Welsh devolution? A cry from the valleys, for the nation Britain forgot

Everyone’s talking about devolution: for Scotland, the North, even England. But what about Wales? As the principality’s nationalists gather in Llangollen, Jon Gower speaks up for a marginalised culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We’re lucky to have the celebrations of the Dylan Thomas centenary on Monday to lift our collective spirits as it’s been a bit of a difficult year to be Welsh. Mine’s a bitter.

It started miserably enough when the rugby team won only scraps at the Six Nations table, even if they did play with more vim and vigour against South Africa during the summer Tests.

Our health service, particularly the Welsh Ambulance Service, seems itself in need of emergency resuscitation. This is a devolved responsibility, with the Welsh Government ultimately in charge of 999 response times, so the seemingly parlous state of health care gives newspapers and gleeful politicians across the English border plenty of anti-devolution, or, more precisely, anti-Labour ammo. Which, in turn, gives First Minister Carwyn Jones conniptions.

Then we had the Nato conference in Newport which taught us how to identify all manner of whizz-bang helicopters, but, despite the spectacle of seeing the entire industrial-military complex on parade, not all the flags were out. Historically, Wales has been a markedly pacifist country. It was, after all, one of the most religious countries on earth, in the heyday of the chapels.

When Joseph Goebbels heard the word “culture” he memorably said he reached for his gun, to which a Welsh historian later replied that, in Wales, when we hear the word “gun” we reach for our culture, or at least our folk costumes. Not that culture’s that high on the political agenda nowadays: the Welsh Government recently downgraded the culture minister to a junior post and slashed the Arts Council budget.

We’ve often looked to Scotland for inspiration, in anything from Trainspotting to home rule. During the summer we looked far north with awe. The effect of the national conversation that galvanised the whole of Scotland in the months before the referendum threw some of us Welsh further into the doldrums, underlining an apparent lack of hunger at home for independence. Subsequent polls suggested little appetite for secession. Plaid Cymru – holding its annual conference in Llangollen this weekend – did see a surge in membership, but nothing like the tsunami of applications that flooded SNP HQ.

Wales has come a long way since the days when an entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica read “For Wales, see England.” Yet the problematic and often co-dependent relationship with its more powerful and influential neighbour across Offa’s Dyke, was thrown into savage relief by the autumn’s historic events the other side of Hadrian’s Wall. Scotland the brave seemed to sum it up. We watched from the sidelines. We were sidelined.

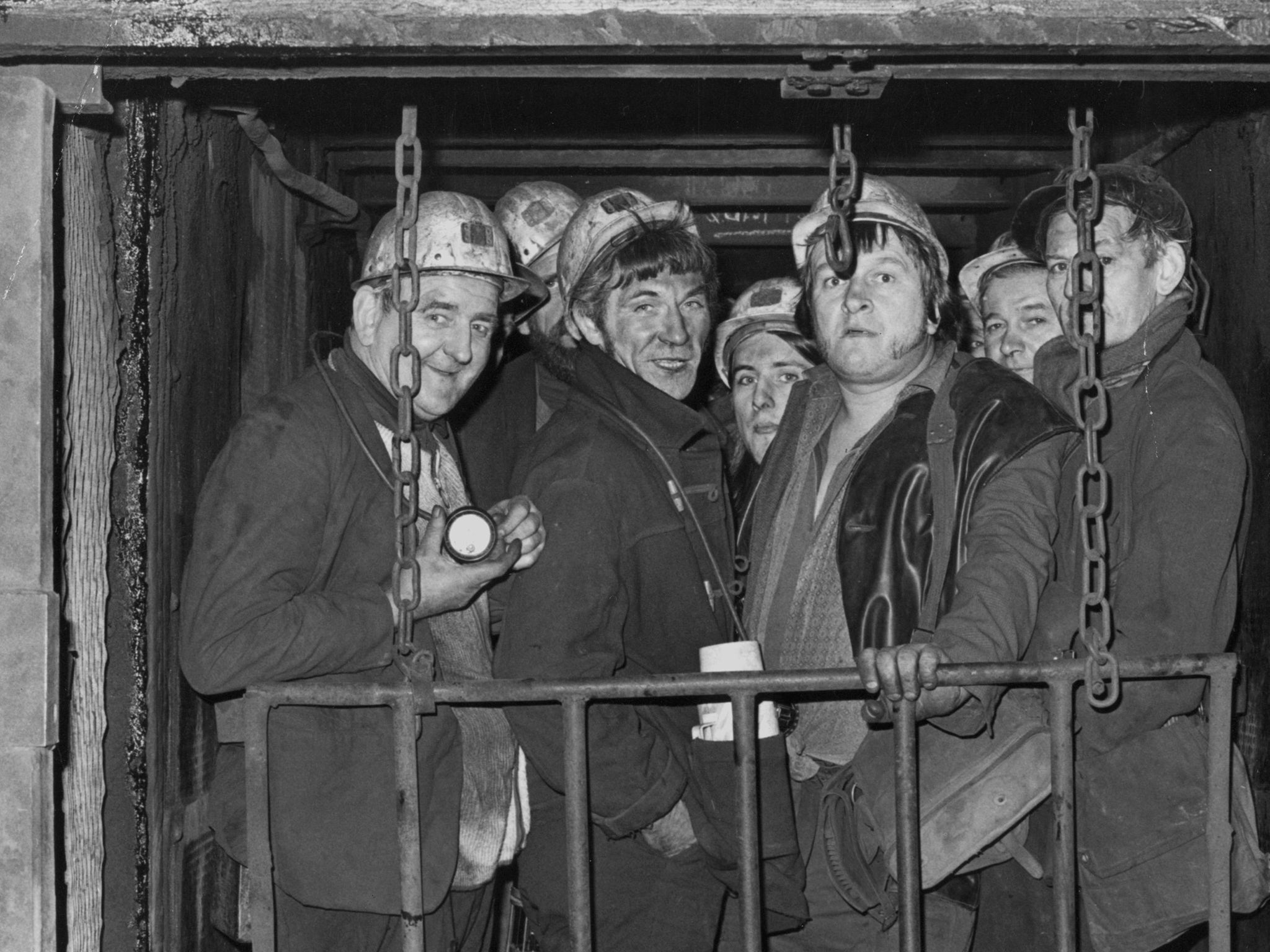

The fervid debate about whether or not the Scottish economy could float free on a lagoon of North Sea oil served to remind us that Wales doesn’t have the same natural resources, now that the coal’s been hewn and the water rights sewn up. Yes we have wind, and a fair bit of political hot air, but, in truth, nowhere near enough a plenitude of alternative energy to make a proper fist of it. There was a feeling that we couldn’t afford to go it alone, even if people wanted to.

For there’s no getting around it: Wales is a poor country. At one time there were more than 200,000 people working in the coal industry. Now we have more than 200,000 children living in poverty, which, in turn, leads to fewer qualifications, lower-paid jobs and often truncated lives. And it’s not just bad nutrition and poor education: it affects all aspects of life. Many Welsh kids have never seen a film in a cinema. Ever.

What the hell happened? A country that used to be a net exporter of teachers and had an incredible respect for education – with miners giving hard-earned pennies to create libraries and welfare institutes – now faces the spectre of growing illiteracy. It is a genuine scourge.

In some places – often in the most disenfranchised and disadvantaged areas in the country – 40 per cent of 11 year olds fail to reach the required numeracy and literacy targets. It’s come to a pretty pass when charities such as Save the Children have to campaign to improve matters, to ensure access to what is essentially a basic human right, to read. And this in a country where they’re lopping off branch libraries at an alarming rate

Which is perhaps why we need a Dylan Thomas celebration to shake out the glums. Just for a day. To celebrate fine words and writing, which is, in a sense, only a consequence of reading. Look at any great author: you’ll find a great reader. Dylan was both.

So it’s already been a whole, dizzying year of Dylan-mania, with a scheme called “Dylanwad” – which sent writers into schools to enthuse about his work – plays, art installations, TV programmes, publications and, of course, the occasional devotional pub crawl, not just in Wales but in Manhattan and London’s Fitzrovia too.

Yet Monday’s culmination of the Year of Dylan Thomas, the self-styled “Rimbaud of Cwmdonkin Drive”, may well divide readers. Some see him as a sad sack, scrounger and dedicated dipso who made a living out of passing out. His admirers view him as a hugely dedicated and hard-working artist who fashioned both gloriously euphonious verse and precision-engineered prose. He also conjured into being that fabulous cast of characters who live out their lives under Milk Wood – including Rosie Probert, Captain Cat and the Reverend Eli Jenkins – in his much-loved “Play for Voices”. I like to think that as we celebrate the 100th birthday Dylan never had, we’re actually toasting language itself, in all its tumult, range, ambivalence and glory.

In Wales we have a language other than English that is itself cause for raising a glass or three. While languages worldwide become extinct at the rate of one every fortnight, the persistence, steeliness and resourcefulness of the Welsh language and its 600,000 speakers is miraculous.

In Wales today they simply can’t build the Welsh language schools fast enough. We have Welsh TV, radio, books, theatre, festivals and speakeasies. It’s a living language, though the migrations of Welsh-speakers into the cities have weakened the heartlands in the west and north of the country.

Half a century ago I attended the first Welsh language primary school in Wales, Ysgol Dewi Sant in Llanelli. Our class numbers were minuscule. My daughters, Elena and Onwy, nine and five, now go to Ysgol Treganna, a new, purpose-built school on the outskirts of Cardiff, which boasts 500 pupils and is just one such school among hundreds.

We’ve come a long way. There was a time when, had either of my daughters spoken Welsh in school, they’d have had to wear a punishingly heavy piece of wood around their necks proclaiming the words “Welsh Not.” Census returns, decade on decade, showed a haemorrhage of speakers. The prospect of language annihilation was real. So the fact that demand for Welsh language education now far outstrips supply is a genuine case of language resurrection. Not that the picture’s entirely rosy. The last census showed some distressing dips, including in cities such as Cardiff.

In the rich, nutritious linguistic soup that is the English language there are words floating around from pretty much everywhere: “bungalow” from the Hindi, “yoghurt” from Turkish, “anorak” from the Inuit. And there’s a smattering of Welsh words, too, such as “corgi” (“small dog”), “eisteddfod” and, debatably, “penguin.” But there’s one Welsh word that hasn’t made it into the OED because it’s well-nigh untranslatable, and that is “hiraeth”. It’s a kind of aching longing for something lost, or absent, like the Portuguese “saudade”. It’s a melancholic nostalgia, perhaps, for the days when Welsh rugby forwards moved like Panzer divisions and mercurial backs ran rings around their opponents. Or perhaps a longing for a time, very long ago, when Welsh, in its early Brythonic form, was spoken all over these isles, as far north as Scotland, where the name Strathclyde derives from the Welsh “ystrad clud”, just as Dover comes from “dwfr”, the Welsh word for water, or the Avon in Shakespeare’s Stratford has its origin in “afon” meaning river. It’s the etymology of something lost, a long time ago.

Another word that has no equivalent in English is “cynghanedd”. It’s a very old system of arranging strict metre poetry, described in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, no less, as “the most sophisticated system of poetic sound-patterning practised in any poetry in the world”.

Dylan Thomas might not have been a Welsh speaker – but his great-uncle Gwilym Marles was a dab hand both at speaking it and at conjuring “cynghanedd”. Dylan’s collected poems have much the same lilt and lift as Welsh language verse, written by such writers as great uncle Gwilym who mined their own, ancient language – in Wales’s senior tongue, after all – for metaphor and meaning. And Dylan had his fair share of “hiraeth” too – for childhood’s innocence, for a far-off, better time, say at Fernhill, where the “owls were bearing the farm away.”

In this centenary year we can all claim some part of Dylan: the roistering poet, the hard-working fashioner of undying verse, the toper, the bore, the velvet-voiced broadcaster, the short story writer, determined compiler of acrostic and cryptogrammic verse, the war years’ political propagandist, the nostalgia-drunk celebrant of childhood Christmases, the US touring lecturer and the vaudevillian in the groves of academe, the playwright, the lover, the pantheist, the Swansea boy. All these and more.

This year he’s also a convenient grail for Welsh literary tourism, being one of the most famous Welshman, after all, up there with Tom Jones and Ryan Giggs. He is, in some strange way, a sort of validation for the rest of us Welsh, for our romanticism and fondness for ale. He’s also one of the three famous, poetic Welsh Thomases, standing higher in the pantheon than Edward and RS, possibly because Dylan has the Cuban heels of celebrity. He should also be a poster boy for the pleasure of literacy, and how a book can even buy you a pint.

But for me, most of all, here was a supreme wordsmith, conjuring up and calling into being – like some beery Celtic shaman – a whole euphonious world, with his incantations and descants, his easy lilts and glorious songs. Yes, those songs, which soar like skylarks, making high the sky. Thomas’s hyper-romantic view of Wales helps mask some of the harsh realities of living here, in this country of sheep and fish, castles and three million splendid stories.

Jon Gower is author of “The Story of Wales” (BBC Books, £6.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments