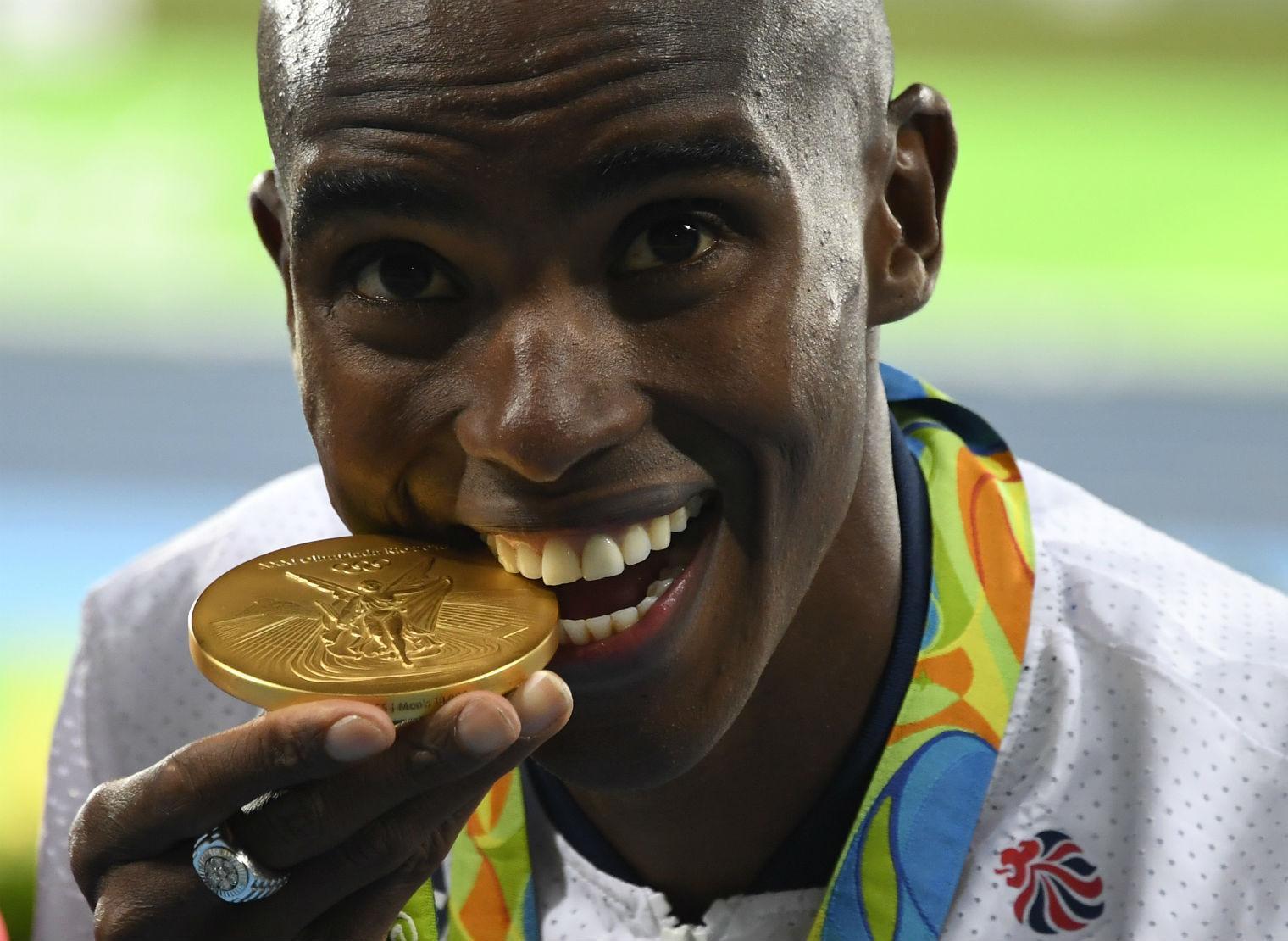

Rio 2016: Could this be Team GB’s last great Olympics after Brexit?

Exclusive: Former Olympics Minister among those to warn decision to leave EU could starve elite sport of funds to train British athletes

Rio 2016 could be Team GB’s last truly great Olympic Games, as concerns mount that forthcoming political and economic upheaval as a consequence of the UK’s decision to leave the European Union will make it difficult to sustain the investment in sport necessary for British athletes to deliver the dominant performances the country has come to expect from them at Tokyo 2020 and beyond.

The former Chancellor George Osborne pledged a 29 per cent increase in exchequer funding for elite sport in what turned out to be his final Autumn Statement last November. That spending commitment is yet to be confirmed by new Chancellor Philip Hammond, while other commitments on maintaining funding levels for EU backed subsidies and investments have been. Mr Osborne's commitment remains in place but Mr Hammond is expected to 'reset' economic policy in his first autumn statement later this year.

Privately, UK Sport, the body that chooses where to spend the roughly £450m per four-year cycle that is available for elite sport, are fearful of the consequences of a general economic downturn or even recession even before the next games.

According to Labour’s former Olympics Minister Dame Tessa Jowell: “If, in 2020, we’re looking back at a team GB that has not performed at the level that it did Rio or in London then it will be fair to say that Brexit was one of the reasons.

While spending on elite sport has been maintained in the wake of the UK’s hugely successful home Olympics four years ago, with the consequences clear to see in Rio 2016, local facilities have faced severe cuts ever since 2008, a course of action that eventually, inevitably affects the top end.

In recent years, all Olympic hosts have invested heavily in elite performance in advance of their own home games and seen their medal haul begin to taper off one to two contests later.

“What Team GB’s triumph has shown is that investment creates results,” Ms Jowell said. “Every gold medal is a return on about £5m of investment. If we are going to go on building our domination as a nation in a way that would have been unthinkable ten years ago then we’ve got to go on investing in our athletes. The challenges of high performance intensify all the time. We've got to be able to fund that progress.”

During the previous recession, cutting funding to elite sport was not considered an option, with London 2012 looming on the horizon. But cuts to local facilities were made, including the increased sale of school sports pitches under the former Education minister Michael Gove. The consequences of these decisions for elite sport were not felt in time for London 2012, but the concern is that they will be.

“We’ve been focussing on investments in elite athletes but you've got to keep growing the pipeline and you do that by promoting every possible opportunity for talent and talent development,” Ms Jowell added. “That’s why investment in sport can’t be limited to investment in elite sport alone. It has to be investment in local facilities and in school competition.”

In December, the Sports Minister Tracey Crouch launched a new strategy, called Sporting Future, designed to better align grassroots sport with elite sport, so that a talent pathway is clear all the way from school or a local club, right through to elite national training programmes. But keeping the pipeline wide enough at its entry point is the most difficult and the most costly part.

The exact breakdown in elite sport funding from the exchequer and from the National Lottery is complex, but around two thirds of funding, or £300m over four years, comes directly from National Lottery funds. Since Camelot introduced more balls to the standard draw last year, making it three times harder to win the jackpot, and with no one now winning the jackpot on three quarters of the bi-weekly draws, many regular players have taken to playing foreign lotteries instead using specialist websites. Last month, Camelot raised the price of a ticket to £2.50. Camelot maintains that it is enjoying record ticket sales, but Mr Osborne’s raising of the payment level direct from government is understood to have been necessary to cover a temporary shortfall in lottery revenues. If the national lottery’s popularity suffers a slump, the consequences will either be disastrous for sport, or costly to the taxpayer.

It is 11 years since London won the right to host the Olympics, with a very clever marketing strategy that promised to use the games to capture the attention of talented children watching on television, and turn them into the Olympic champions of the future. This Olympic legacy, as it will always be known, was having mixed success, but it has never been at graver risk than now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks