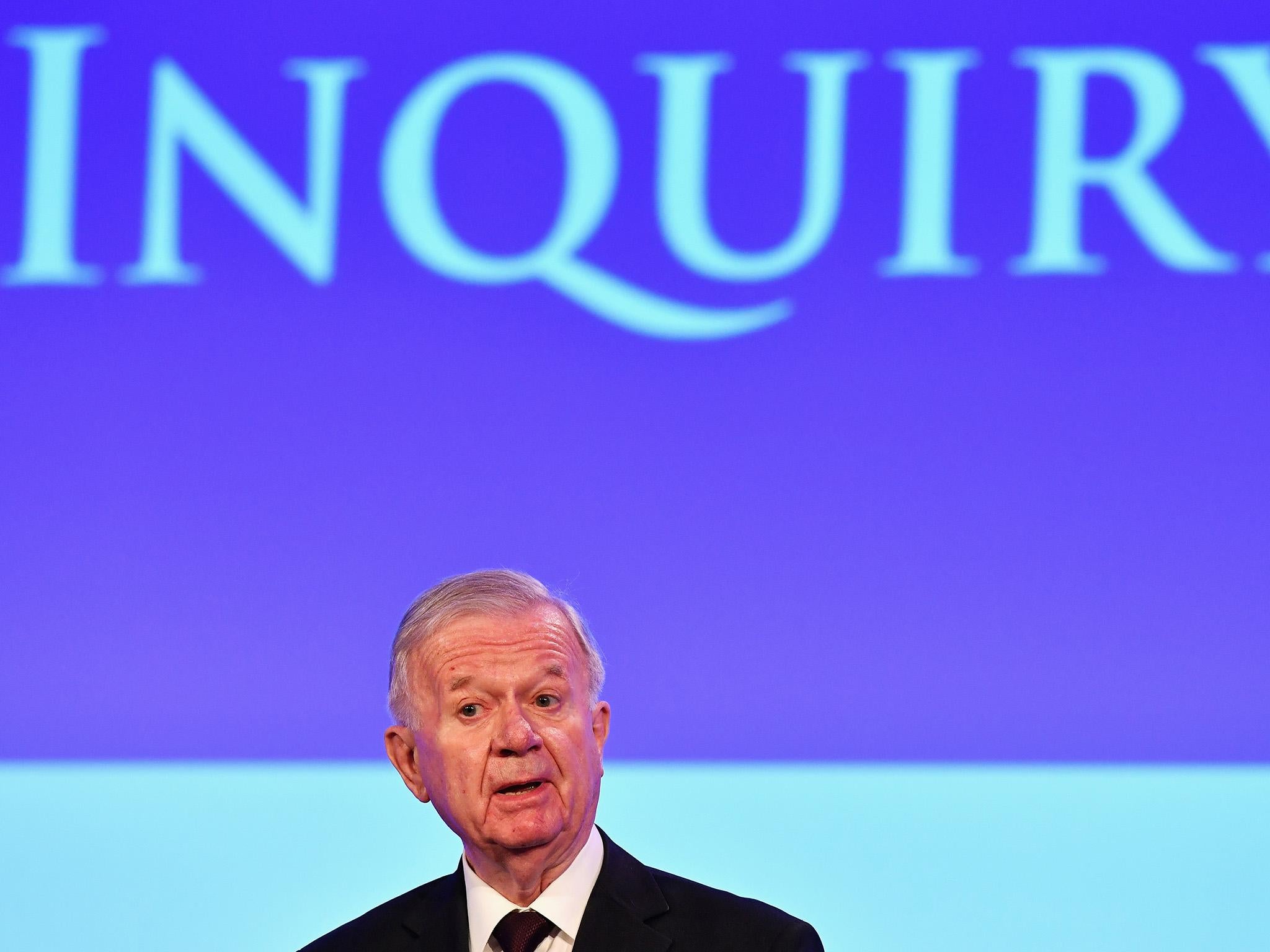

Chilcot report: The curious case of the seven-year inquiry and the big questions left unanswered about the Iraq War

The Chilcot report was immensely long and full of detail. Its conclusions were much clearer than many people expected they would be. And yet, despite the thousands of man hours and millions of words that went into the 12-volume report, there are some significant questions which, frustratingly, still need answering

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.1. Was the invasion legal?

Not only does Sir John not offer a judgement on whether the law was legal – nor does he answer the intriguing question of why the attorney general, Lord Goldsmith, altered his legal advice just before the tanks rolled across Iraq’s borders. It notes that twice, in January 2003, Lord Goldsmith gave Tony Blair advice on the legal issues, which no one else in the Cabinet saw. On 7 March, 12 days before the outbreak of war, Lord Goldsmith delivered his view that the “safest legal course” would be for the US and UK to persuade the UN Security Council to pass a new resolution authorising military action. By 13 March – when it was apparent that there was not going to be a new UN resolution – he arrived at the “better view” that the invasion would be legal none the less.

Why? Sir John Chilcot does not appear to know. His conclusion is that Lord Goldsmith should have been made to supply a written explanation, but no one in the Cabinet at the time called for it.

2. What was the truth about the French veto?

Tony Blair and Jack Straw have consistently blamed the French President, Jacques Chirac for the fact that they never asked the UN Security Council for a second resolution authorising the invasion. On 10 March 2003, Chirac gave a television interview in which he said that UN policy was to disarm Iraq peacefully through weapons inspections, but that some UN members – he meant the US and UK – were now saying that "in so many days we go to war". Therefore France would say no to a second resolution "whatever the circumstances".

Did those words, "quelles que soient les circonstances", actually mean that the French were never going to countenance military action? Or were they ripped out of context to give the UK an excuse for not going back to the UN to seek support for the war? Critics of Blair have insisted that his words were twisted, and that Chirac had clearly stated immediately beforehand that, if weapons inspections were allowed to run their course, circumstances might ultimately arise in which “regrettably, the war would become inevitable” – in other words, France would support a second resolution.

Some, including Clare Short, have suggested that this subtle misrepresentation was deliberate, while Stephen Wall, Blair’s former EU adviser, gave evidence to that effect to the Chilcot inquiry. Wall added that Blair gave “Alastair [Campbell] his marching orders to play the anti-French card".

Does Chilcot agree? Was Chirac smeared? Sir John’s report does not say.

3. Should Blair have known there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq?

The former Prime Minister is rebuked in Sir John Chilcot's report for the foreword he provided to a dossier presented to Parliament in September 2002, which referred to Iraq’s possession of WMDs as if that were a known fact. The intelligence reports were not so emphatic, Sir John said, but he accepts that Tony Blair firmly believed that those WMDs existed.

Those who claim that Blair knowingly lied about WMDs point to an interview that Saddam Hussein’s son-in-law, Hussein Kemal, gave to CNN after he defected to Jordan in 1995. Kemal said: “Iraq does not possess any weapons of mass destruction. I am being completely honest about this.” He was in a position to know because he had been in charge of Iraq’s weapons programme. We now know that he was telling the truth. Why wasn’t he believed? More specifically, was Blair aware of that part of Kemal’s intelligence when referred to it in the Commons on 10 March 2003 and assured MPs that it was “contrary to all intelligence” that Saddam had “decided unilaterally to destroy the weapons”? If so, was he not misleading Parliament? And, if not, would it not be helpful to clarify the matter?

Unfortunately, Chilcot appears to have nothing to say on this question.

4. Did Blair mislead us about preparations for war?

For public consumption, Tony Blair maintained almost until the day the invasion began that Saddam Hussein could avoid war by complying with UN Security Council resolutions. This would seem disingenuous. Hard liners in the Bush administration such as Vice President Dick Cheney and the Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld were not interested in UN resolutions or WMDs – they wanted to send in the troops to overthrow Saddam regardless.

Given that there was a clear difference between the aims of the US and UK governments, why did Tony Blair send that private note to George Bush in July 2002 saying “I will be with you, whatever” – around the same time that he told journalists that “no decision has been taken” to go to war. Blair now claims that the note was not a commitment to join the US in going to war. In that case, what did it mean? Was there ever any possibility that the US could have gone to war without the British? And, crucially, what does Sir John Chilcot think about such fundamental questions?

His report does not say.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments