Five years of visceral fear: How terror bred by Yorkshire Ripper made Seventies north the darkest of places

The shock caused by his brutal killings seeped into everyday life: ‘It was like living in a horror movie at times,’ recalls one journalist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In comments made shortly before the Yorkshire Ripper died on Friday morning, Richard McCann – son of the serial killer’s first victim, Wilma – offered a short but suitable epitaph: “He ruined,” he said, “so many lives.”

This is self-evidently true.

Peter Sutcliffe caused untold devastation for the friends and family of the 13 women he killed between 1975 and 1980.

But the shadow cast by the savagery of this one-time grave digger also goes far beyond the friends and family of those poor souls he murdered and mutilated.

Rather his crimes – random acts of sexually-motivated ultra-violence spread across a vast geographical area – caused a terror so visceral and so penetrating that it seeped insidiously into the daily lives of those living in the north and changed the behaviour of an entire generation.

Women would avoid going out at night. Those that did had dads or husbands meet them off buses. Men were stopped in their cars and questioned by police. Detectives urged everyone to consider anyone a potential suspect. Even the landscape itself became entwined with the horror: the crumbling cities, the de-industrialised wastelands and the still-new motorways – via which, it turned out, a man could commit murder in Manchester and still be back home with his wife in Bradford in time for bed.

It is not an easy admission to stomach but it is true nonetheless: the fabric of northern life was changed, perhaps permanently, by Peter Sutcliffe.

“Murders and sexually motivated murders have always happened,” says Tracy Powell, a journalist-turned-university lecturer who grew up in Sheffield at the time of the killings. “But I think women of my generation felt a lot less safe going out at night than those of my mother’s generation, who lived through the Fifties and Sixties. They were less carefree, and I think that was because of this. The night became something where there was danger.”

When Powell started going out as a teenager, she remembers, her dad would insist on dropping her at pub doors or friends’ homes and always waited to see her get into the building before leaving. He would pick her up at the end of the night. “That became the norm for a lot of girls,” the 53-year-old says.

This was, it is worth stressing, an era not short on bad news: the Troubles, the miners strikes and the three-day week all darkened the age.

Yet even so, the cloud created by the Ripper – who attacked his victims in Huddersfield, Halifax, Leeds, Bradford and Manchester – was one that hung especially dreadful.

In the days and weeks after fresh slayings, or even fresh case developments, town and city centres would lie half-deserted in the evenings as people were reminded anew of the peril. Police would set up random road blocks in a desperate – and flailing – effort to catch their man. Entire swathes of the male population, including Sutcliffe himself, would be interviewed as suspects.

So pervasive, indeed, was the sense of danger that compares at working men’s clubs would finish the night off by telling the women to make sure they travelled home with someone they trusted.

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say it felt at times like you were living in a horror movie,” says Stephen Booth, a journalist-turned-crime writer who worked on newspapers across Yorkshire, Greater Manchester and North Nottinghamshire between 1974 and 2001. “The nights drew in and, out there in the shadows – and no one knew where – there was a bogeyman who might take away someone you loved. It sounds like fiction but it was happening to us.

“I don’t mean you constantly walked around in a state of fear but it was there, a sort of low-level sense of unease, always in the background.”

He himself remembers a conversation with his wife Lesley in which she questioned him about his own whereabouts.

At the time, he was working days on the Holme Valley Express newspaper in West Yorkshire and doing night shifts across the Pennines in The Guardian’s Manchester office. One victim’s body had been found close to where the couple lived in Chorley in 1977. When they moved to Holmfirth a couple of months later, another victim turned up just a few miles away in Huddersfield.

“She said to me, ‘All these nights when you say you’re working shifts, I only have your word for that, how do I know what you’re doing?’” the 68-year-old recalls today. “It was a strange conversation to have with your wife – a new wife too – but it didn’t feel unreasonable. I understood because that paranoia was everywhere. For five years, we lived with that.”

Later, he became one of thousands of men stopped in their cars.

“I’d been drinking as you did back then,” he says. “But they weren’t bothered. My wife was with me and they asked her if she knew me and was safe with me; all the questions they asked her.”

It is well documented that it was police incompetence – and no little institutional misogyny – that probably meant the killings went on longer than they should.

Time and again evidence was ignored or not cross-referenced. Hoax letters threw the investigation off course. A sense pervaded that officers did not take the early murders seriously because they believe the Ripper was only targeting sex workers.

But it was also the times that allowed the Ripper to evade justice.

Without mobiles and CCTV, the shadows he stalked were longer and lonelier. It is obvious but worth saying that people in the Seventies were not a phone call away. The only way loved ones could generally be reached was when they walked in through the front door. Arriving home late became an agony for those waiting.

“It changed the way life was for a lot of people, right across the north of England,” says Bob Westerdale, a crime reporter who worked on local newspapers in Greater Manchester, Lancashire and South Yorkshire from 1975. “My mum, when the winter drew in, she’d no longer walk to the shop at night for a pint of milk or loaf of bread. She just wouldn’t.

“It had the exact same effect that the Moors murders had on kids a decade earlier. There were children terrified of going to the fair on their own. This was the same for women. They essentially had restrictions forced upon them because there was this tw*t out there.”

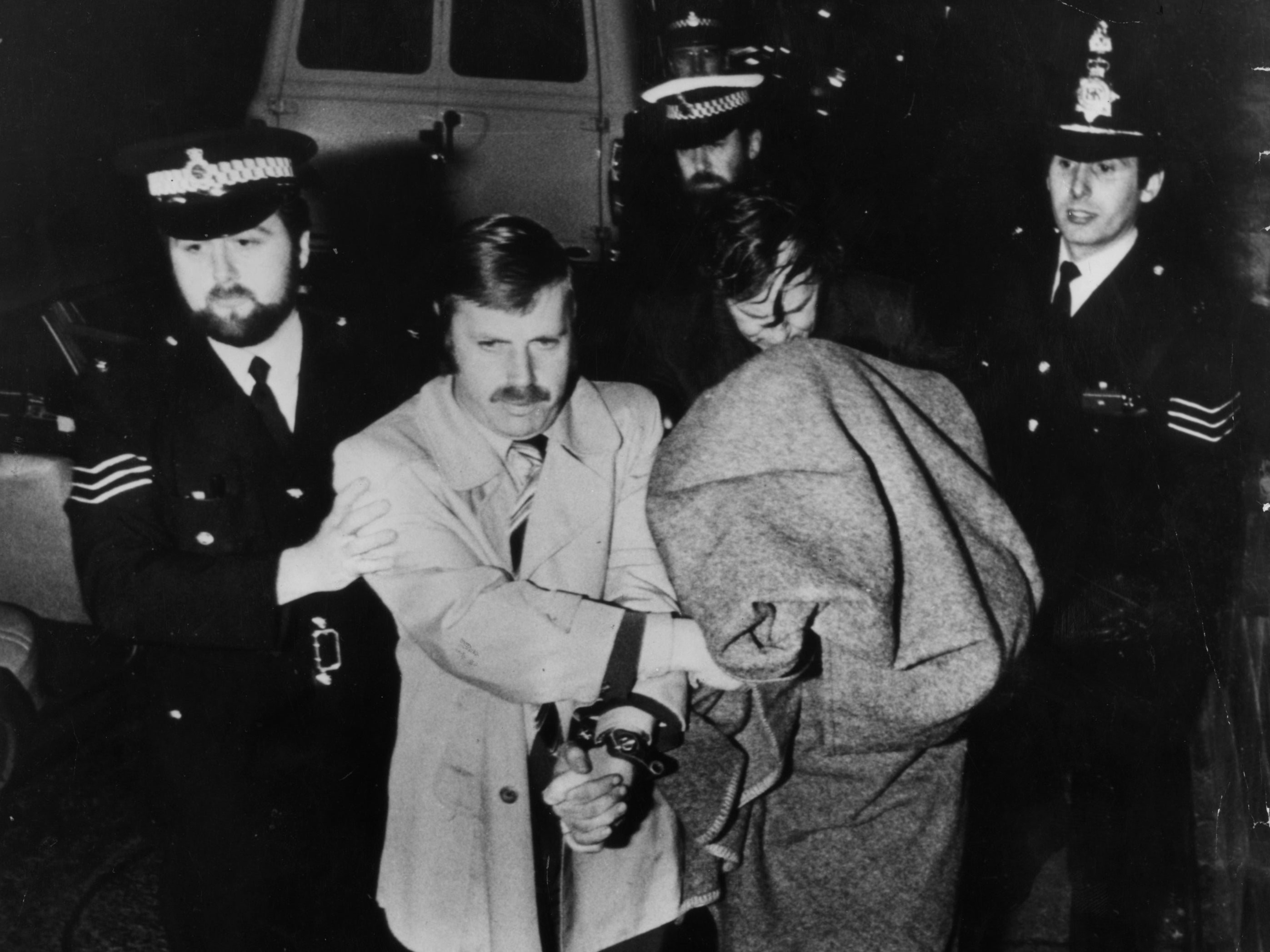

The night Sutcliffe finally confessed after being caught in Sheffield in 1981, there was inevitably an outpouring of relief. Such was the hold he had had on the public consciousness that crowds gathered to see him being taken to court in Dewsbury. Acclaimed author David Peace, whose Red Riding novels were heavily influenced by the case, remembers bunking off school to go.

But, says Sheron Boyle, the relief was mixed with anxiety.

She was a Wakefield student at the time but would go on to write extensively about the case, interviewing everyone from Sutcliffe’s family and his victims’ relatives to the police who worked the investigation.

“I remember we all sat round watching the news that night,” the 60-year-old says. “It was what we’d been waiting for… It was a relief, a huge relief.

“But did it make us feel safe? I’m not sure. He wasn’t out there anymore but fear doesn’t just disappear, I suppose.”

Westerdale agrees. “My mum never changed,” the 64-year-old says. “She never went out for milk at night again. Not even after he was locked up. He’d raised the possibility in people’s minds that this could happen, in Manchester, in Yorkshire, anywhere; all it needed was a copycat.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments