Yorkshire Ripper ‘denied call to wife to say goodbye before he died’

Peter Sutcliffe was restrained with chains in the hours before his death and was unable to directly contact his next of kin.

A report into the death of serial killer Peter Sutcliffe - well-known as the Yorkshire Ripper - has found he was not able to call his wife before his death with Covid-19.

Sutcliffe died on 13 November 2020 at age 74 at the University Hospital of North Durham and he was restrained with chains for many hours before, according to a report by the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman.

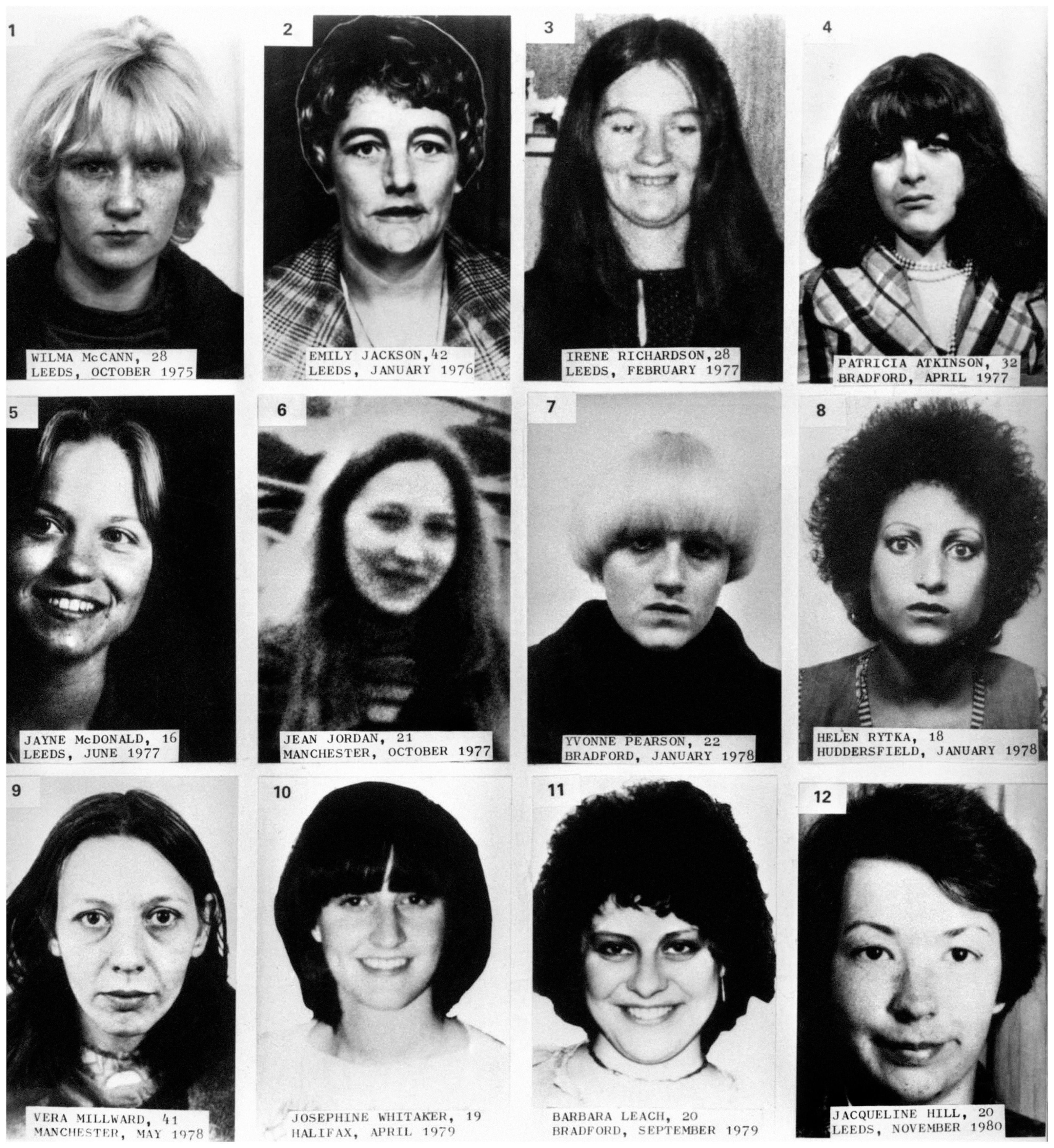

Sutcliffe, who later changed his name to Peter Coonan, was sentenced to life imprisonment for murdering 13 women and attempting to murder seven more in Yorkshire and north-west England between 1975 and 1980.

He was an inmate at high-security prison HMP Frankland in Durham since 2016, previously spending much of his sentence at Broadmoor psychiatric hospital.

He had several long-term physical health conditions including Type 2 diabetes, impaired vision, angina and paranoid schizophrenia, according to the report. When asked if he wanted to ‘shield’ on a different wing due to his health issues, Sutcliffe declined.

On 20 October 2020, Sutcliffe went to hospital to be urgently fitted for a pacemaker for a heart block and days later on 5 November, he tested positive for Covid-19. He is believed to have caught the virus in hospital.

His condition deteriorated over the course of a few days, and on 9 November he was taken to hospital then again on 10 November. For both visits, Sutcliffe was restrained with an escort chain.

When it became clear Sutcliffe was going to die, it then took four hours for officers to gain permission to remove his restraints and it was a further hour before they were finally taken off.

Sutcliffe was also not able to talk directly with wife when he was dying, with prison staff acting as messengers between them.

Sue McAllister, who wrote the report, said that while the care Sutcliffe received in prison was equal to what he would have received in the community, there were some concerns for how long it took the inmate to return to prison after a hospital visit, the delay in removing restraints and in the lack of contact with his next of kin.

Ms McAllister said: ‘I am concerned that, on one occasion, a local hospital discharged Mr Coonan back to Frankland, yet it took nearly eight hours to obtain a secure vehicle and he arrived at the prison at 1.45am.

“I am also concerned that managers in the Category A Team made decisions about the use of restraints based on limited input from healthcare staff about Mr Coonan’s current condition and mobility.

“In addition, it took too long for escorting officers to remove the restraints after a manager had granted permission to do so.”

Ms McAllister added: “The Prison Service has a duty to protect the public when escorting prisoners outside prison, such as to hospital. It also has a responsibility to balance this by treating prisoners with humanity.”

The report recommended better liaisons between hospital trusts and prison staff, for assurance that decisions on removing restraints are communicated and made quickly and that staff formally consider whether a terminally ill prisoner should be allowed direct contact with their next of kin.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks