Extending diabetic eye screening to two years could risk sight loss, study finds

Researchers said ‘the incentive of biennial screening is to release capacity in the NHS’ and ‘lessen the inconvenience’ for diabetics at low risk.

Extending eye screening for diabetic people from every year to every two years could heighten the risk of blindness, researchers have said.

They also suggest the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) could help the NHS keep up with demand.

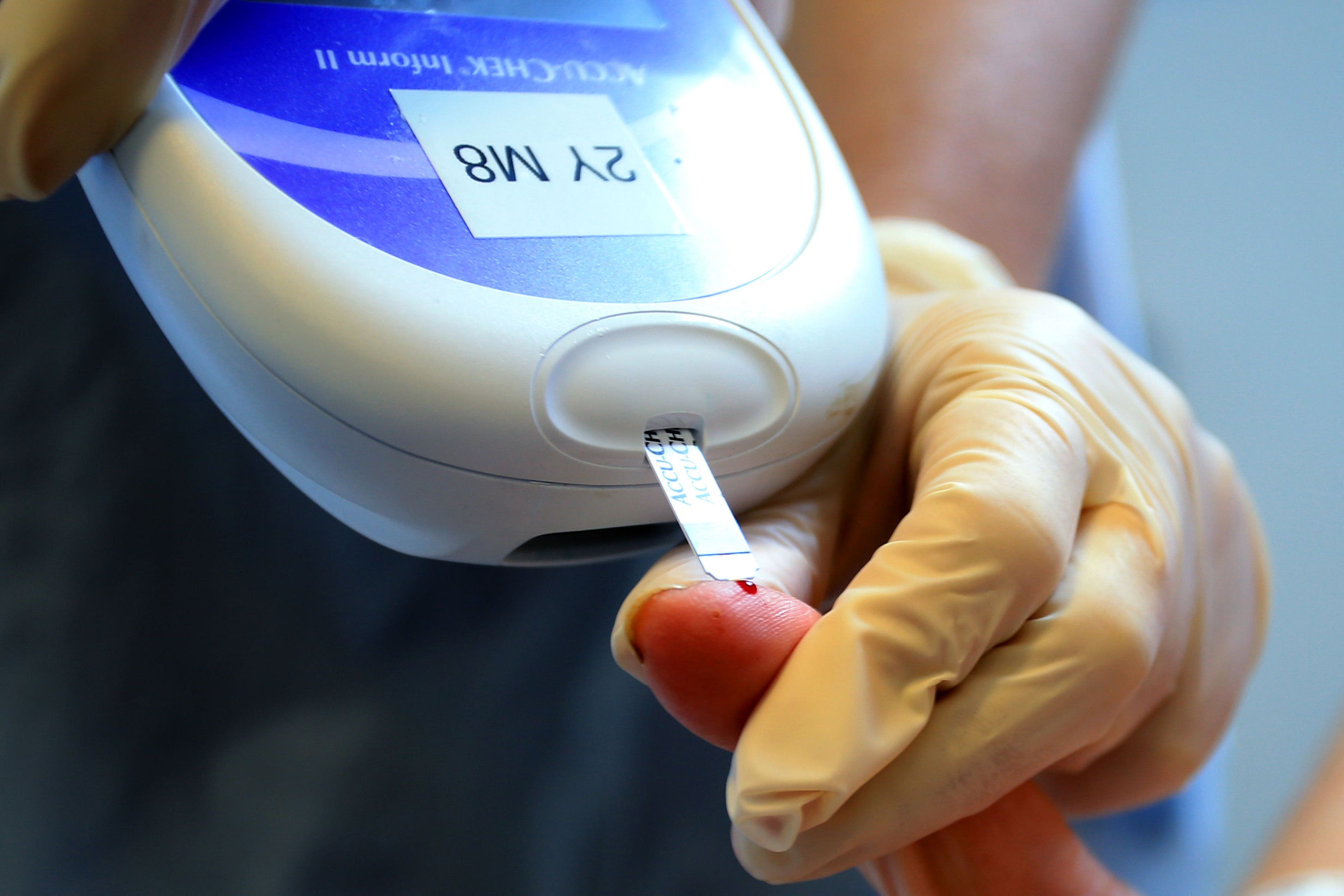

Eye problems – known as diabetic retinopathy – are a complication of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, caused by high blood sugars damaging the back of the eye.

Early intervention is vital to ensure there is no sight loss.

Since 2003, diabetics aged 12 or over in England have been invited for eye screening.

In October the guidance was updated, meaning those with no sign of diabetic retinopathy for two consecutive tests will be invited back every two years, while those at a higher risk will be screened more regularly.

However, a team led by researchers from Moorfields Eye Hospital said it is “not clear what clinical and other impacts this change might have”.

To explore the issue, they tracked the eye health of 82,782 people with diabetes in north-east London, who were screened between 2012 and 2021 and showed no sign of diabetic eye disease in two previous tests.

Of the cohort, 36% were white, 16% were black and 37% were of South Asian or other ethnicities.

Introducing a requirement to report by age and ethnicity for selected screening standards would enable regular, prospective monitoring of changes to service delivery, so disparities do not remain unrecognised

Over eight years they tracked the number of people that developed diabetic retinopathy, along with their ethnicity and age.

During the period, there were 1,788 new cases of sight threatening eye disease in patients regarded “low risk”.

Of the group, 103 people had the most severe type of the condition – proliferative, or PDR – which carries a high risk of blindness and requires urgent referral.

Researchers said, based on the figures, extending the annual eye check to two years would have delayed diagnosis by 12 months in 56.5% of people with sight threatening disease and in 44% of patients with PDR.

Analysis also showed men had lower rates of sight threatening diabetic eye disease than women, and those with type 1 diabetes had higher rates than people with type 2 diabetes.

Black people were 121% more likely to develop a severe form of the condition than white people.

Progression of diabetic retinopathy was also more pronounced among the youngest (under 45) and oldest (over 65) patients.

The paper, published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology, said: “The incentive of biennial screening is to release capacity in the NHS” and “lessen the inconvenience” for diabetics at low risk of sight loss of attending screening appointments.

According to Diabetes UK, there are about 4.3 million people in the UK with a diabetes diagnosis, but an additional 850,000 people could also be undiagnosed.

Researchers also suggested that “there is a need to address the potential to amplify ethnic and age inequalities in healthcare”, while AI could help the health service keep up with screening frequency.

In a linked editorial, Dr Parul Desai and Dr Samantha De Silva, of Moorfields Eye Hospital and the Oxford Eye Hospital and University of Oxford, respectively, called for “a review and update” of the NHS diabetic eye screening programme “to take account of the differential impact among subgroups of the population eligible for diabetic eye screen”.

They added: “Introducing a requirement to report by age and ethnicity for selected screening standards would enable regular, prospective monitoring of changes to service delivery, so disparities do not remain unrecognised, and provide information for responsive action on any unwarranted variation… because one size may not always fit all.”

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: “We’ve accepted the recommendation of the independent scientific experts at the UK National Screening Committee which was based on a wide study of existing evidence, including 25 independent studies.

“The evidence shows that if no sign of diabetic retinopathy is found, it is safe for individuals to be screened every two years. People who are at higher risk of sight loss will continue to be seen annually or more frequently as necessary.

“This change, which has already been implemented in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, will help the NHS improve the service it offers by reducing the number of appointments people with diabetes at lower risk need to attend.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks