Stonehenge: Origins of those who built world-famous monument revealed by groundbreaking scientific research

Experts have discovered act of cremation actually crystallises a bone’s structure and allows its origins to be detected – something previously thought to be impossible

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new scientific research collaboration is, for the first time, revealing who built Stonehenge. The cutting-edge study sheds a remarkable light on the geographical origins of the Neolithic community that first constructed the ancient site.

Complex tests carried out on 25 Neolithic people who were buried at or following the time of the initial construction of the now world-famous monument, have revealed that 10 of them lived nowhere near Stonehenge, but in western Britain, and that half of those 10 potentially came from southwest Wales (where the earliest Stonehenge monoliths came from).

The other 15 could be local to Stonehenge, Wiltshire-origin individuals, or the children of other descendants of migrants from the west. All the remains were cremations.

Up until now, it has always been assumed that it was not possible to carry out place-of-origin tests on burned bones – but recent research at Oxford University by Belgian scientist, Dr Christophe Snoeck of the Free University of Brussels, has now discovered that the act of cremation actually crystallises a bone’s structure and prevents the crucial origin-indicating isotope evidence from being contaminated by isotopic signals in the surrounding soil.

The cremated remains from Stonehenge of the 10 individuals of probable western British origin, were buried at various stages between the 33rd century BC and the 28th century BC.

Half of them (mainly from the 33rd-30th century BC) were probably from west Wales, while others (mainly from the 30th-28th century BC) were probably associated with places between west Wales and Gloucestershire. It’s likely that they were a roughly even mix of males and females and that they were of high social status. In all the cases, it is not known whether the individuals died shortly before all or parts of their cremated remains were transported to Stonehenge – or whether they were revered ancestors who had died several generations earlier.

Although the geographically intermediate examples hint at there being a well-worn prehistoric land route between west Wales and Stonehenge, nobody yet knows exactly how the stones (and the cremated remains) were transported. Sea and land routes are both possible.

The most likely sequence of events suggested by this and other research spans literally thousands of years.

Long before Stonehenge itself was built, the area had become ceremonially and ritually important by at least 4000BC.

The site had at least one or two large natural sarsen stones which may have been used as a focus for pre-Stonehenge ritual activity.

By at least 3500BC, elites from western Britain (or at least with western British, potentially south Welsh, connections) began to be associated with the developing sacred landscape of the area.

Then in around 3000BC, western British people (from southwest Wales) further developed their links with the Wiltshire area, by transporting dozens of large stones (and the cremated remains of many of their dead) from southwest Wales to a site they had earmarked for the creation of the first version of Stonehenge.

Archaeologists now believe that the stones may well have originally been from a stone circle or other monument in southwest Wales which was entirely “uprooted” and transported some 200 miles to Wiltshire and re-erected as a stone circle there.

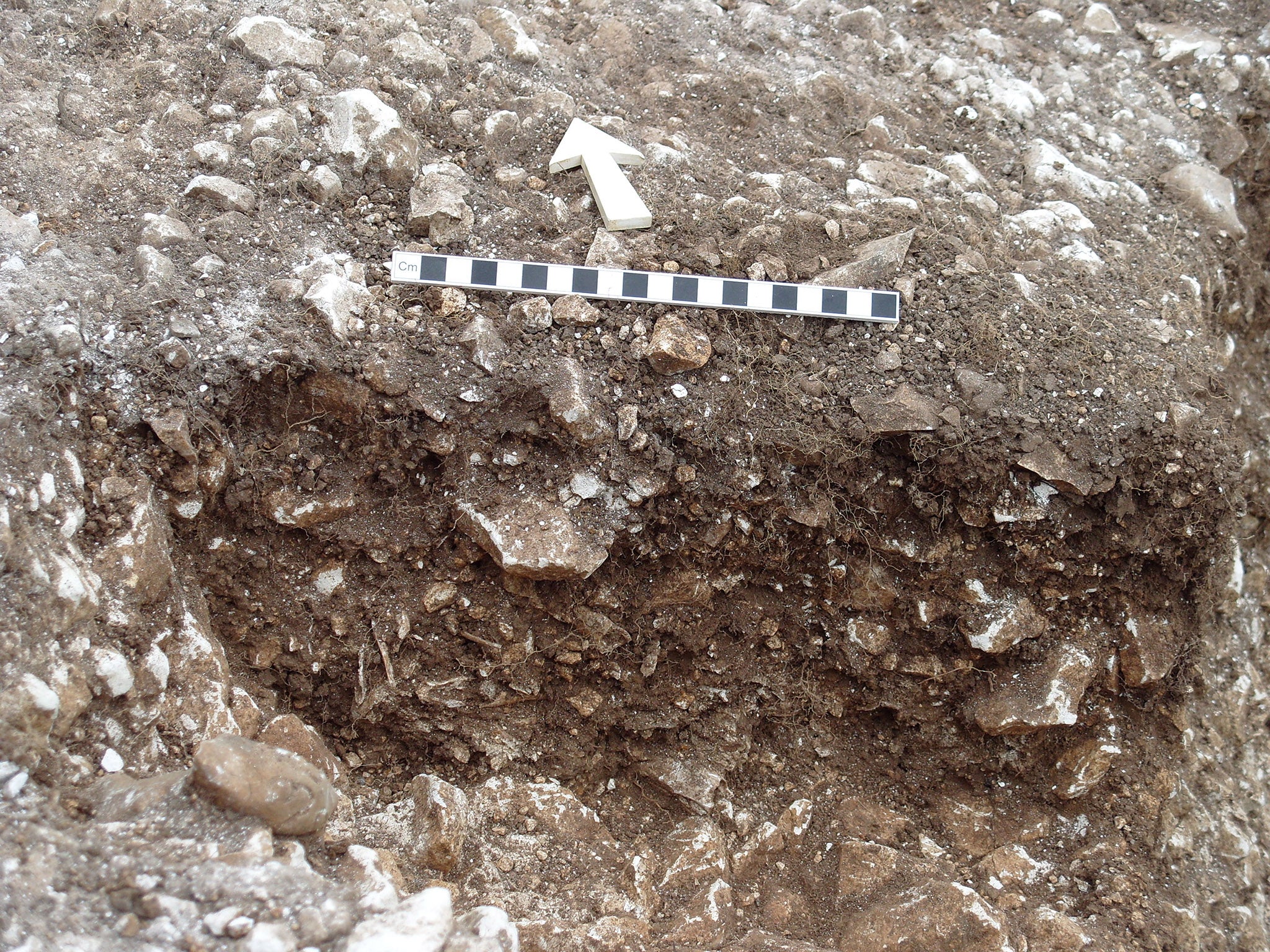

The recent scientific analysis of the Stonehenge cremated bones (that appear to have been buried adjacent to the newly re-erected stones) is now helping to reveal the origins of the community, which appears to have actually built the earliest version of the monument.

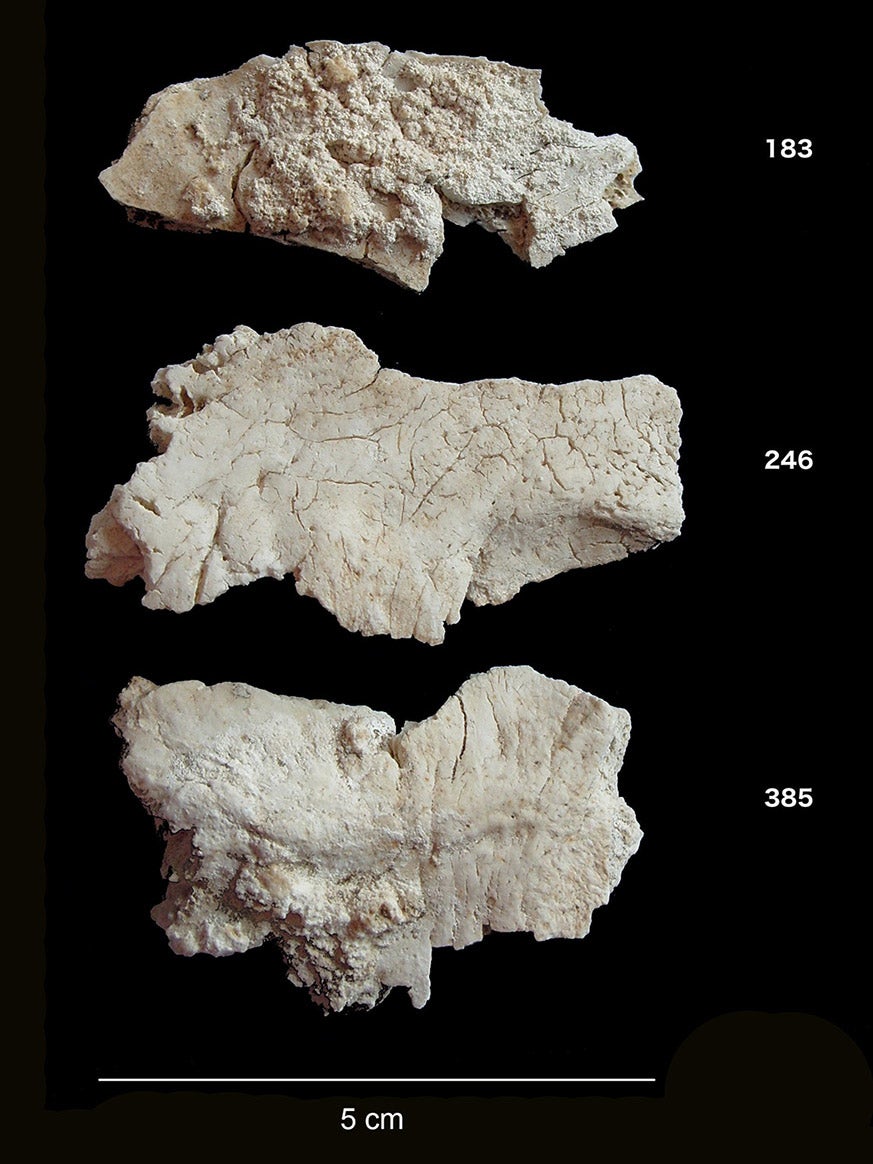

It is the strontium and carbon isotopic signatures in the cremated bone material that suggest a western British origin for the 10 individuals – and definitely not from the Stonehenge area. The carbon signal, absorbed into the bones from the timber used in the funerary pyre, also suggests a Western or non-local origin.

Geologically, previous research has shown that the stones (so-called bluestones or dolerite, used for the early phase of Stonehenge) also came from western Britain (in this case, the Preseli mountains in southwest Wales). Archaeological investigations have now pinpointed the quarries they actually came from – and when they were quarried (some time between the 34th and the 32nd century BC).

“The new isotopic evidence shows the scale and frequency of interactions between communities hundreds of miles apart,” said one of the project’s leaders, John Pouncett of Oxford University’s School of Archaeology.

“In the past, the research focus at Stonehenge has mainly been on the stones themselves. Now we are beginning to make tremendous progress in understanding the people and the community which built Stonehenge,” said the project’s osteologist, Christina Willis of University College London’s Institute of Archaeology.

The research was carried out by archaeologists and other scientists from the University of Oxford, UCL, the Free University of Brussels, and the Museum of Natural History in Paris and is being published today by the online journal Nature Scientific Reports.

The ever-increasing body of evidence suggesting Stonehenge and the original Stonehenge community’s western British origins has substantial implications for our understanding of British prehistory.

Firstly, it demonstrates the extremely broad geographical horizons that the builders of Stonehenge had. It shows that, despite agriculture increasingly tying people to the land, at least certain sections of society were well travelled and almost certainly had family connections spread across thousands of square miles.

Secondly, it shows the lengths that prehistoric people were prepared to go to achieve seemingly non-utilitarian objectives – i.e. the realisation of spiritual or ceremonial aspirations.

Thirdly, it suggests the possibility that the western origin of Stonehenge was so important and memorable that it was celebrated across the millennia through collective memory and epic storytelling passed on across the generations. Potential evidence of this is the Arthurian story of the magician Merlin, who transports the stones of Stonehenge from the west. The Merlin story describes how the stones came from Ireland – but southwest Wales is certainly close enough to Ireland, and also has important Irish connections. The story was first written during the medieval times – but may well have had its roots in prehistoric collective memory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments