Budget 2013: So, how do you budget your way out of a recession?

Andy McSmith on other austerity chancellors' attempts to restore growth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

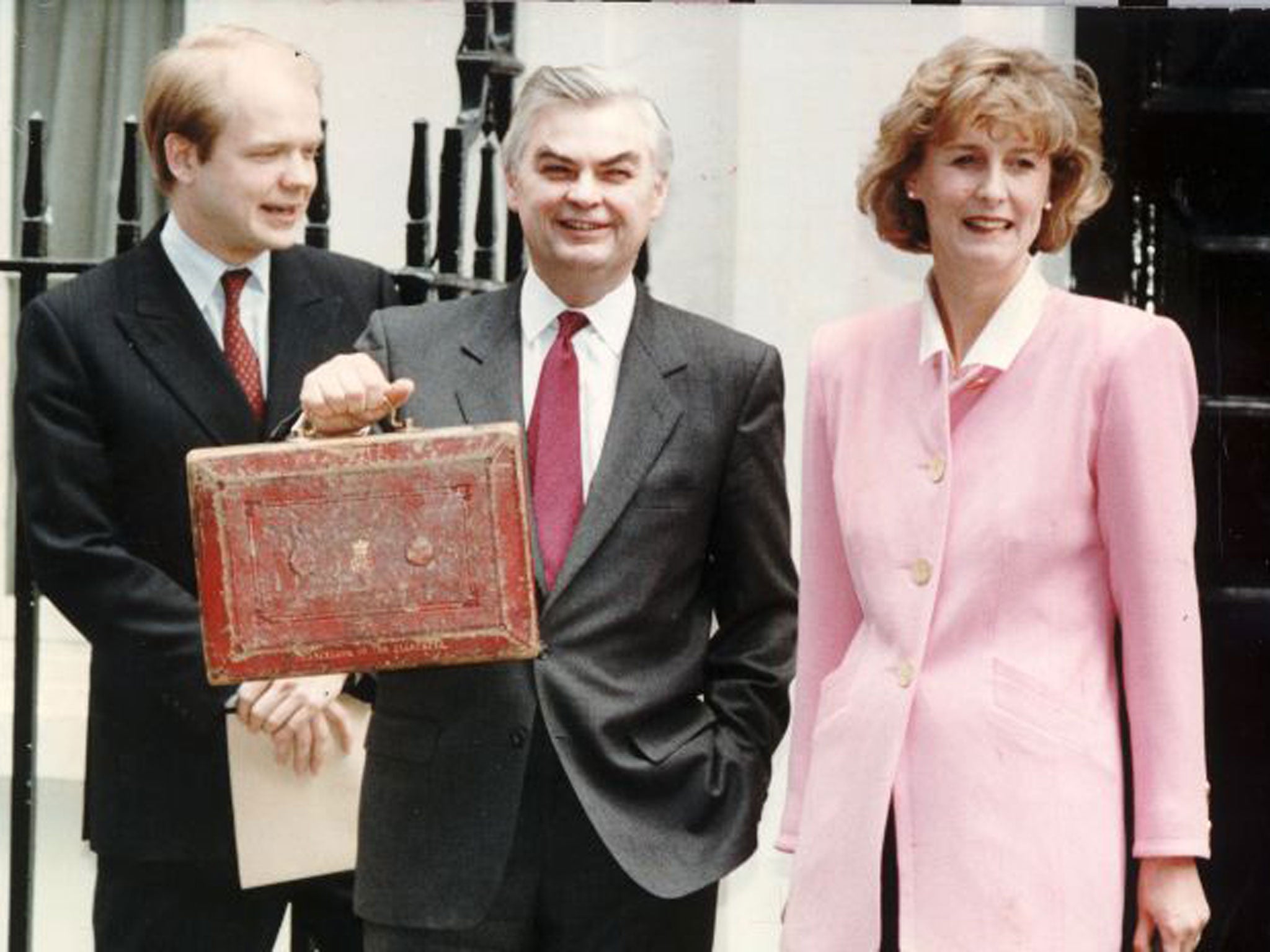

Your support makes all the difference.Norman Lamont 1991

Delivered his debut budget at a time of crisis. The economy was gripped by the dual problems of recession and rising inflation, but extraordinarily, that was not the main problem on the Chancellor's mind. Margaret Thatcher had been removed from office only four months earlier, largely because of the unpopularity of the poll tax. For a decade the Tories had been reducing government grants to local councils, hoping that it would force them to reduce their spending. The poll tax was the culmination of that campaign. After Thatcher's fall, the Government legislated to replace the poll tax with a less controversial council tax, but there were still that year's poll tax bills threatening to destroy the Conservatives' chances of re-election. So Lamont shoved VAT up from 15 per cent to 17.5 per cent, and used the proceeds to cut £140 from every poll tax bill. In a couple of London boroughs – Westminster and Wandsworth – and a few scattered parishes, people found that their poll tax bills were down to zero. It was shrewd politics. People were so pleased with the one-off reduction that they did not complain about the permanent rise in VAT. The Conservatives won the following year's general election, only to be hit by the worst sterling crisis since the 1970s.

Geoffrey Howe 1981

After the cruel lessons of the 1930s, every Western government accepted the advice of the economist John Maynard Keynes that the Government should increase spending during a recession to stimulate growth. In the UK, unemployment had been rising steadily, and by January 1982, it would exceed three million for the first time since the 1930s, but Margaret Thatcher and her Chancellor, Geoffrey Howe stuck to their belief that sound money mattered more than growth. Inflation had gone above 21 per cent in May the previous year, and was still in double figures. Government spending was only just under half of GDP, Howe had planned to reduce the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement from £9.25bn, the figure he inherited from Labour, to £8.25bn instead of which it was projected to rise to £14.5bn. So instead of a stimulus to growth, Howe announced a grim package of tax increases. This caused such a shock that 364 economists, including the future Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, signed a letter to The Times warning that monetarism, the political philosophy behind the Budget, would not work. However, it worked for Thatcher. Though unemployment continued rising, inflation came down, which restored confidence in the Government.

Denis Healey 1976

The Labour Government was so unpopular in the mid-1970s, and so unpopular that every by-election in a Labour seat cut another slice off their tiny parliamentary majority. The biggest single cause of their woes was the hike in world oil prices imposed by the oil producing nations after the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. Inflation had peaked in 1975, but was still running at over 21 per cent in March 1976. This was causing a cycle in which prices went up, whereupon the well-organised trade unions demanded and got wage rises, which pushed prices up again. Average earnings rose by nearly 28 per cent during 1975. Healey therefore became the first Chancellor to give an outside body a veto over tax policies. He promised to reduce tax, by raising thresholds and increasing allowances, if the TUC would agree to a three per cent cap on pay increases. It did not work. The rate of increase of earnings slowed to around 14 per cent over the year, and inflation came down, but by the autumn, Healey had to go to the International Monetary Fund to make a humiliating request for the UK to be bailed out.

Anthony Barber 1972

In 1972, the UK was hit by mass unemployment for the first time since the 1930s. The news, in January 1972, that the jobless figure had risen above a million caused such mayhem in the House of Commons, with boos and catcalls directed at the Prime Minster, Edward Heath, that the sitting had to be suspended. The cause of the problem was a long term failure of British industry to get productivity up to the levels of competitors such as the US and Germany. Anthony Barber decided that the solution would be a "dash for growth". He cut income tax by £1bn, and introduced increased tax concessions for industry forecasting that the economy would grow as a result by 10 per cent in two years, professing not to be worried by the increase in government borrowing. Unfortunately, the country was soon facing rapidly rising inflation, and within 15 months, the Government had to make a dizzying U-turn, introducing deflationary measures and trying to impose a wage freeze, which led to the 1974 miners' strike which brought down the Government and prepared the way for the rise of Margaret Thatcher.

Philip Snowden 1931

The stock market crash of 1929 produced frightening levels of unemployment. In December 1930, the Ministry of Labour announced that there were 1,766,393 "wholly unemployed" and another 876,729 "temporarily unemployed" – a total of 2,643,127. A Labour government might have been expected to put job creation at the top of their agenda, and a number of influential politicians, including Lloyd George, Oswald Mosley, and John Keynes, were urging them to run up a deficit to create growth. But the Labour Chancellor, Philip Snowden, believed rigidly that a government should spend only what it could raise from tax, and was under pressure from the Bank of England not to protect the value of the pound. He also believed in free trade, when other Labour politicians wanted to raise tariffs to protect British manufacturing. In his Budget speech, which Keynes described as "replete with folly and injustice", Snowden announced tax rises, a cut in unemployment benefit, and cuts in public salaries. The result was a slump that forced the UK off the gold standard, riots, a split in the Labour Party, and the creation of a national government nominally led by the former Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, though actually controlled by the Conservatives.

Winston Churchill 1925

In 1925, the overall economic outlook was improving, except for one major problem. Britain was a trading nation, which needed to export, but British goods were too expensive. Coal exports were a particular problem, which the Chancellor, Winston Churchill, attributed solely to bad management in a privately-owned industry. The real problem was that sterling was priced too high in comparison with the dollar, or the price of gold. However, a Chancellor as patriotic and addicted to grand gestures as Churchill was not eager to devalue the pound. He claimed that when considering why coal exports were so low, the exchange rate was about as relevant as the Gulf Stream. Keynes dismissed that view as "feather-brained". Taking advice from others, about which he may have had private doubts, Churchill put sterling on the Gold Standard, so as to fix its rate against the dollar at $4.80 to the pound, permanently. Because the figure was so high, the problems for British exporters, particularly the mine owners, were exacerbated. The answer, the Government decided, was to tell coal miners to take a wage cut. That set off a miners' strike, which in turn led to the general strike.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments