David Cameron: His leadership highs and lows

From 'heir to Blair' to a calamitous fall from grace

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Cameron’s rise to the Conservative Party leadership was as swift as his unexpected fall from grace. In between, he had a rollercoaster ride.

Eleven years ago, the 38-year-old Cameron was very much the outsider when he entered the contest against the more experienced David Davis, Kenneth Clarke and Liam Fox after the Tories lost their third successive general election victory.

Few Tories gave the then shadow Education Secretary much chance but he wowed the party faithful at their annual conference in Blackpool and went on to defeat Davis in a ballot of the membership on a modernising ticket.

Cameron echoed the strategy of Tony Blair, whom he called “the master” and once described himself as “the heir to Blair.” He “hugged a husky” on a trip to the Arctic Circle in 2005 to highlight his commitment to tackling climate change. He told his party that it should embrace civil partnerships and, ironically, to “stop banging on about Europe.” He said GWB (General Well Being) mattered as well as GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and declared “Let sunshine win the day.”

But his leadership came under pressure as Gordon Brown considered a snap election in 2007 for which the Tories were unprepared. Cameron and his closest political ally George Osborne announced a popular pledge to raise the inheritance tax threshold to £1m and Brown bottled an election Labour almost certainly would have won.

Cameron’s nadir was the death of his disabled son Ivan at the age of six in 2009. He spoke movingly about sleeping on hospital floors. His family’s experience helped to reassure some voters with doubts about the Tories’ commitment to the NHS. He never hid his privileged background but argued: “It’s not where you come from, but where you take the country.”

His modernising crusade had its limits. After promising to match the Labour Government’s spending plans, he and Osborne reverted to Tory type by pledging to cut the deficit after the 2008 financial crisis. Their landmark decision set the tone for the Coalition Government formed by Cameron after the 2010 when he dislodged Brown but needed the support of the Liberal Democrats to secure a Commons majority. Cameron became the youngest prime minister since 1812 at the age of 43.

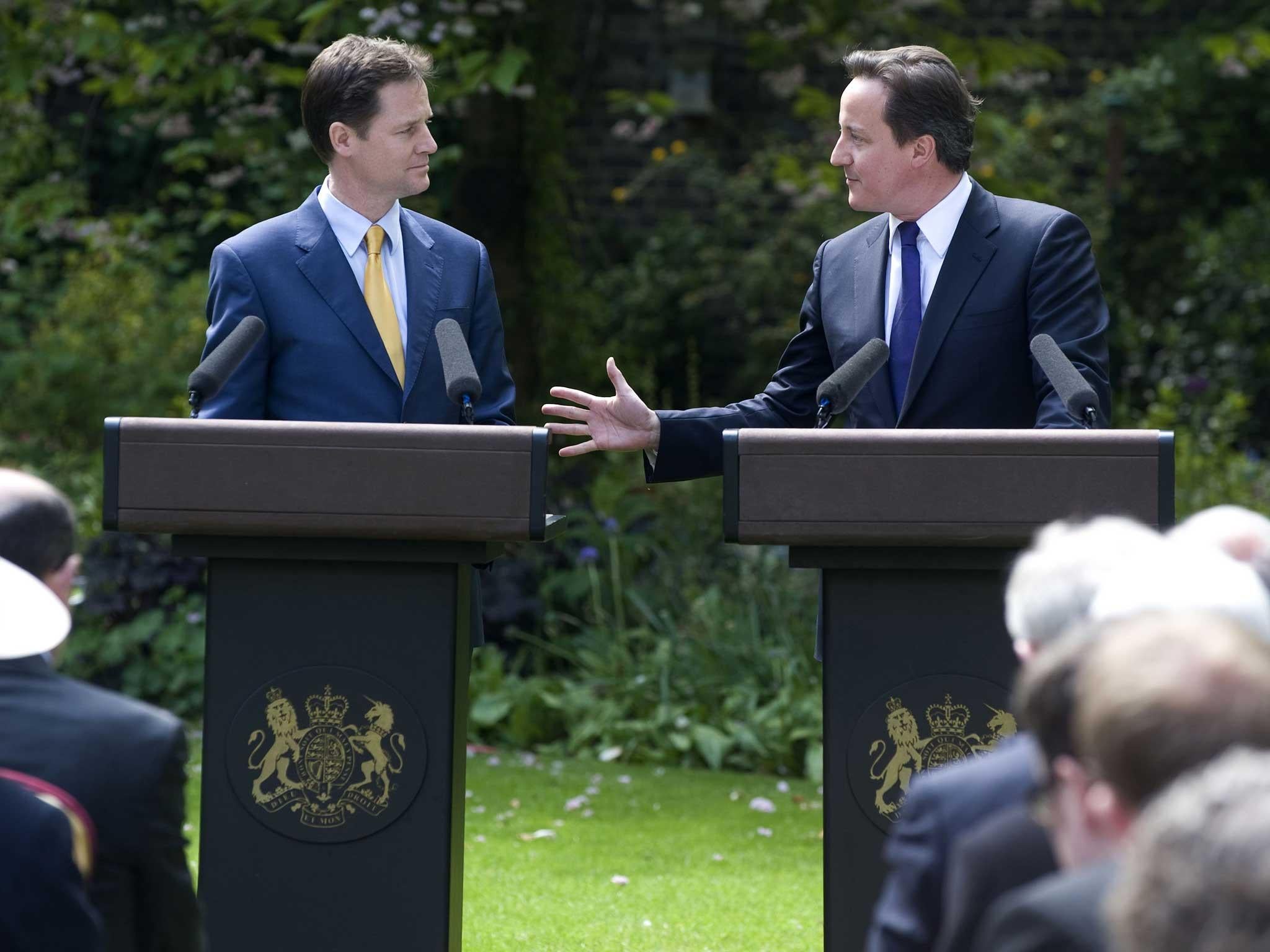

As a pragmatist rather than an ideologue, he was well suited to head Britain’s first coalition for 70 years. He formed a close working relationship with Nick Clegg, the Lib Dem leader and Deputy Prime Minister. The high point was their post-election love-in in Downing Street’s Rose Garden.

But Cameron showed his tribal side by defeating Lib Dem plans to replace first-past-the-post with the alternative vote system at general elections – an omen for the smaller coalition party’s fate at the 2015 election.

The five-year partnership was overshadowed by austerity, even though the deficit was cut much more slowly than Cameron and Osborne intended. But Cameron secured important reforms such as same sex marriage. His government introduced free schools and expanded Labour’s academy programme. It safeguarded the NHS, schools and overseas aid budgets and generously protected pensioners’ benefits while squeezing working age welfare. But the social reforms Cameron talked up in opposition fell victim to the austerity programme; it might have been better for him to be PM in better economic times.

His low point during the Coalition was a humiliating defeat in 2013 when he asked the Commons to authorise military strikes against the Assad regime in Syria.

Cameron and Clegg usually agreed to differ on Europe. Worried about Ukip’s threat at the coming general election and under constant pressure from Eurosceptic Tory MPs, Cameron promised an in/out EU referendum in 2013, a pledge included in the Tory election manifesto.

The Prime Minister had another near political death experience in 2014 when it appeared that the SNP-led Yes campaign was on course to win a referendum on independence. The No camp fought back and won but it was a narrow escape and Cameron would probably have resigned if Scotland had voted to break up the UK. Now a second referendum on independence is on the cards after Scotland was outvoted by England and Wales in the EU referendum, potentially undoing a key plank of Cameron’s legacy.

His next escape came at last year’s general election. Many people, including Cameron himself, did not expect the Tories to win their first overall majority since 1992, but they did after gobbling up Lib Dem seats and ruthlessly exploiting fears about an Ed Miliband-led government in the SNP’s pockets in a hung parliament. Writing a hastily-conceived victory speech rather than the resignation one he thought he would make, Cameron returned to his 2005 agenda and promised One Nation reforms to boost life chances. A raft of reforms were seen as his “bucket list” before he honoured his promise to stand down before the 2020 election. They were put on hold for the all-consuming EU referendum. Now Cameron will not get the chance to complete them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments