Caroline Lucas reveals 10 things no one tells you before you first enter Parliament

Lucas is the Green MP for Brighton Pavilion, who became the Party's first MP in 201

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Entering Parliament for the first time is a daunting experience. MPs for parties already represented at Westminster have their parliamentary colleagues to turn to for advice and support. As the first MP for my Party, the Greens, it was a question of learning through experience...

1. Election night is not all that it seems

Election night is one of the few national rituals familiar to us all. First the pundits in the studio, the exit polls and computer graphics, marginal seats and swingometers. Then the results themselves: brief scenes of candidates shuffling on to a platform in a draughty hall, their set faces and rosettes somehow placing them apart from the rest of the human race. But it turns out that when you see all the candidates looking slightly sick, as they wait for the returning officer to read out the results of the election, they actually already know the outcome. They've been told about five minutes earlier.

2. You've got to fight for your right, to have an office

Allocation of offices is by the party whips because, as with so much else in Westminster, rooms are a currency or a perk. The better rooms go to the more senior MPs, or as rewards to those who follow the party line. If you are prepared to serve on the less exciting committees, and vote loyally with your party leader, then come the next election, you may be rewarded with a room closer to the tea room or further way from the toilets. Those at the top of the tree end up with a view of the River Thames. If you rebel, or belong to one of the smaller parties, you can go to the back of the queue and wait for your chance to squeeze into a broom cupboard with limited ventilation.

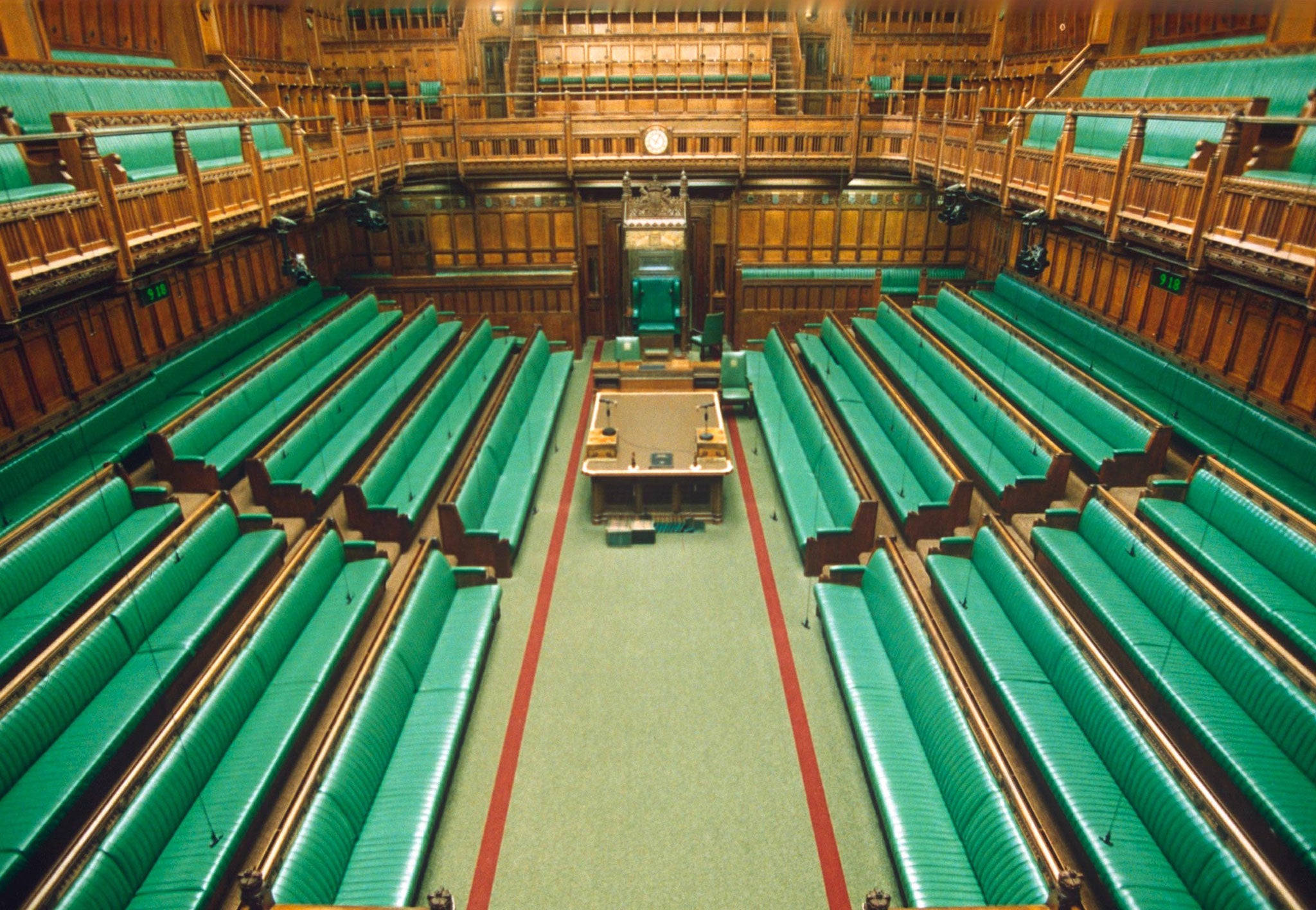

3. Parliament is like Hogwarts meets Gilbert and Sullivan

Portcullis House, the modern office building where most MPs hope to have their offices, is connected to the main Palace of Westminster by an underground tunnel. Compared with the modern, glassy, coffee-lounge atrium of Portcullis House, the old Palace seems rather drab. The wood panelling is gloomy, the carpets have come straight from a 1970s pub, and there's a pervading smell of school dinners. But the chamber itself is still impressive, albeit surprisingly small. In fact, it can only accommodate about two-thirds of the current 650 MPs. To make sure of being able to 'bag a place' at the big set-piece debates like the budget statement, Members have to fill in 'prayer cards' to reserve their seat.

4. There's no smoking – except for snuff

A curious survival of the 18th century is the provision of snuff, at public expense, for Honourable Members and Officers of the House, at the doorkeepers' box at the entrance to the Chamber. Admittedly, I've never actually seen any MP having a quick snort before going in – although I did try a bit myself, just to test it. Snuff is apparently the only form of tobacco to be tolerated in or around the Chamber: smoking has been banned there and in committees since 1693.

5. There are no 'Honourable Friends'

A strange convention of Parliament is that you do not call other MPs by their names when speaking in the chamber. You don't say, "Eric Pickles is talking rubbish," for example. Instead you say, "The Honourable Member for Brentwood and Ongar is talking rubbish". Some MPs are accorded a higher status: so when Eric Pickles joined the Cabinet, he also became a member of the Privy Council (don't ask) and so he is entitled to be called "Right Honourable". And if the MP you are talking about is from your own party, then you say "My Honourable Friend".

6. The division bell rush is madness

When a vote is called – which can happen at any time – a 'division bell' begins to clang throughout the Palace (and in various bars and restaurants in the surrounding streets) to warn MPs that they have eight minutes to reach the voting lobbies. You have to drop everything and run for it. MPs then crowd into the lobbies and file through one of two doors – the 'Ayes' who support the motion, and the 'Noes' who don't – where they are counted and their names recorded. The whole pantomime takes at least 15 minutes for each vote, which means there's only enough time for MPs to vote on a tiny proportion of the amendments put forward for each bill. It's excruciatingly inefficient.

7. Most MPs have no idea what they're voting on

One of the most shocking things to me was the discovery that most MPs have no idea what they're voting on, when the division bell rings. And it suits the whips to keep it that way. The fact that my modest proposal – that Members should be required to include brief explanatory statements alongside their amendments – was met with such hostility by the Party hierarchies is indicative of the threat posed to Party discipline by MPs actually thinking for themselves. Sometimes MPs go through the wrong voting lobby by mistake – and rather than having to explain their error to irate whips, have been known to hide in the toilets inside the lobby until the voting is finished.

8. You can't breastfeed – or wear T-shirts with slogans

The parliamentary rules on dress code have always seemed a bit of a mystery to me, but they appear to exercise a number of colleagues. For example, Labour's Thomas Docherty seems to have a problem with women wearing denim in the House, even asking for guidance "as to what is an appropriate dress code for the mother of Parliaments". I soon discovered that wearing a T-shirt with the slogan 'No More Page 3' was definitely inappropriate. The irony of being told to "cover up" while debating newspapers selling images of topless models was priceless. But there's an important distinction to be made between the customs of Parliament that are comic-but-irrelevant, like Black Rod's silk stockings, and those which are decidedly comic-but-harmful, like the ban on breastfeeding – a terrible signal to send to women thinking of standing for Parliament.

9. Whips are all-powerful

Another shock was to see how the powers of parliamentary scrutiny are so poorly exercised. Membership of the ad hoc 'bill committees' set up to go through draft legislation line by line is one of the best opportunities to have direct influence over future laws. That's why the whips generally try to keep people with too much expertise or independence of mind off these committees. Sarah Wollaston, the Conservative MP for Totnes and a former GP, tells of her enthusiasm to sit on the Health and Social Care bill committee. Instead, the whips told her to sit on a committee examining double taxation in the Cayman Islands. When she protested that she knew nothing of the subject, the whips replied that was all to the good: all they wanted her to do was to vote the right way at the right time.

10. Emily Wilding Davison's legacy lives on

In the corner of Westminster Hall, behind some discreet black railings, lies a staircase leading down to the very beautiful Chapel of St Mary Undercroft. For the past 700 years, it has been the main place of Christian worship in the Palace of Westminster, aside from brief periods as a wine cellar and a stable for Oliver Cromwell's horses. On census night in 1911, suffragette Emily Wilding Davison hid in the broom cupboard next door to the Chapel, so she could legitimately give her place of residence as the House of Commons. This little bit of history has been lovingly preserved by Tony Benn, who put up a commemorative plaque on the back of the broom cupboard door – quite illegally, as he later recounted with pleasure.

'Honourable Friends? Parliament and the Fight for Change' by Caroline Lucas (£14.99, Portobello Books) is out now

A view from a disenfranchised youth

When this magazine's editor wrote a TV review about politics, Ella Marshall wrote a letter to protest its tone: "Next time you want to publish an article with consideration towards young people, I suggest you let one of us write it". So we did. Here's what Ella, 16 – and a Youth MP– had to say on behalf of those too young to vote

* Give us our vote. Lower the voting age to 16 and re-engage young people with the governance of our country. Sixteen is the age at which we may pay tax, are able to have sex and sign up to the military and yet we're not mature enough for the basic human right to contribute to democracy? Don't be afraid of amplifying our youthful, and possibly more alternative, political opinions.

* Education shouldn't be used as a political football. If you do reform schools further, it must be a method by which you can help us grow into rounded human beings, rather than a labour force worn down by our own target grades before the age of 16. We need a curriculum for life. This means professionals visiting schools who are able to teach us about both the physical and emotional aspects of sex. And please stop putting merciless amounts of pressure on our hard-working and dedicated teachers.

* Hands off the NHS. Government officials who are rich enough to afford private healthcare have been progressively selling off sections of our most essential public service for the past five years. There is no way that moving towards a more privatised system will benefit anybody, other than the privatisers.

* We want less "long-term economic plan" and more "ordinary lives matter". Every 11 minutes, a family in Britain find themselves homeless and yet, according to the Office for National Statistics, there are over a million empty homes in England and Wales. The richest 1 per cent of people have the same wealth as 55 per cent of the population. We, as young people, are taught about the importance of paying tax and contributing to society and yet there seems to be a different standard for the financial elite.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments