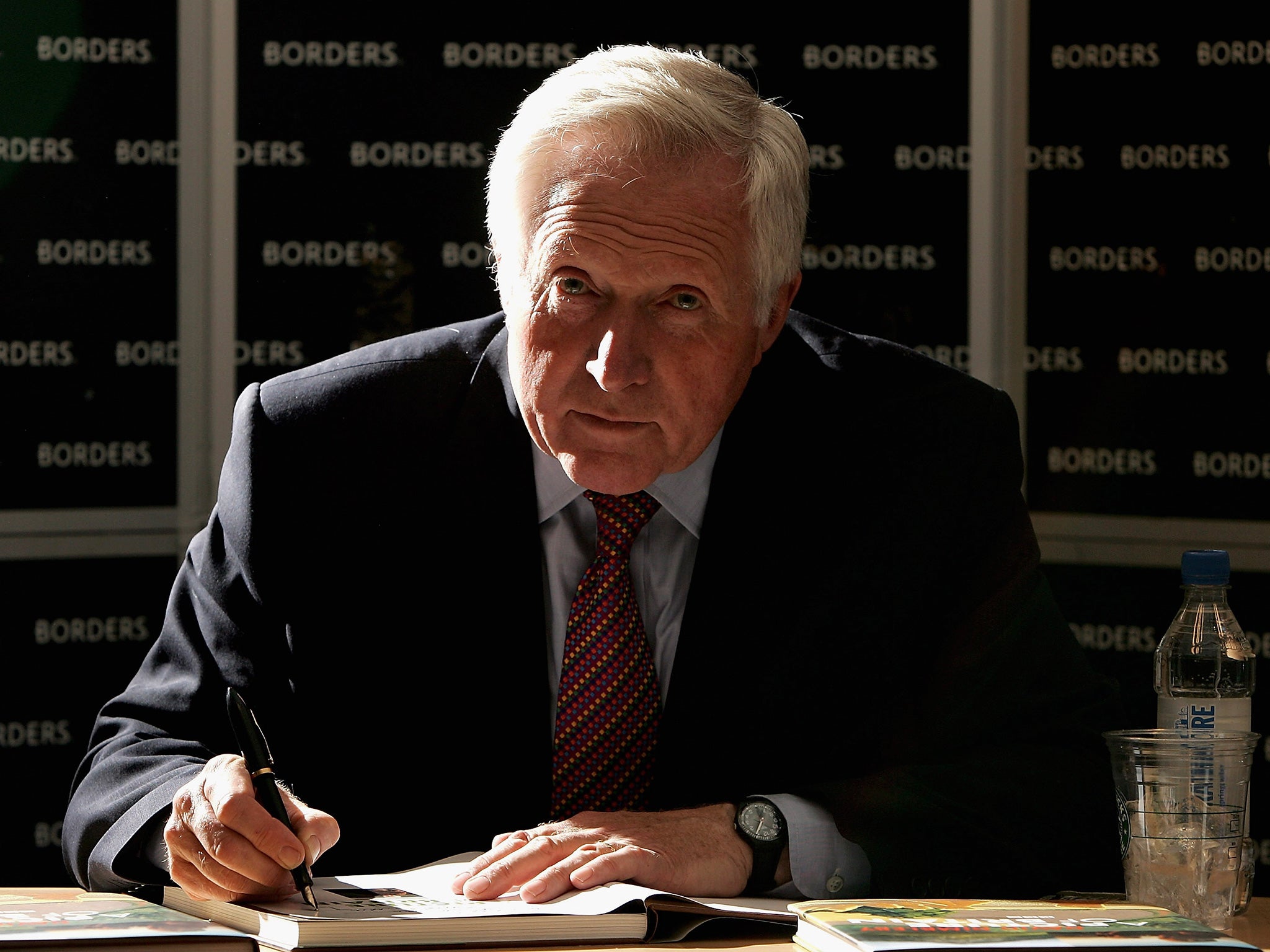

David Dimbleby profile: Britain's TV master of ceremonies on election night

Calm on the outside, the man once more guiding TV viewers through an election is driven by competitive spirit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Even if undecided voters were not swayed by the quizzing of the three main party leaders on Thursday night, they were left in no doubt why David Dimbleby remains in power.

In Leeds Town Hall, where he promised to preside over an “old-fashioned hustings”, a familiar gravitas and enthusiasm came to the fore. There was a lightness of touch that can summon a question from “the man under the big organ pipe” as easily as skewer Ed Miliband on forging an SNP deal. There was the rich, received pronunciation, the neatly combed white hair, dark suit and a tie of headache-inducing colours that tried too hard to reinforce his impartiality.

The political landscape may be splintering, but 50 years after his broadcaster father Richard’s untimely death, Dimbleby clings to the mantle of Voice of Nation in a very different age. He has done them all – commentating on the funerals of Diana, Princess of Wales and the Queen Mother, the state opening of Parliament, the dawning of the millennium – and every overnight general election broadcast since 1979. Jeremy Paxman, his competition for the Question Time gig 21 years ago – and a contender to succeed him should he ever choose to step down – once said that part of Britain’s unwritten constitution required a Dimbleby to cover all matters of national importance.

He has shown remarkable resistance to rewriting those rules. Even before the last election, with Huw Edwards waiting in the wings, Dimbleby put down a marker. “No, I don’t have any instinct to make way gracefully,” he said in 2010. “I shall be dragged kicking and screaming from the chair.”

Are you undecided about who to vote for on 7 May? Are you confused about what the parties stand for and what they are offering? Take this interactive quiz to help you decide who to vote for...

For a man so accomplished at asking questions, he is reluctant to answer them, saying little about the breakdown of his first marriage, the rivalry with his brother Jonathan, how much he is paid or which way he votes. As his last election-night marathon nears – the ninth time he has helmed coverage, surpassing the record set by the late Sir Alastair Burnet – one question is the most pointed of all. At the age of 76 – and I really must push you now, Mr Dimbleby – how long do you intend to carry on?

Born in Surrey in 1938, he was the eldest of four children in a family with newspaper ink in its veins. His appetite for journalism was fed early with family appearances on his father’s holiday TV shows. After attending private schools including Charterhouse, he edited the student magazine Isis while studying politics, philosophy and economics at Christ Church, Oxford. His devotion to the publication explains why he graduated with only a third-class degree. Decades before he swore off socialising with politicians, Dimbleby was also a member of the upper-crust Bullingdon dining club that is a breeding ground for future cabinet members.

He knew he had big shoes to fill. His father had been a huge figure in the early decades of television, reporting from Belsen and commentating on the Queen’s coronation, as well as the state funeral of Sir Winston Churchill. His son got an early clue of the celebrity that came with this brand of journalism, when, on a trip out from prep school in his dad’s chauffeured Rolls-Royce, the pair were ambushed by fans at an ice-cream parlour.

After university, his father preferred him to do something more serious such as becoming a judge or diplomat, but Dimbleby dived straight into television, freely admitting his surname helped him to get into the BBC in Bristol in 1960. From then on, he insists he got on under his own steam, although a short spell reporting for CBS in New York suggests he was eager to come out from under the shadow.

When his father died of cancer, Dimbleby was 27 and thrust into running the family firm, a local newspaper business that included the Richmond and Twickenham Times. It was a mixed blessing: he was routinely attacked by unions for paying journalists less than the minimum wage, but became independently wealthy when he sold to publisher Newsquest in 2001 for a reported £8m.

Finally, newspapers dropped the “son of Richard” tag around the time he was 40. By then, Dimbleby had earned a teacherly air presenting school quiz Top of the Form and taking over Panorama, another of his father’s vehicles. He long ago preferred to stick with the role of master of ceremonies that means he can call the shots, rather than become a Walter Cronkite-style news presenter, which he thinks would have quickly bored him. And it had to be high brow: the three months he spent on early-evening magazine programme Nationwide was the least enjoyable spell of his career.

Yet married to that, there is a mischievousness about him. Dimbleby shared the thrill of election-night coverage a decade ago, saying: “It’s fun. Innocent mischief, like a midnight feast in the dorm.” It is on nights like these that his competitive edge is on show too. His brother Jonathan, who forged a parallel career on ITV as well as hosting Radio 4’s debate Any Questions?, has often come up against him on the other channel. Dimbleby has made clear who must win the ratings battle.

His steady stewardship of Question Time was not a given. He was not the favourite to succeed Peter Sissons, but when Sue Lawley declined to chair a pilot show, Dimbleby’s on-screen enthusiasm outdid a disengaged Paxman.

There have been incidents of note, but nothing that a journalist wouldn’t be proud of: quizzing an angry Harold Wilson on how much he was paid to write his memoirs, riling Bill Clinton with repeated questions about Monica Lewinsky, prompting a public apology from the BBC for a labelling a London visit by Richard Nixon “a con”. By and large, without resorting to the maulings dished out by John Humphrys, his career has pushed regally on.

For a time, Dimbleby’s private life was far more interesting. In 1993 he left Josceline, his cookery-writer wife of 26 years, for Belinda Giles, a TV producer 20 years his junior. With Josceline, he has three children: Liza, an artist, Henry, who founded the fast-food chain Leon, and Kate, a jazz singer. Now he lives on a farm in Polegate, East Sussex, with Belinda and their son Fred, 16, where they keep cattle and relax by walking, drawing, sailing and playing piano.

But if his personal circumstances have changed, the BBC has been a constant. He might have risen higher in the corporation, but despite encouragement from the then-chairman Sir Marmaduke Hussey to apply to become director-general in 1987, he was beaten to the post by Michael Checkland. Dimbleby always thought he would have made a better chairman, but that opportunity, in 2001 and 2004, eluded him too. His affection for the corporation is manifest, he has described the BBC as “the most important institution in Britain” and has defended it from charges of dumbing down. But he is one of few on-air figures allowed to criticise freely, making known his dismay at the decision to move Question Time’s editorial base to Glasgow.

In a nod to the future, Dimbleby has already begun to share duties. He sat out the local election results two years ago, the first one he has missed since the early 1970s. While he talked the nation through Lady Thatcher’s funeral, it was Edwards who bagged the wedding of William and Kate as well as the Scottish independence vote last September. Next week, Edwards takes over broadcasting duties on Friday morning, when the first manoeuvres of a hung parliament are expected, and becomes the lead presenter for the corporation’s future election coverage. But Dimbleby will return on Friday night with a special post-election edition of Question Time. For now, at least, Britain’s veteran interrogator-in-chief gets the last word.

A Life in Brief

Born: 28 October 1938, Surrey.

Family: His father Richard was a broadcaster and his mother Dilys a journalist. He has three children with first wife Josceline and a son with his second wife Belinda.

Education: Glengorse School and Charterhouse School. PPE graduate, Christ Church, Oxford.

Career: Joined BBC in 1960 as a reporter in Bristol, made Panorama presenter in 1974. Helmed his first general election night in 1979. Question Time chair since 1994.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments