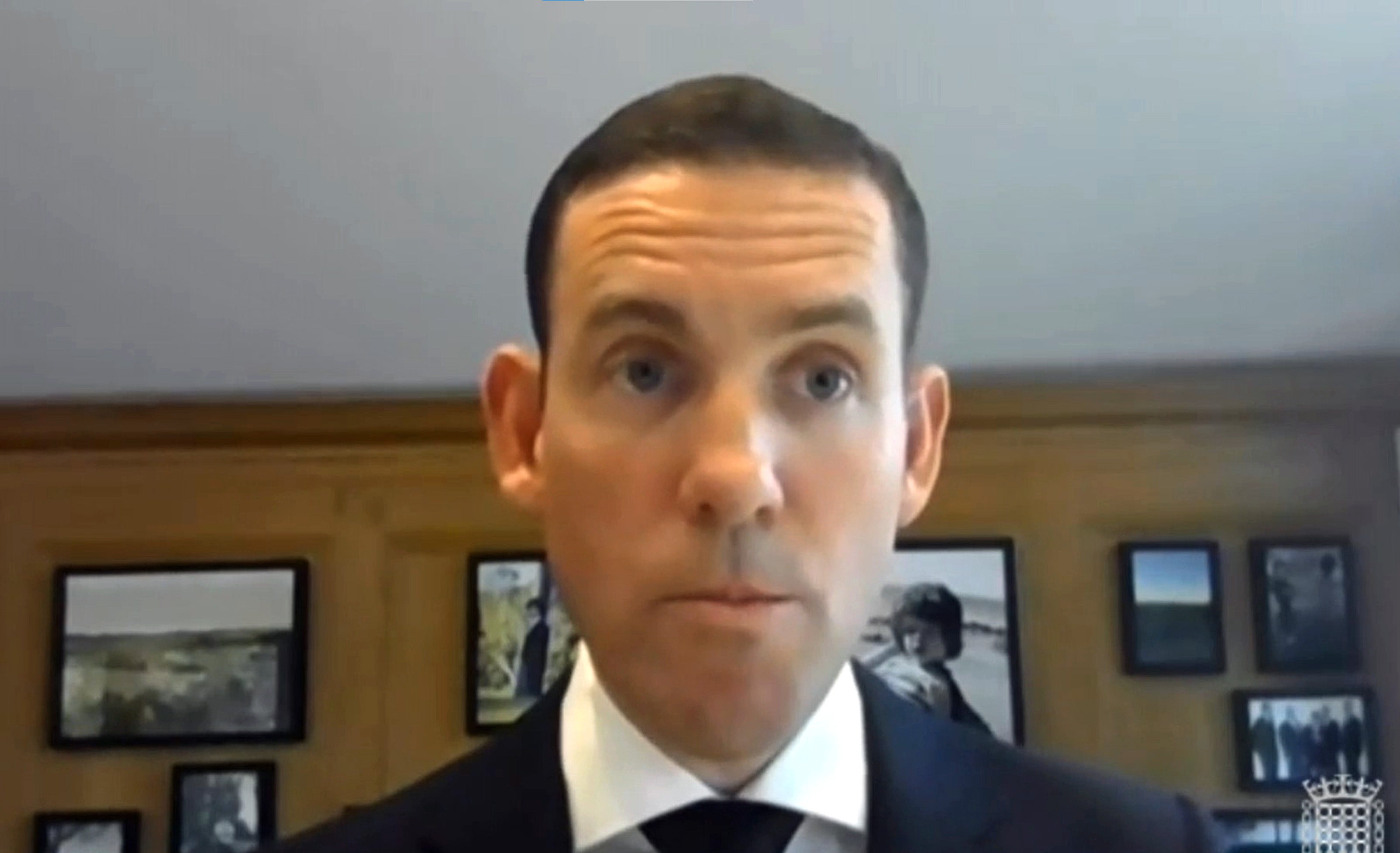

David Cameron: What is the Greensill lobbying scandal?

Former PM has insisted lobbying controversy is ‘all dealt with and in the past’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Cameron has made a shock return to frontline politics as foreign secretary, seven years after losing the Brexit referendum and immediately stepping down as prime minister.

Having also resigned as a Tory MP in September 2016, the former PM was handed a hastily-awarded life peerage on Monday, which entitles him to take up the role in Rishi Sunak’s Cabinet.

Following seven years out of the spotlight, Monday’s dramatic reshuffle generated more newspaper headlines and column inches involving Mr Cameron than any point since the Greensill lobbying scandal first broke in 2021.

Pressed about his role in the controversy on Monday, Mr Cameron insisted it was “all dealt with and in the past”, after seeking to duck questions by highlighting his other roles since leaving No 10 – including as president of the Alzheimer’s Research UK charity and teaching at New York University Abu Dhabi.

Concerns over Mr Cameron’s relationship with the supply chain finance firm Greensill Capital were first raised in March 2021, when the company went bust.

A host of subsequent Whitehall inquiries would go on to probe Mr Cameron’s work for the company – where he had held an advisory role since 2018 – and his relationship with the firm’s founder Lex Greensill while still in government.

While the ex-PM was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing in each of the lobbying inquiries, MPs on the Treasury committee noted that Mr Cameron had displayed “a significant lack of judgement” and said there was “a good case for strengthening” existing lobbying rules.

It emerged that Mr Cameron had embarked on an intense lobbying drive for funds during the Covid crisis, with revelations of increasingly desperate messages sent to chancellor Rishi Sunak, Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove and health secretary Matt Hancock, among other top government officials.

He had claimed it was “nuts” and “bonkers” for Greensill to be denied access to the Covid Corporate Financing Facility, a government-backed Covid loan scheme.

Mr Cameron and his staff sent ministers and officials around 73 emails, texts and WhatsApp messages relating to the now-collapsed firm in less than four months. He was unsuccessful in his approaches, but the bank was ultimately given access to another Covid-19 loan facility.

While the company’s collapse left investors and UK taxpayers facing huge losses, a BBC Panorama report in August 2021 suggested that Mr Cameron had made some £7.2m from Greensill Capital prior to it folding.

Questions were also raised about Mr Greensill’s links to Mr Cameron’s administration, after Labour unearthed apparent photos of an old business card describing the businessman as a “senior adviser” to Mr Cameron while he was prime minister.

A subsequent Cabinet Office inquiry led by lawyer Nigel Boardman found that Mr Greensill enjoyed “a privileged – and sometimes extraordinarily privileged – relationship with government”, and had a desk and security pass within the Cabinet Office, despite being neither a civil servant nor a special adviser.

That inquiry cited a memo to Mr Cameron in 2012 which made clear that cabinet secretary Lord Jeremy Heywood – who had worked with Mr Greensill during a sabbatical at Morgan Stanley – was “ the person primarily responsible for Mr Greensill being given a role in government”.

It was clear that Lord Heywood – who died in 2018 – “respected Mr Greensill’s capabilities” and had a “high regard for his integrity”, and that his appointment for an initial three-month stint as unpaid adviser was “properly made”, the Cabinet Office inquiry in 2021 found.

But a later extension which kept him inside government “raises significantly more questions”, found the 2021 Cabinet Office report, which also questioned whether there was any need for Greensill to have been provided with a government post, which he was able to leverage to gain clients for his private company.

Brushing off questions about the controversy on Monday, Mr Cameron told broadcasters: “All those things were dealt with by the Treasury select committee, and other inquiries at the time”.

He added: “As far as I am concerned, that is all dealt with and in the past. I now have one job, as Britain’s foreign secretary.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments