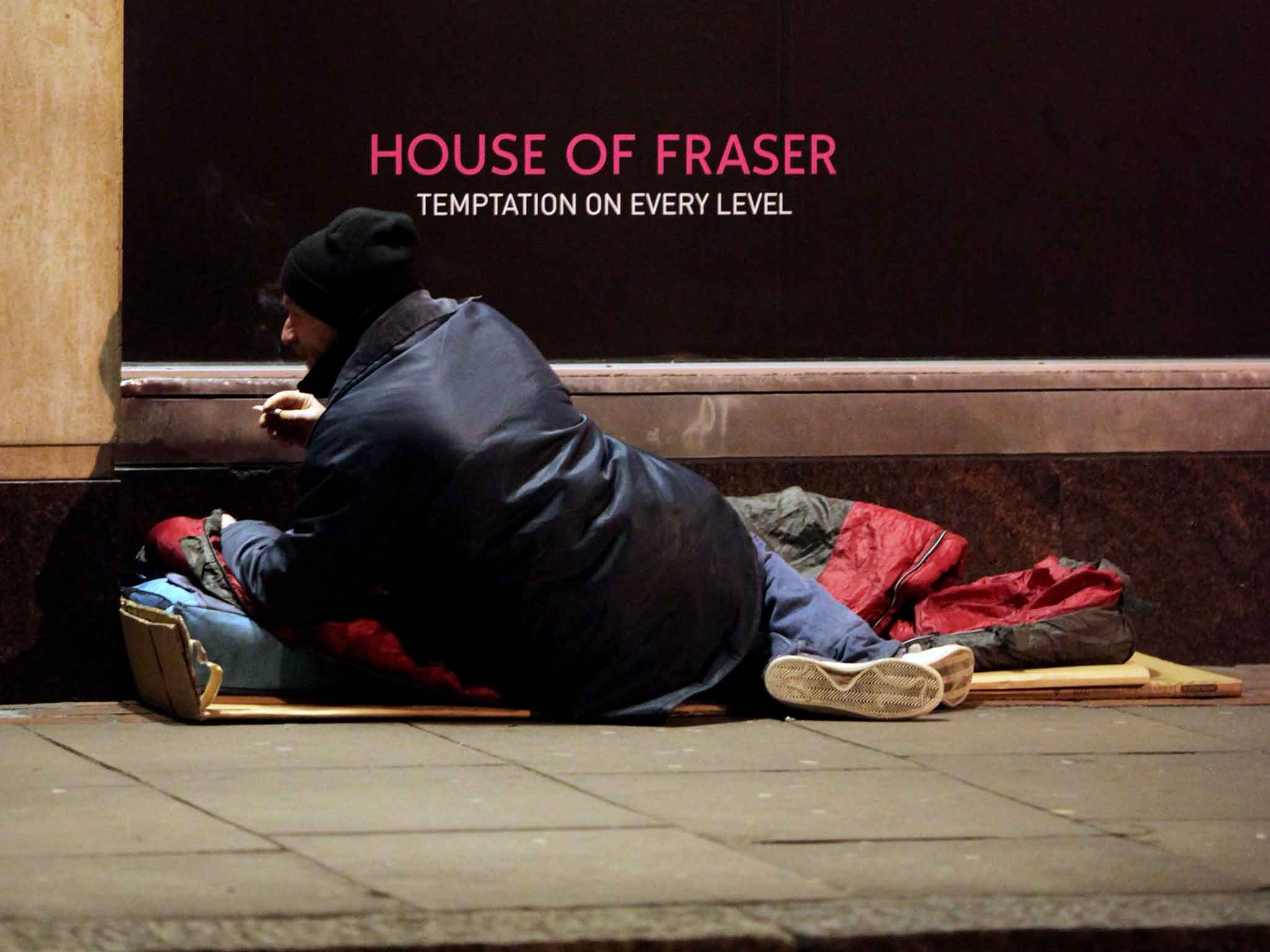

Youth homelessness figure eight times higher than Government admits, says charity

Exclusive: 136,000 young people aged between 16 and 24 in England and Wales sought emergency housing in the past year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The full extent of youth homelessness is more than eight times higher than the Government admits, according to a new report.

Some 136,000 young people aged between 16 and 24 in England and Wales sought emergency housing in the past year. The figure is based on an analysis by the Centrepoint charity of 275 Freedom of Information responses from local authorities. In stark contrast, only 16,000 young people were officially classed as “statutory homeless” – which would mean councils had a legal duty to house them – according to the report.

Worryingly, some 30,000 of those seeking help were turned away with little if any support. And as many as 90,000 were only offered support such as family mediation, to help them stay at home, or debt advice. This means the vast majority of those going for help are not getting the full assistance they’d be entitled to if they were officially accepted as being homeless.

“The most alarming aspect to these findings is that it is very likely they are a significant underestimate – many of the local authorities where youth homelessness is most prevalent did not respond to our Freedom of Information requests,” said Gaia Marcus, who runs Centrepoint’s youth homelessness databank.

Failures to assess the majority of young people in need of help mean some of the most vulnerable could miss out on the help to which they could be legally entitled, leaving them at risk, campaigners warn.

Only 40 per cent of young people in England were given an assessment to determine their eligibility for emergency housing in 2014, while in Wales fewer than two-thirds (60 per cent) were assessed.

The most alarming aspect to these findings is that it is very likely they are a significant underestimate

“A timely intervention in the lives of homeless young people enables them to achieve their potential in education, training or work. Unfortunately, too many young people are being failed at the first opportunity. It’s critical that central government provides sufficient funding to meet the true level of need,” said Ms Marcus.

“Each young person facing homelessness deserves to be given a thorough assessment to determine the help they need.

“No young person should be abandoned to dangerous situations at home or on the street.”

The Government needs to change the way it reports homelessness figures; all young people going for help should be assessed for their needs; and more funding is needed to enable councils to deal with the problem, says the report.

This comes amid warnings of a growing housing crisis. It emerged last month that homelessness has risen 40 per cent in five years, with more than 55,000 households accepted as homeless by their local council last year, according to the latest official statistics. The number of homeless families living in temporary accommodation in England stands at 50,750, the highest since 2008. Greg Clark, the Communities Secretary, warned in July that young people are being “exiled” from their local areas to “find a home that they can afford”.

In a statement, a government spokesman dismissed the report’s findings: “Centrepoint’s analysis is misleading and based on anecdotal evidence.” However, Matt Downie, director of policy at the Crisis homelessness charity, commented: “Our own research shows that when homeless people go to their council for help, all too often they are turned away to sleep on the streets.”

Peter Box, the Local Government Association’s housing spokesman, warned: “A chronic shortage of affordable housing and 40 per cent cuts to council budgets over the past five years means councils are facing real difficulties in finding emergency care for all homeless people.”

And Roger Harding, director of policy at Shelter, added: “It’s utterly shocking that any young person with nowhere to go would be turned away when they ask for help. But, sadly, our deepening housing crisis means this is becoming all too common.”

Case study: 'I was pushed out of my home because of who I was'

Keith Murray, 24, was a student from London who was thrown out of his home two years ago after his father refused to accept that he was gay. Official statistics fail to record anyone whose plight falls outside the narrow criteria for being homeless – for example, being under-18, being pregnant or a victim of domestic violence – which would force councils to help. Keith approached his local council for help, but was told he was not a priority.

“I was told that I could go on to the website and register for a bidding number for social housing. I did that, but I was never given a bidding number and I never gained any points. I was at the bottom of the list.

“I was vulnerable, I didn’t make myself homeless; I was pushed out of my home because who I was. Given a chance, I would have explained, but I didn’t get the opportunity, because you’re right there at the counter and there’s someone waiting next to you.”

He then managed to find a room in a safe house before getting a place at Centrepoint in London. “The staff have been amazing, they helped me in the right direction and I got back on track, because I lost myself for a moment there. The only thing left to do now is to move out and go back to uni.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments