Population-wide gene testing ‘limited in its ability to predict disease risk’

Experts say polygenic risk scoring fails to take into other factors that contribute to disease risk, such as smoking or deprivation.

Population-wide screening for variations in thousands of genes is limited in its ability to accurately predict the risk of developing a disease, experts have warned.

In an analysis published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), scientists have said that polygenic risk scoring, which is an estimate of an individual’s genetic susceptibility to a disease, fails to take into account other factors that contribute to disease risk, such as smoking or deprivation.

A group of experts from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, the University of Oxford and University College London (UCL), are calling for clarity on the expected benefits of this approach.

Lead author Dr Amit Sud, academic clinical lecturer in genetics and epidemiology at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said: “There is a huge amount of enthusiasm about polygenic scores, and they do have the potential to improve our ability to predict who will or will not develop a disease, albeit rather modestly.

“But we argue that the benefits and harms surrounding the use of polygenic scores are carefully evaluated before they are widely implemented.

“Given the majority of disease in a population occurs in people who are not at high polygenic risk, these scores should not detract from effective population-wide screening and interventions to address modifiable and impactful risk factors like smoking and socioeconomic deprivation.”

It comes as five million people in the UK are set to be offered polygenic scores, as part of Our Future Health, which is the UK’s largest research programme.

Through the NHS, these participants will be offered information on the risk of developing a disease based on polygenic scores, which in turn, will influence clinical decision-making and access to screening.

Meanwhile, the experts said that two recent Government reports have shown “marked enthusiasm” for polygenic scores in healthcare.

We argue that the benefits and harms surrounding the use of polygenic scores are carefully evaluated before they are widely implemented

They argue that large studies are needed to carefully evaluate the risks of polygenic risk scoring, which looks across thousands of variants in a person’s DNA to gain a collective assessment of the genetic risk of diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, or diabetes.

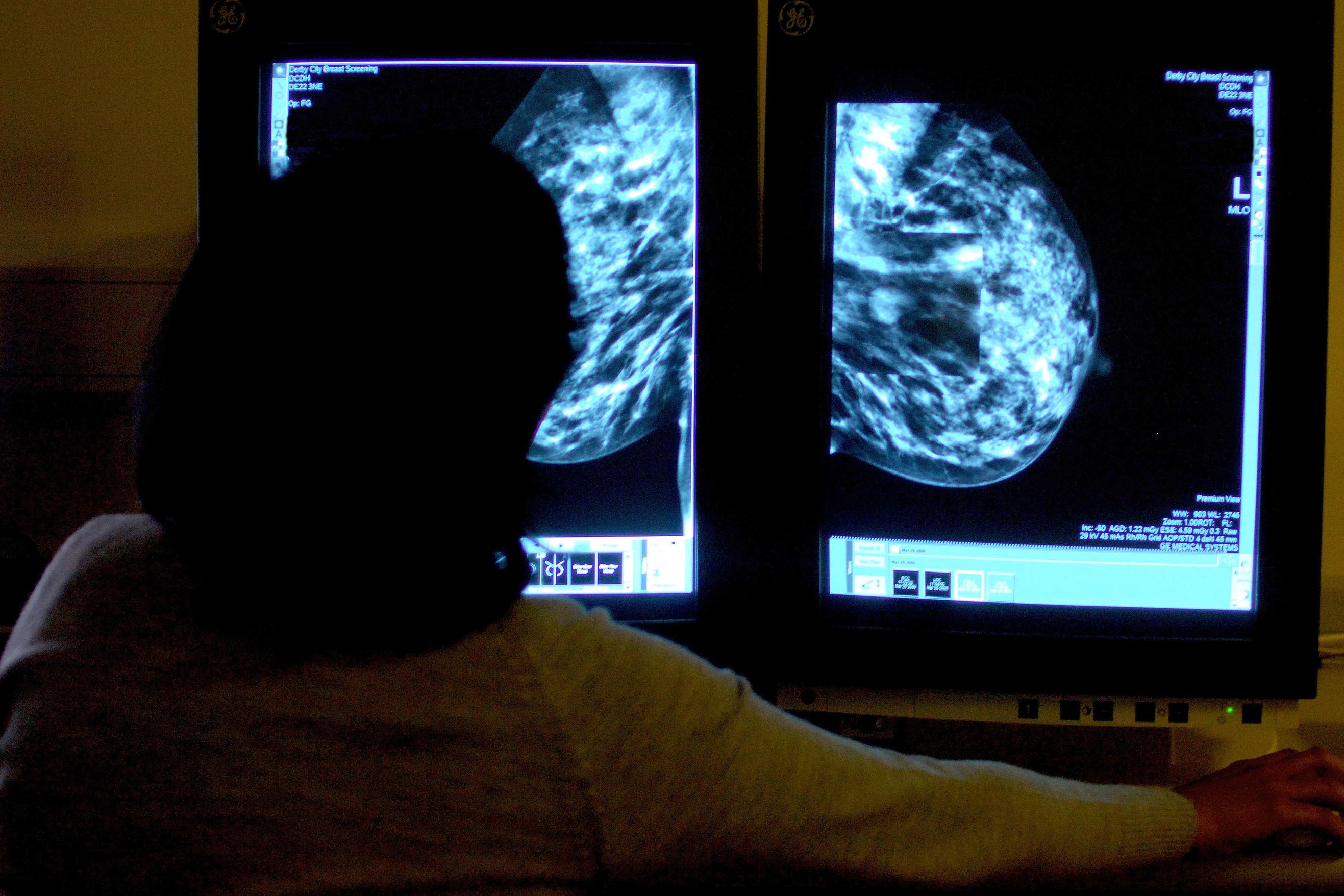

At present, this type of testing focuses on a small number of well-understood disease mutations – such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast and ovarian cancer – which can significantly raise the risk of developing those diseases.

But the experts said using polygenic scores to screen for people at risk of common illnesses such as heart disease or other types of cancer will miss the majority of cases in the population.

And in many cases, it would also involve a large number of healthy individuals undergoing invasive tests and therapies who will never go on to develop the disease, they added.

The scientists cite an example where the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) uses a 17% lifetime risk of breast cancer as the threshold for deeming women at “moderate risk”.

But in a polygenic risk score study – which also used this threshold – only 39% of women who will go on to develop breast cancer have moderate or high-risk scores.

This means the majority of breast cancer cases are missed using these scores, the scientists said.

Conversely, 22% of women who will not develop breast cancer will have a high polygenic risk score and will therefore be a “false positive”, they added.

Anneke Lucassen, professor of genomic medicine at the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Medicine, said: “Polygenic scores offer really important insights in research, but using them in screening programmes – or clinical care – is often less predictive than people might expect.

“Our research is a reminder that polygenic scores only measure a small proportion of overall disease risk, and should not distract from efforts to address modifiable risk factors for diseases.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks