British government's shambolic response to Chernobyl disaster detailed in newly released documents

'The ill-co-ordinated nature of the information and advice aroused rather than calmed public anxiety'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Radioactive fallout from the Chernobyl disaster started arriving in the UK during a bank holiday weekend, plunging Whitehall into chaos, newly released official files show.

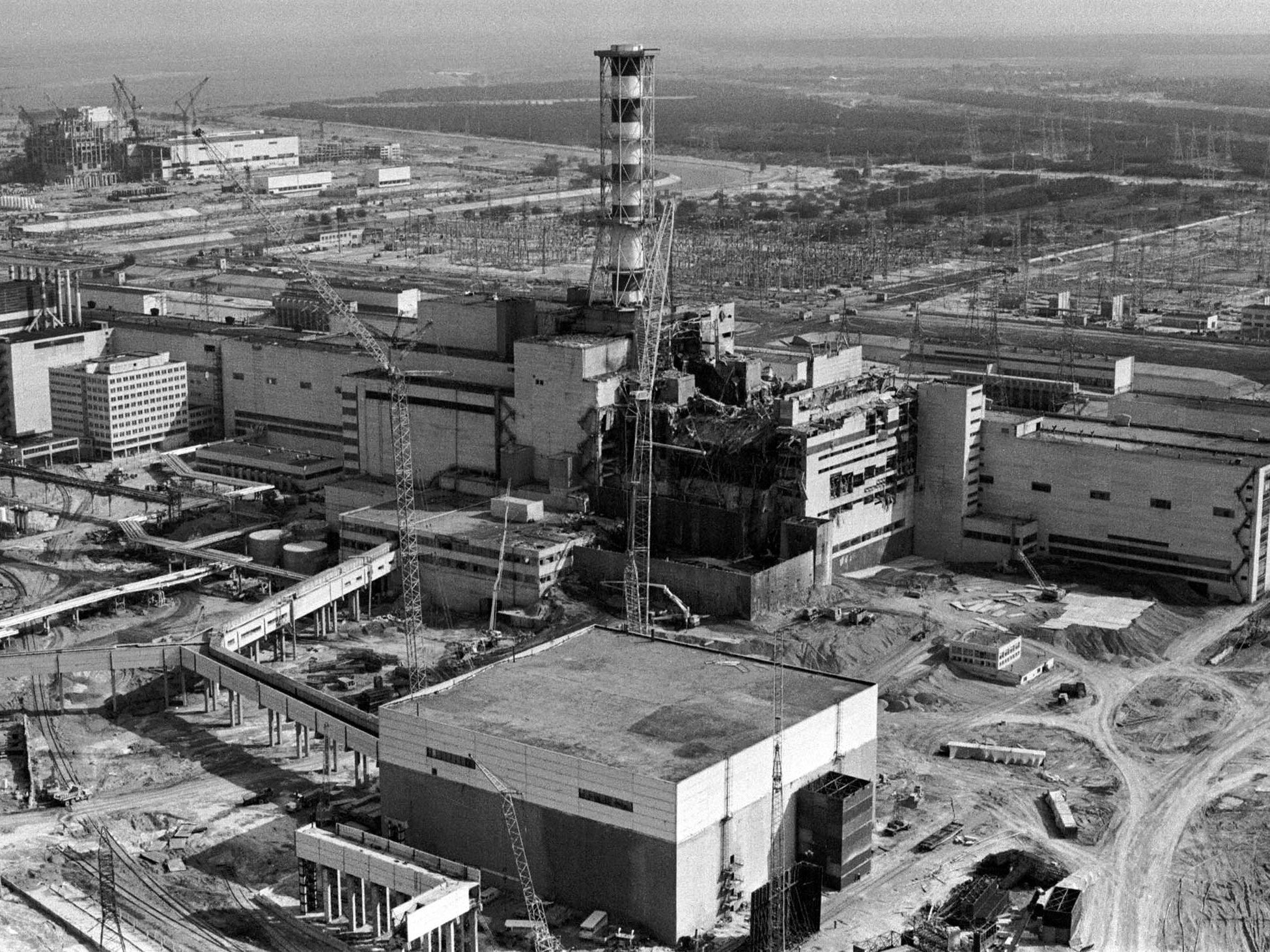

The catastrophic explosion at the Soviet nuclear reactor on 26 April 1986, the world's worst nuclear accident, released radioactive plumes high into the atmosphere.

It was another week before the first signs of increased radioactivity levels were detected in the UK, just as officials were packing up for the long May bank holiday weekend.

With Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister, out of the country on an official visit to Japan, government files released by the National Archives at Kew suggest the immediate response was shambolic.

Phone lines were overwhelmed and advice issued to calm public fears only inflamed them.

Officials were dismayed to discover they did not have a contingency plan for dealing with an incident involving an overseas nuclear facility.

In one moment of pure "farce", William Waldegrave, the Environment Minister, mistakenly gave out the telephone number for the Department of the Environment (DoE) drivers' pool instead of Whitehall's technical information centre during a radio interview.

Ms Thatcher complained the government had given the "appearance of disarray" in her absence, while a scathing post-mortem by the No 10 policy unit concluded Whitehall finally gained control only after the bank holiday.

In his report to the prime minister, John Wybrew, of the policy unit, wrote: "Over the bank holiday weekend, when the fall-out first occurred, you, [Foreign Secretary] Geoffrey Howe and (No 10 Press Secretary) Bernard Ingham were away in Tokyo. Whitehall lacked a firm lead.

"Anxious telephone callers inundated Maff [the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries] and seriously hampered communications. Not until after the weekend did DoE and environment ministers firmly take charge of the government's response.

"Before that, the ill-co-ordinated nature of the information and advice aroused rather than calmed public anxiety."

The Environment Secretary, Kenneth Baker, sought to assure the public the risks were "insignificant," only for John Dunster, the head of the National Radiological Protection Board, to say the death toll in the UK would run to "tens of people".

"Both conclusions derived from the the same assumption and analysis. Mr Dunster was quantifying what he regarded as an insignificant risk," Mr Wybrew noted.

"The next day he had to explain that tens of deaths would arise from cancer over the next 30 to 40 years, during which time millions would die from cancer wholly unconnected with the Chernobyl incident."

Additional reporting by Press Association

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments