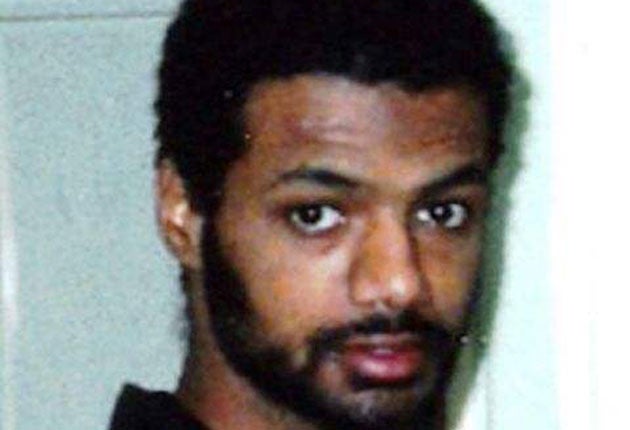

What lies ahead for Binyam Mohamed?

As the Guantanamo detainee returns to Britain, Richard Osley looks at the uncertainties he faces in adjusting to normal life after years of imprisonment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He will no longer have to wear the orange jumpsuit that has been his garb for the past four and a half years. It is just one small adjustment among the myriad changes that Binyam Mohamed will cope with as he leaves incarceration in Cuba for a future of fear and uncertainty.

The former Guantanamo Bay prisoner is due to fly into RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire tomorrow. Instead of being raced to an interrogation by anti-terrorism officers, he will almost certainly to be taken to hospital. At some stage, the 30-year-old will answer questions, but there is little prospect of any charges being brought. This week, his medical condition will be the chief priority.

Recently described as “just skin and bones”, Mr Mohamed has been left looking emaciated after a five-week hunger strike. A doctor will sit next to him throughout the flight home. He has paid a heavy price for his freedom: it was refusing food that sharpened the focus on his claims of torture at the hands of US authorities, the conditions at Guantanamo and his lack of opportunity for a legal appeal. Any “evidence” of links with terrorist groups, he said, was forced out of him in a “dark prison” in Kabul and a torture chamber in Morocco before he was sent to the prison camp in Cuba.

His release was confirmed by the Foreign Secretary, David Miliband, on Friday night.

By late tomorrow or early Tuesday, Mr Mohamed is likely to be free for the first time since he was arrested at Karachi airport in 2002, while allegedly using a false passport. Although born in Ethiopia, he was given leave to stay in the UK in 1994 as a teenage asylum-seeker. His travels to Pakistan and Afghanistan – explained by him as an attempt to get away from a bad circle of friends in London – led to US suspicions that he had been involved in al-Qa’ida training camps and a “dirty bomb” plot to attack America. Mr Mohamed denies the claims, and says he was abused during his detention: the alleged torture included cutting his penis with a scalpel and hanging him in the air by a leather strap.

He is reluctant to go to hospital. He will need psychiatric help to readjust to a world without eye masks, barbed wire, handcuffs and armed guards. Lord Carlile, the Lib Dem peer who has led an independent review of the UK’s terror laws, said yesterday: “I would expect a light and gentle touch to be applied to ensure that he is given every opportunity, subject to law, to integrate himself back into British society. There is no doubt he has suffered.”

Mr Mohamed will follow in the footsteps of eight other British residents who have been released from Guantanamo. Moazzam Begg, a bookseller from Birmingham who spent nearly three years in the camp without ever being charged, wrote a book about his harrowing experiences. But he is exceptional in his resilience against the mental scars inflicted in the prison.

Other former inmates have looked to blend quietly back into everyday life. “There is no rehabilitation programme, nothing as far as the Government is concerned, which helps to reintroduce this person into normal society,” Mr Begg told a radio interviewer. “In the case of somebody who returns to this country where he has no family members, it’s going to be doubly difficult.”

Mr Mohamed is said to want to get to “somewhere quiet”. It is unclear where he will stay, and there could be legal action over his right to stay in the country. He has no family here: his brother and sister live in the US. And he has a lost touch with many of the friends he made while studying.

Kate Allen, from Amnesty International, said last night: “The immediate focus should now be on providing medical and other support for Binyam.”

Mr Mohamed’s lawyer, Clive Stafford Smith, said: “He wants to go somewhere extremely quiet and have nothing to do with anyone. Binyam wants nothing more than to return to normal life in Britain.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments