Outdated government messaging undermined Covid response, says former No 10 comms chief

‘New slide please’: Chris Whitty’s famous graphs made it onto screens with moments to spare

Outdated communications skills at the heart of government were exposed by the Covid pandemic to the extent that slides displayed at Downing Street press conferences were often completed minutes before being broadcast on live TV, Boris Johnson’s former media chief has revealed.

Lee Cain said failings in the government’s communications strategy “resulted in the public receiving mixed messages at a critical time”.

And he added that a hub of communications staff set up in the Cabinet Office to oversee official information campaigns the country plunged into lockdown was a “failure” because of inexperienced staff, unclear lines of responsibility, inconsistent policy and endemic leaks.

In a report for the Institute for Government (IFG), the former Downing Street director of communications – brought into No 10 by Boris Johnson after working with him on the Vote Leave campaign – called for the centralisation of official comms operation, a cull of hundreds of Whitehall communications officers and a shift towards TV, video clips and social media.

Cain also called for the revival of proposals for regular televised press conferences from the new TV studio in 9 Downing Street, ditched by Mr Johnson shortly after the comms chief and his ally Dominic Cummings quit last November.

He said the prime minister himself should host the briefings, rather than the then-Downing Street press secretary Allegra Stratton, whose recruitment to be the TV face of the government was behind Mr Cain’s departure last year.

But his analysis was challenged by IFG programme director Alex Thomas, who said that structural changes to government communications teams “won’t repair the damage that a lack of honesty and transparency from leaders has done to public trust”.

Successive governments have fallen “a long way from the gold standard of integrity and transparency needed to underpin trust”, and the Johnson administration of which Mr Cain formed part was “particularly guilty”, said Mr Thomas.

He pointed to examples of misleading government messaging including claims that the prime minister’s Brexit deal would not result in a customs border in the Irish Sea and a £100m advertising campaign devoted to the “fiction” that the UK would leave the EU on 31 October 2019 despite parliament having passed a law to prevent it.

“Confidence in government messaging depends on being able to distinguish political spin from factual information,” said Mr Thomas.

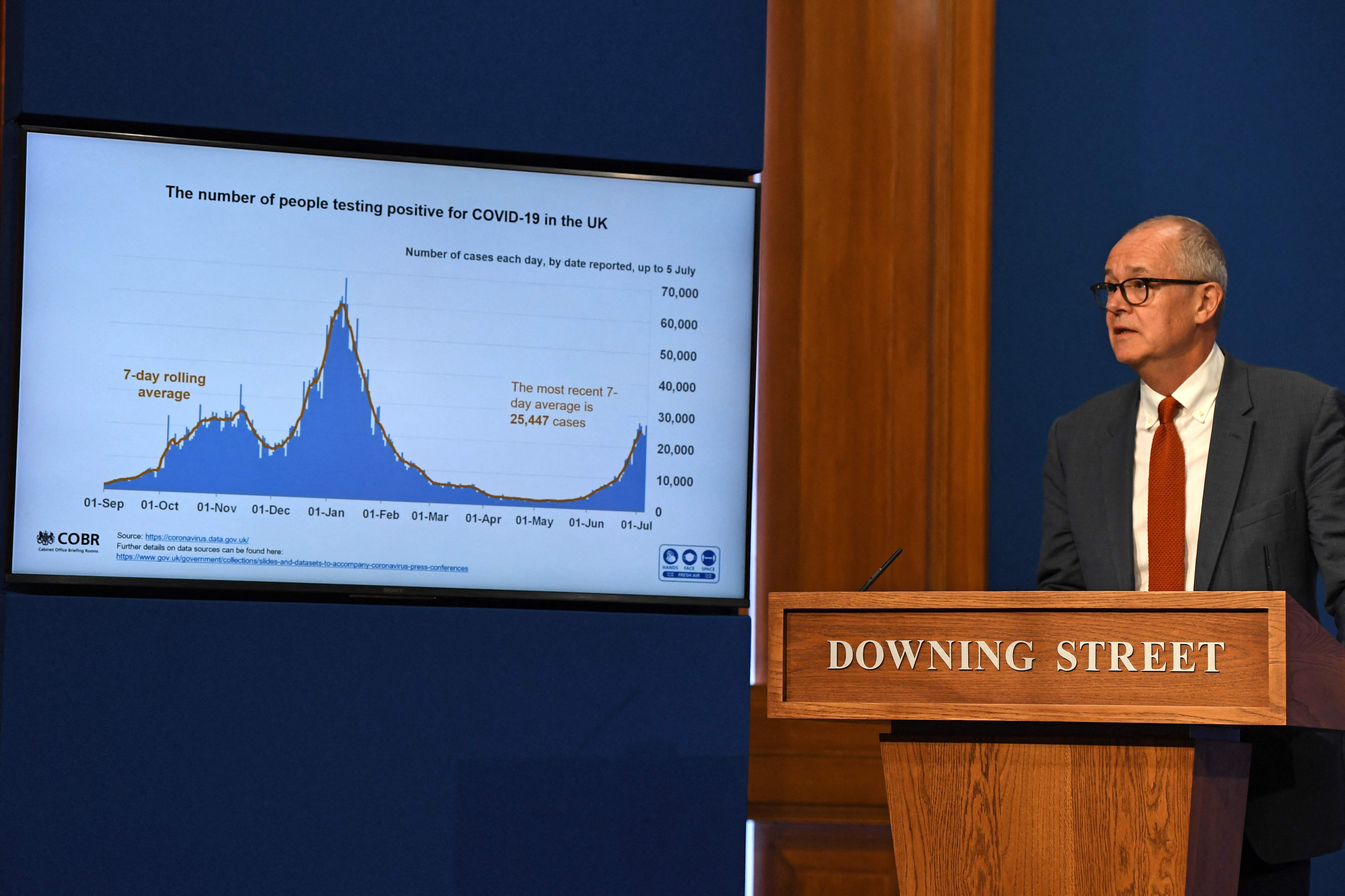

The phrase “next slide please” intoned by Chris Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance became a national catchphrase, immortalised on mugs and in internet memes, but Mr Cain’s report revealed that the graphs the government’s scientific advisers relied on to get their message across to the public were often delivered only by the skin of the communication team’s teeth.

“The centre had no data-visualisation capability in the early days of the pandemic,” said Mr Cain.

“Put starkly, there was nobody with the ability to create slides for the daily press conference – and even when a system was designed, people struggled with the skills required, and slides were often sent only moments before press conferences were due to begin.

While he said the failures were not the fault of individual communications officers, he pointed to a culture that “allowed basic modern news skills to become an afterthought” which uncovered shortcomings of the government's media operations at a time when the delivery of accurate and trustworthy information was vital.

“The first Covid campaigns were poor, the ‘hub’ system – a team of comms professionals based in the Cabinet Office to assist in the crisis – was a failure due to inexperienced staff and unclear lines of responsibility, policy development was inconsistent and leaking endemic.

The creation of the Cabinet Office hub was a standard Whitehall procedure in emergencies, but was exposed as a “layer of unnecessary bureaucracy” which largely duplicated the work of No 10’s own press office, he said.

A UK government spokesperson said: “These claims are misleading - throughout the pandemic we have set out clear, targeted and effective communications to help the public protect themselves, directly preventing millions of infections and saving thousands of lives.

“The Covid hub is delivering the biggest public information campaign since the Second World War, reaching an estimated 95 per cent of adults on average 17 times per week at the peak, using every means possible including social media, influencers, radio, TV and widespread digital marketing.

“GCS (Goverment Communication Service) is internationally recognised as a world leader in public communications, demonstrated by our work across the globe in over 25 countries.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks