UK regions hit by brain drain: Exodus of talent to London adds to fears that recovery is geographically skewed

For Britain to prosper, cities must prosper. They are engines of growth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Huge numbers of young adults move to London from Britain’s other cities and never return home, according to a report revealing the extent to which the capital drains talent from the rest of the country.

The research underlines the capital’s dominance over the national economy, showing how it accounts for the vast majority of jobs created both in the private and public sectors in recent years.

The findings will reinforce fears that the gathering recovery is skewed towards the South-east of England, with the rest of the United Kingdom struggling to share its benefits. Vince Cable, the Business Secretary, recently warned that London is “becoming a giant suction machine, draining the life out of the rest of the country”.

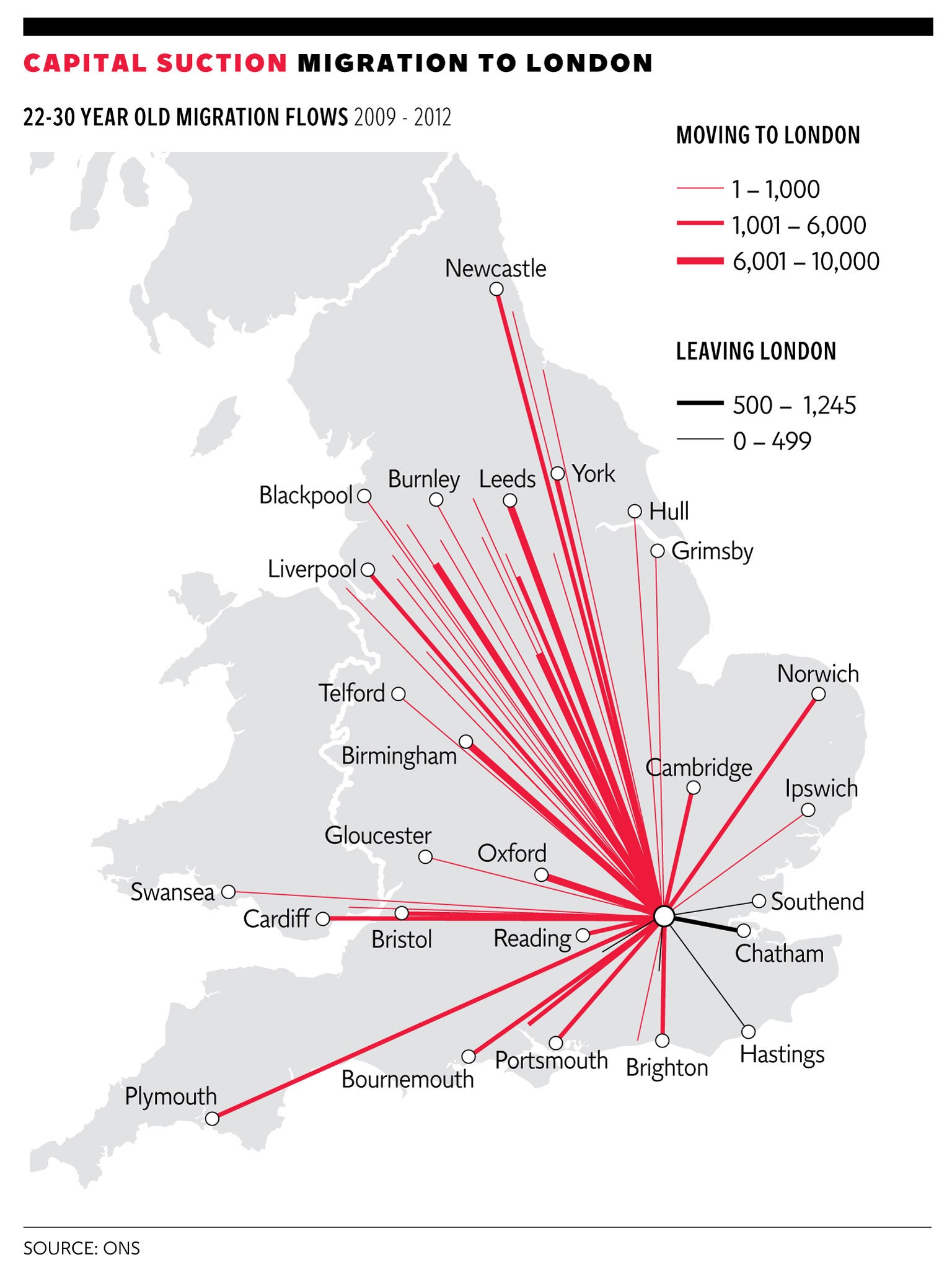

The Centre for Cities says the gap is widening between the capital and other major centres of population, and that urgent action needs to be taken to help boost economic growth in other large cities. In its annual “health check” of British cities, the think-tank discloses there is a major exodus from other parts of the UK once students graduate from university, with one in three 22- to 30-year-olds who change city heading for London. Eighty-thousand people in that age group moved to the city between 2009 and 2013, compared with 31,600 who left London – a net inflow to the capital of 48,400.

Its research finds that people begin to move out again when they reach their thirties, but only to surrounding counties such as Essex, Kent and Sussex.

“While these people may no longer live in London, they very much remain within commuting distance, and commuting patterns suggest that some are likely to remain part of the capital’s labour market,” the Centre says.

It also shows the capital powering far ahead of other cities in generating employment. More than 215,000 private-sector jobs were created in the capital between 2010 and 2012, four-fifths of the total for the whole of the UK. And for every public-sector post created in London, two were lost in other cities.

The Centre argues that London remains Britain’s “economic powerhouse” and pivotal to the nation’s success, but adds that other cities needed to be given powers over spending and investment similar to those enjoyed by the capital.

In its report, Cities Outlook 2014, it says there are “green shoots” of recovery elsewhere. It names Edinburgh as the second most successful city in generating private-sector jobs, followed by Birmingham and Manchester.

Liverpool has experienced a welcome fillip with the creation of 12,800 jobs, some in publishing, which have offset public-sector job losses.

At the other end of the scale, Bristol is still recovering from heavy redundancies in financial services, while Glasgow, Bradford, Sheffield and Blackpool have suffered job losses in public and private sectors.

Alexandra Jones, the chief executive of Centre for Cities, said: “London is leading the recovery and its long-standing economic strength continues to attract talented workers. London’s strength is a huge asset but we need to make the most of our other cities’ economic potential.”

The report says: “The data indicates that London does appear to suck in talent from the rest of the country. But rather than this being a problem of London’s dominance, the more pertinent question appears to be: why aren’t other cities offering people enough opportunity to stay – and what can be done about it?”

It calls for major cities to have more power and funding devolved to them. The Centre argues that Greater Manchester and Greater Leeds each produce more than the entire Welsh economy, but have none of the powers enjoyed by the Cardiff Assembly.

Ms Jones said: “Devolving more funding and power to UK cities so they can generate more of their own income and respond to the different strengths and weaknesses that Cities Outlook 2014 highlights will be critical to ensuring this is a sustainable, job-rich recovery.”

Cities Minister Greg Clark said: “For Britain to prosper, our cities must prosper. They are the engines of growth for the national economy in a world where cities are increasingly competing against others around the world.

“That is why the City Deals programme, which began in 2012, has been so important, giving cities more power to drive growth, something from which London has benefited for more than a decade.

“The Centre for Cities report uses data up to September 2012, and illustrates exactly what the Government was saying at the time – that it is essential to hand powers over to cities so that they can take control of their own destinies. Since then, the cities have gained momentum.”

Case study: the entrepreneur who headed south

Andrew Sheldon, 34, owns a technical graphic design company. He was born in Greater Manchester and moved to London after graduating in architecture in 2001. Having lived in London for nearly a decade, he and his partner, Christine, moved to the Home Counties in 2012.

"I have fond memories of my time in Manchester and built strong ties there, having grown up and been educated at one of the country’s best schools.

“But studying architecture saw me spend many years in London and Brighton, where I met Christine. Both of us talked about returning to Manchester but found ourselves inadvertently laying roots in the South: making friends, scoping housing and securing business contacts.

“It wasn’t until we had our first child in 2008 that we reconsidered it – this time attracted by the prospect of family childcare and a cheaper cost of living. But the financial crash made that impossible: there were more business prospects in the South and we’d both just started our own businesses and needed the work.

“So we moved to north London and, in 2012, when things looked better economically, we moved to a bigger place in St Albans. Having had our second child last year, we now intend to remain here for at least 18 years.

“As well as nurturing new friends – some of whom have made similar decisions – we have also noticed a lot of local business prospects in the area, which has come as an unexpected surprise.

“Of course the cost of living is higher in the South but there is peace of mind knowing you are just 20 minutes from the heart of London.

“I’m glad to see signs of a regional recovery and hope it continues– but I would need to see more long-term evidence of economic growth in the North before I could seriously contemplate returning there.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments