamble, because the Treasury will lose £3bn unless the richest do what he asks, and stop avoiding paying tax.

If he wins his gamble, he could pull off a leadership victory in 2018. Yet, by then, the Tory party may want a leader from the new generation of MPs that was elected in 2010. Osborne is thinking six years ahead, but there are a lot of newspaper headlines to worry about between now and then.

The Chancellor's successes and setbacks

Hits:

Inheritance Tax As Gordon Brown mulled a snap election in October 2007, Osborne pledged to raise the inheritance tax threshold to £1m, forcing Brown to back off from a poll.

AV Referendum Osborne was the key Tory negotiator during coalition talks, agreeing to Lib Dem calls for a referendum on the Alternative Vote. He then pulled out all the stops for a "No" vote, and crushed Nick Clegg.

EU summit veto When Cameron brandished the UK's veto at the EU summit in Brussels in December, it was pure Osborne, who hoped to score big back home and win back the support of his Eurosceptic MPs. But it could cause lasting damage to Britain's international standing.

Misses:

Andy Coulson Osborne pressed for the former News of the World editor to become the Tories' spin chief. His presence in No 10 turned toxic and he was forced to quit last year. The PM faces questions on this at the Leveson inquiry.

Yachtgate In 2008, Osborne leaked details of Peter Mandelson "dripping poison" in his ear, when on holiday in Corfu, about Gordon Brown. Osborne emerged the loser when it was claimed he tried to solicit a donation from a Russian billionaire, Oleg Deripaska – a claim he denied.

2010 Election Even with an unpopular government and an economic crisis, the Tories failed to win outright. Among the errors, campaign mastermind Osborne talked Cameron into the TV leaders' debates.

Future of the coalition: Link with Tories will go on, top Lib Dem says

The coalition could continue beyond the next general election, with the Liberal Democrats tethered to Tory spending plans for a further two years, Danny Alexander, suggested yesterday.

The Chief Secretary to the Treasury, who wrote the Lib Dem 2010 manifesto, effectively ruled out a coalition with Labour by saying his party could only have different spending commitments from the Tories once the national deficit is eradicated.

In remarks that are likely to worry party grassroots, who already fear the Lib Dems are too closely aligned to the Tories, Mr Alexander told The Times: "The Liberal Democrats are an independent party ... But what we are committed to doing as a government ... is to maintain our fiscal consolidation until it's completed. That will involve making some choices about the first two years of the next Parliament. That doesn't preclude the Liberal Democrats from offering a different direction of public spending once that process is completed."

He added: "I'm absolutely certain the coalition will not just stay together until 2015 but continue to make big choices for this country."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks