'They expected to be welcomed with open arms': Inside the remarkable lives of the Windrush generation

Exclusive: New book tells of hopes, fears and dreams of those making journey from Caribbean to UK – and what the reality was like when they arrived

When I told children at school my granny was Jamaican, I was met with disbelief; sometimes – understandably – mixed with laughter. Slap bang in the middle of Hackney, the secondary school had a considerable Caribbean contingent and the kids were clued up about Jamaican culture, but my granny’s trajectory did not fit into their narrative.

Jamaica is far more of a melting pot than many who have never been there imagine. While being a country in which the majority of people are black, with most Jamaicans being the descendants of enslaved Africans transported to the region by European colonisers, it is also home to small but significant Chinese, Indian, Jewish and Syrian/Lebanese communities – the latter being part of my granny’s heritage.

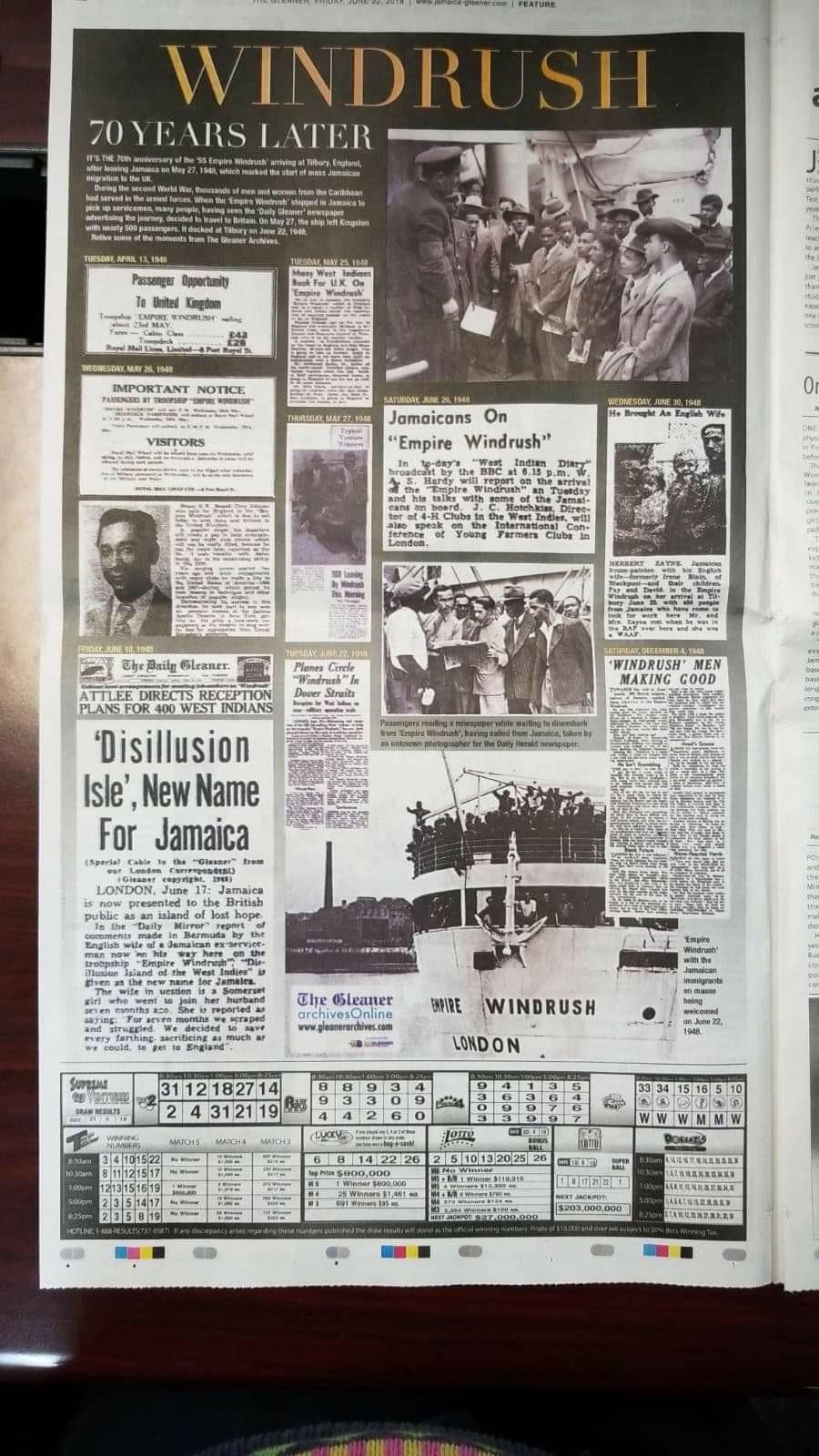

Joyce Elisser Norris, now the ripe age of 90, came to the UK from Jamaica via boat in 1948, armed with two trunks of clothes, books and other belongings. My granny’s story has now been memorialised in a new book titled Mother Country: Real Stories of the Windrush Children, which explores the epic journey and subsequent lives of the Windrush generation.

While she was not on HMS Windrush itself, my great uncle was – something we did not discover until earlier this year.

“I uncovered the fact my great uncle had travelled to the UK on the HMS Windrush in 1948 with his wife from a tiny clipping in an old Jamaican newspaper,” my sister, Naomi Oppenheim, explains in a chapter in the book.

“I read it on 23 June, a day after the 70th anniversary of the ship docking at Tilbury. Following almost a year of work on an exhibition about the Windrush generation for the British Library, Songs in a Strange Land, it was very emotional to realise that I had a tangible link to this particular boat.”

Empire Windrush is best remembered for carrying one of the first large groups of postwar West Indian immigrants to Britain – bringing 1,027 passengers and two stowaways from Jamaica to London in 1948.

“For the pioneers of the Windrush generation, Britain was ‘the Mother country’,” states the book. “They made the long journey across the sea, expecting to find a place where they would be welcomed with open arms; a land in which you were free to build a new life.”

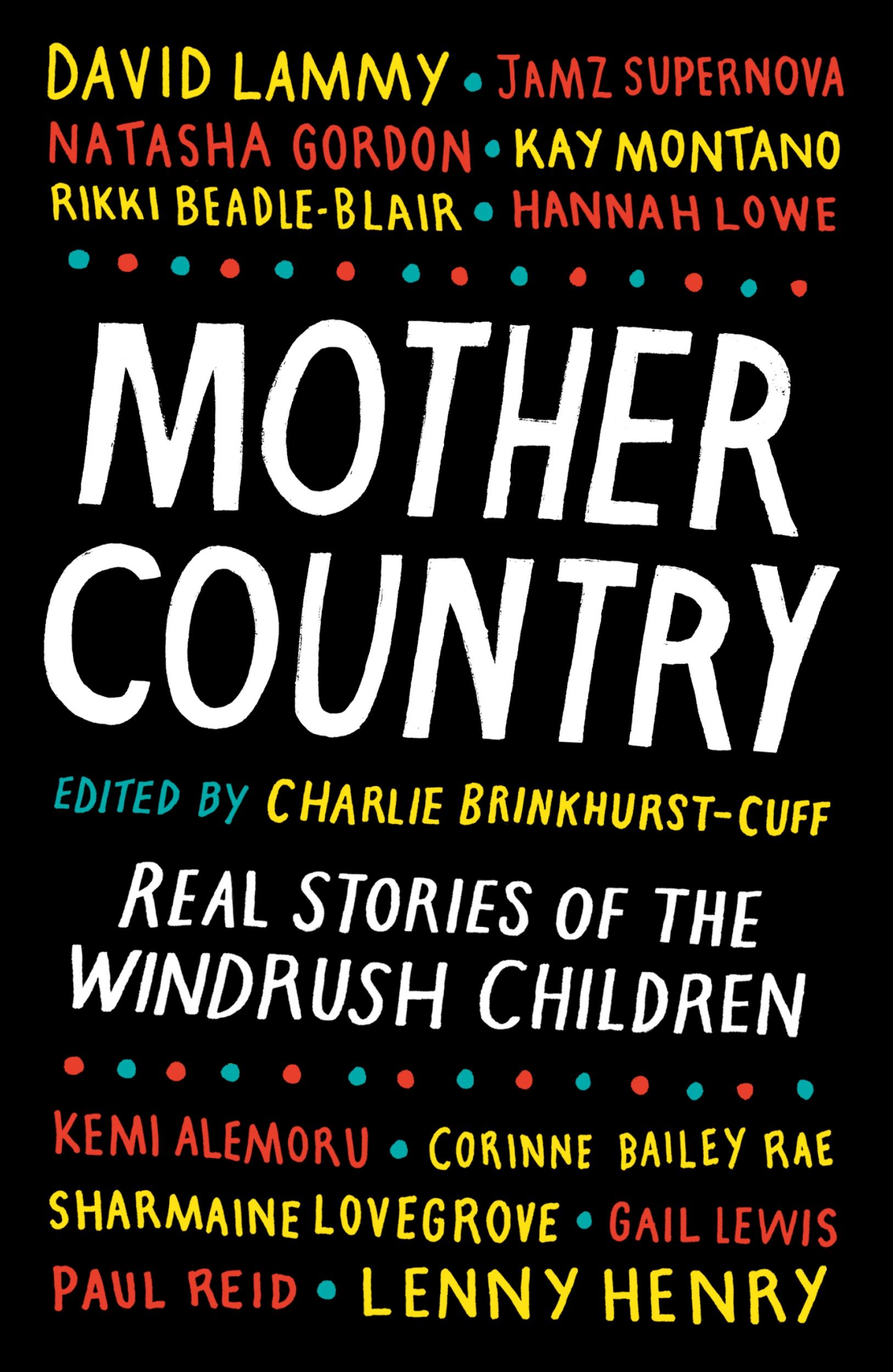

The book explores the reality of their experiences and those of their children and grandchildren – comprising 22 life stories which span more than 70 years and include contributions from the likes of Sir Lenny Henry, David Lammy and Corinne Bailey Rae.

Lammy, the Labour MP for Tottenham who was born in the constituency to Guyanese parents, says the story of Windrush has been neglected in the media.

“The Windrush generation is not a homogenous group. It is made up of hundreds of thousands of different stories,” he tells The Independent. “Mother Country brought together a diverse range of voices – from politicians to actors, writers, comedians, singers and more – to share a few of this generation and its ancestors’ many and varied perspectives.”

While there has been a great deal of attention around the Windrush scandal – which broke earlier this year after it emerged people had been wrongly detained, denied legal rights, threatened with deportation and, in 63 cases, may have been wrongly deported from Britain by the Home Office – there has been less attention on the diverse stories of the Windrush generation itself.

Lammy, who has spoken out about the Windrush scandal, Grenfell Tower, police brutality and BAME people in the criminal justice system,says: “This is about taking back agency. It’s about telling our own stories rather than having them told for us.”

Many of those involved had been born British subjects and arrived in the UK before 1973 – particularly from Caribbean countries.

Sir Lenny says he had found the process of recounting his family history for the book “cathartic”.

“I was keen to be involved in this book because even though my mum came over to the UK from Jamaica nearly 10 years after Windrush – the story of Jamaican migrants moving across the shining sea to begin new lives resonates,” he says.

“My mother was the pioneer of our family. She arrived in the UK with very little money but with a heart full of ambition and dreams. She did three jobs, found somewhere to live and arranged for the rest of the family to make that same trip.

“Mum had to adapt when she came here – she thought everyone would know who Jamaicans were and where Jamaica was. In the first week she was here, some young men followed her down the street asking her where her tail was. Not such a great welcome.”

He argues diaspora stories deserve attention – saying books such as these help to “level the playing field”.

“I hope the book helps the reader – whoever they may be – to empathise with these storytellers. The best writing draws us in and mesmerises us as we listen, learn and feel what we are being told,” he says. “The hope is that if we share these tales, the audience can walk a mile in our shoes and experience what it is like to uproot, journey thousands of miles away and then take root elsewhere and begin again.

“Hopefully this book makes it clear that Windrush was a convenient vessel on which to hang a movement, but unfortunately those that came before tend to get marginalised – ‘there weren’t any black people in Britain before the Windrush’ – and those that came after get lumped in with everyone else. So this is a good time to reflect on everyone who came, their trials, tribulations and triumphs.”

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff – who curated and edited the book – says a lot of the people she spoke to had never recounted their stories.

“It was not a regular thing for them to talk about their histories,” she says. “While there is a lot of dialogue around the Windrush scandal, the intricacies behind the stories are not well known. A lot of them are more complex and painful and joyful than people realise. I think the book does a good job of showing that.”

The author – a columnist of Jamaican-Cuban heritage who is deputy editor of popular feminist magazine Gal-Dem – says the book includes discussions around colourism and class, and tries to build on narratives not routinely associated with the Windrush generation.

“The book looks at how women’s narratives around Windrush have not been highlighted, and why they should be. Women migrated in larger numbers than men in the Windrush generation. This is a subtle part of history that people do not understand,” she says.

“It also looks at LGBT narratives which are rarely explored and community family ties, and obviously the impact of immigration. Also, Windrush was not the beginning of our story in the UK and not the end of it either.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks