EU referendum: How would leaving the EU work – and how would it affect you in the long term?

In the last of our three reports on the practical implications of a vote to leave the European Union, our Chief Political Commentator looks at what might happen in the long run

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The long-term outlook for Britain outside the EU is about three things: economics, economics and economics. Almost all economists who have pronounced on the subject say that our national income would be lower than if we stayed in the single market.

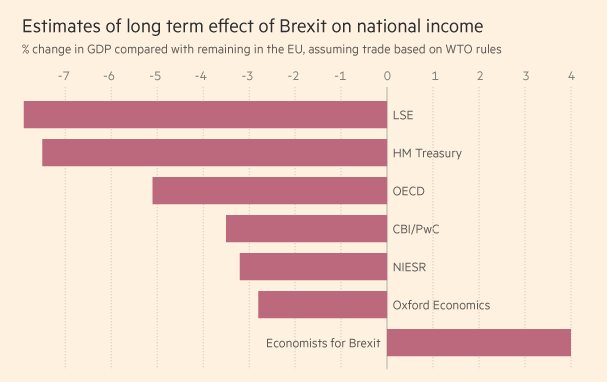

They do not say we would be poorer than we are now, but that we would be poorer than we would otherwise be. Estimates of the long-term effect range from 3 per cent of national income (Oxford Economics) to 8 per cent (London School of Economics).

There may be all sorts of good reasons for leaving the EU, but maximising national wealth is not one of them.

Wouldn’t a Brexit recession be short-lived?

We are not talking about the short-term effects of the disruption of Brexit. That would happen in two stages. First would be the immediate effect on confidence of a Leave vote: that would reflect expectations of lower growth in the long term, reducing economic activity immediately. Second would be the effects of Britain actually leaving the EU: the costs of tariffs on trade with the EU, and of new regulations now that we are responsible for our trade with the rest of the world.

But after that, once the economy has adjusted to those changes, the long-term effects of being outside the EU would still be acting as a brake on growth. There are three main reasons for this.

1. We would be trading less with the EU

Whatever our relations with the EU, we would not have tariff-free access to the single market, if we assume that Boris Johnson, or whoever is prime minister, sticks to the Leave campaign’s policy of refusing to allow Britain to be part of the free movement of EU workers.

2. We would attract less foreign investment

One of the reasons American, Chinese and Japanese companies choose to set up in Britain is that it gives them access to the EU single market. We would still have many attractions – the English language, lovely countryside, three-pin plugs – but we would be slightly less attractive than we were.

3. Our labour market would become less dynamic

At the moment, the British labour market is a world phenomenon. We are creating jobs at a record tilt. This is largely driven by immigration from the rest of the EU, but it is having a beneficial effect on British workers, driving growth and creating jobs for them too. Restricting immigration would create labour shortages, which might push up some wages in the short run, as Lord Rose, chairman of the Stronger In campaign, embarrassingly admitted three months ago.

In the long term, however, most economists say that a restricted labour market would restrict growth and any gains for groups of workers would be wiped out.

But these are the people who said we should join the euro

No, they are not. Most of the people who advocated adopting the euro were politicians. Economists were divided on the question. The Treasury, after all, concluded in 2003 that we should not join. Now, the Treasury, the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the IMF and the OECD all agree that the economic consequences of leaving the EU are negative.

This is not just guesswork. EU membership has been good for the British economy. Before we joined the EEC in 1973 we had the lowest average growth rate in the G7 – that’s us and the US, Japan, Germany, France, Italy and Canada. Since we joined we have had the highest.

Slower population growth

The main motive for leaving the EU, for most voters, is to reduce immigration. It seems reasonable to assume, therefore, that a post-Brexit government would exclude Britain from EU rules on freedom of movement, and try harder than the pre-Brexit government to restrict immigration from outside the EU as well.

Even so, it would be hard to reduce net immigration by much, as Clare Foges, David Cameron’s former speechwriter pointed out this week (pay wall). “When I worked at No 10 in 2010-15 – writing key speeches on immigration – I saw time and again how the Whitehall machine and various vested interests move to crush proposed immigration reforms.”

But population growth would be lower. So the effect on national income per head would be smaller than the 3-8 percentage points, and over time house prices might rise slightly less fast than they would otherwise rise.

Diminished global clout

Finally, there would be some non-economic effects of Brexit in the long term. If Scotland breaks away from the UK – possibly at the same time as England actually leaves the EU in around 2018 – the remaining kingdom of England, Wales and Northern Ireland would be smaller and even more lop-sided. Northern Ireland’s status probably wouldn’t change, but it would seem even more anomalous.

Britain might come under pressure to give up its permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (the other members are the US, Russia, China and France). This can be resisted, but over time, as new international arrangements are built, they will be built around the US, the EU, China and possibly India. Britain would probably come behind Japan and Russia in that global pecking order.

The first of our special reports, on the immediate impact of a Brexit vote, is here, and Andrew Grice’s second report, on the effect of Britain’s actual departure from the EU, is here

The EU referendum debate has so far been characterised by bias, distortion and exaggeration. So until 23 June we we’re running a series of question and answer features that explain the most important issues in a detailed, dispassionate way to help inform your decision.

What is Brexit and why are we having an EU referendum?

Does the UK need to take more control of its sovereignty?

Could the UK media swing the EU referendum one way or another?

Will the UK benefit from being released from EU laws?

Will we gain or lose rights by leaving the European Union?

Will Brexit mean that Europeans have to leave the UK?

Will leaving the EU lead to the break-up of the UK?

What will happen to immigration if there's Brexit?

Will Brexit make the UK more or less safe?

Will the UK benefit from being released from EU laws?

Will leaving the EU save taxpayers money and mean more money for the NHS?

What will Brexit mean for British tourists booking holidays in the EU?

Will Brexit help or damage the environment?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments