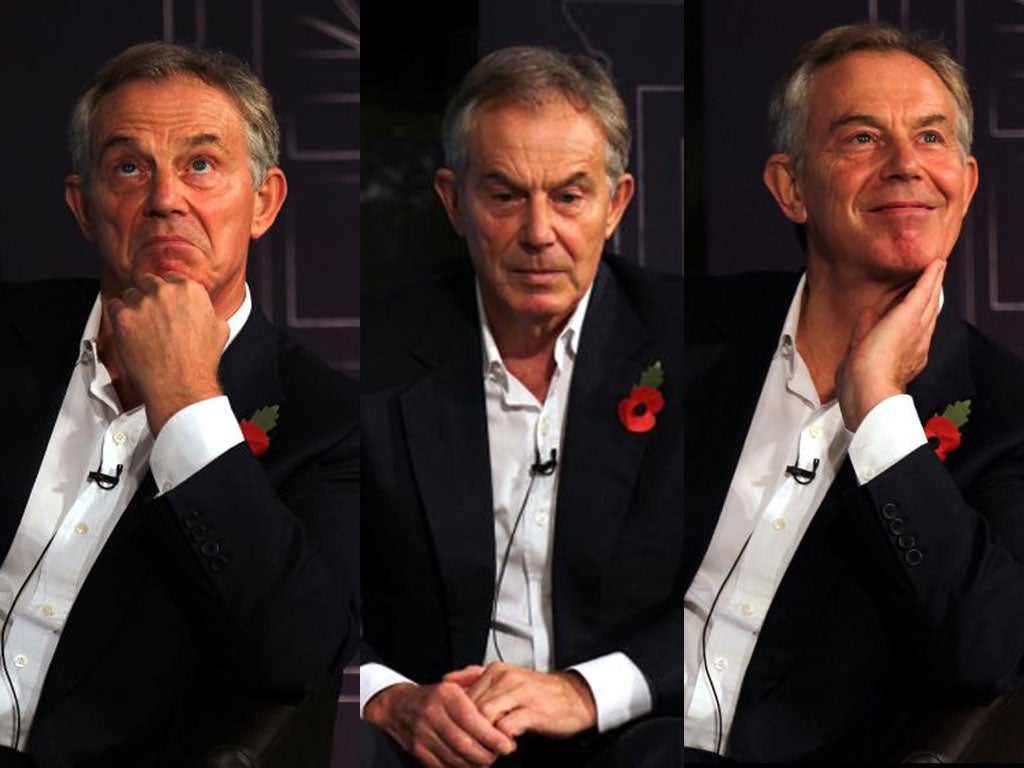

Tony Blair: How I became Prime Minister of the world

The former Prime Minister is now advising the governments of now fewer than 20 countries, he revealed in a Q&A chaired by The Independent’s John Rentoul. So which successes – and failures – of his years in office can they learn from?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.JOHN RENTOUL: Jack Straw said that he thought that the Prime Minister had too much power in the British constitutional system, and I was hoping you would respond to that.

TONY BLAIR: I learnt a lot in government, and I’ve learnt a lot since leaving government. The kind of journey of being in government is that you start at your most popular and least capable, and you end at your most capable and least popular. And that transition is really all about the education: about what government today is about. And since leaving office – I mean, by the end of this year there will probably be 20 different governments in different parts of the world that myself and my team will cooperate with. And with most political leaders the challenge they face today is not so much one of ideology, not so much to do with issues of honesty or transparency, although that is an issue in many countries, and the media tends to focus on that, the challenge is the challenge of efficacy: how do you get things done?

What happens in our system is that you have no transition, you just win the election and go straight in there. And what happens is that the tradition is that the civil servants all line up on either side of room. And the tradition is the outgoing Prime Minister goes down the line, and everyone says goodbye, and then a new guy comes in and everyone says hello. So they applaud the new person in. Well, we’d been out of power for 18 years, so I came in and I was going down the line and lots of people were crying. So you got to the end of the line and suddenly feel guilty about the whole thing. And then I came into the Cabinet Room, and I remember sitting there: the only person in the room was Robin Butler who was the head of the civil service at the time. And I remember he just motioned me into the chair opposite him, and said. ‘Well done.’ And then he said, ‘Now what?’ And the ‘now what?’ is the single most difficult thing that you have to then answer, and the ‘now what?’ is a lot harder today because of the fact that you are changing legacy systems that have grown up around the public sector over many, many years. And that is hard: really hard. And it requires, in my view, a quite different skill set from what’s gone before.

This is what political leaders face today. And it isn’t a question of whether, you know, the civil service is good or bad, it’s that the world has changed so fast, and is changing so fast, that if you don’t change the way that you govern you just become somewhat redundant and irrelevant. And, in my view, the root of cynicism about politics is a lot less to do with a lot of the issues people often talk about; it’s to do with the fact that you’ve got an electorate today that’s far more assertive about their own individual circumstances, and yet they still think that government works in a very old fashioned way.

So that’s the nature of the challenge, and that’s what I found, and that’s what I think is fascinating to work on. But round the world today, the reason why what we talked about in government finds such an echo, is that all these governments have exactly the same problem.

And so the moment I’m talking to another leader in the world today, it’s like a light switching on the moment you talk about this, because they know that’s their problem. And so, if you’re in a poor African country, or an emerging market country in the Far East, you know you’ve got to get the electricity switched on, you’ve got to get roads built, you’ve got to get your basic reforms done around things like agriculture, and doing business. Getting the quality advice and implementing is what it’s all about.

JR: Are you on Twitter?

TB: My office is on Twitter. I don’t tweet myself – at least, not intentionally, but I probably should do. It’s one of the most difficult things today in politics is that there’s such noise generated around you and around your decision making, I think it’s really hard for a political leader to take a step back and work out what is real and what isn’t. I sometimes get political leaders who’ll say to me, ‘You want to see what’s happening on Twitter around such-and-such.’ And I say to them, ‘That may be real, and it may be representative, or it may not. Or it may be a spasmodic burst of opinion rather than a considered strand of opinion.’ Dealing with that, I think, is very tough. The other thing I think’s really interesting, when I look back on my time – and I say this to leaders a lot – is that as a result of the way the media works today, scandals and crises, that is just part of your life. So you’re living with a constant, as I say, barrage of noise and static around you.

JR: My esteemed colleague Steve Richards said there was no such thing as a Blairite in a column the other day, which I disagreed with. But I found it rather difficult to formulate a definition of what a Blairite was except somebody called Alex Doel sent me a message on Twitter to say that a Blairite is an individual who stubbornly refuses to make the Labour Party unelectable. I wondered what you thought of that definition.

TB: Yeah, I told you Twitter was good. No, I think it’s a lot more than that, actually. There is a modern, progressive political strain that is saying our essential values around social justice and the creation of a more just society where opportunity is given to people irrespective of their background or wealth – that remains our core objective, but the means of achieving it has got to change in a revolutionary way because the world around us has changed. So globalisation, technology, demography mean these things have got to be delivered in different ways. So the academy programme is a programme born out of the fact that bad schools do not deliver social justice. And if bad schools are delivering a bad education for the pupil, at some point you’ve got to understand whether this is a systemic change that’s necessary, and make it. That’s what it’s about. It’s about modern, progressive politics.

Now, I happen to think it’s the politics that makes you electable, but the reason for that is politicians sometimes talk about electability as if it’s just a matter of conning the public. Actually, it’s a matter of persuading the public and in my experience, usually, the public gets it right.

JOHN BOULTON (FORMER QUEEN MARY STUDENT): Jonathan Freedland wrote in the Guardian a couple of days ago that Gordon Brown should apologise for the mistakes that were made under his government for the sake of Ed Miliband and for the sake of your and his government’s legacy, do you agree?

TONY BLAIR: I think for the Labour Party to accept that, as it were, the [financial] crisis was created in Downing Street, it would be bizarre. It’s a crisis that’s occurred literally all over the Western world, all governments have faced enormous challenges as a result of the massive drop in growth. And one of the first things that you learn about government is that the issues to do with debt are hugely impacted by issues to do with growth. So if your growth falls, you’re in a situation where – and especially if it falls, plummets in the way that it did after the financial crisis in 2009 – whatever government is in power is going to have a major problem.

And, by the way, one thing I always reflect on is in my ten years in office, I don’t think I really was ever met with an opposition that was telling me to spend less.

MATT FORDE (MILE END GROUP MEMBER): I just wanted to ask, what hope is there of the Labour party having a leader one day that won’t be a formal special advisor, perhaps, in the next 10/15 years?

TB: I support Ed’s leadership and I support what he’s doing, but I think there is a general problem in politics, not just in our system but in Western democracy – I mean, it’s a far bigger topic this. But, I do think it’s really important.

I advise any young person who wants to go into politics today: go and spend some time out of politics. Go and work for a community organisation, a business, start your own business; do anything that isn’t politics for at least several years. And then, when you come back into politics, you will find you are so much better able to see the world and how it functions properly.

TOM ROBINSON (FORMER QUEEN MARY STUDENT): Mrs Thatcher once famously said, ‘Every Prime Minister needs a Willie.’ Do you think the reason why you didn’t refer to Cabinet government as much as you did is because you didn’t have one or you had too many?’

TB: Well, we had, let’s say, a few competing power centres in government, and that’s the way it is. John Prescott in many ways was the person who helped me a lot with the party, and that was important. Because you’ve got to manage your political system, and managing your colleagues is very tough, because politics is a very competitive business. Oonly so many positions; people want them. I was amazed at the number of people who wanted to be Foreign Secretary, and I was even more amazed at the number of people who thought they could be Foreign Secretary. But you have to say no.

I remember having this conversation with Alex Ferguson, discussing what you did with difficult people, and Alex’s view was, if they’re difficult, out the door. I said to him,‘Well, I understand that, but what would you do if once you’d put them out they still had the right to be in the dressing room?’ He said, ‘Well, no, that would be a problem,’ he said. So I think my problems in the end were perfectly natural, and the fact is, I survived ten years with it, which in today’s terms I think is quite a lot.

JR: Talking of your coalition with Gordon Brown, don’t you regret not building up someone else who could at least have fought a leadership election against Gordon Brown after you stepped down?

TONY BLAIR: Well, I’m not sure prime ministers can do that, really. He was obviously the person with huge stature and so on within the government and, to an extent, within the country. And I’m not sure it would have really been very sensible for me to try and engineer; someone else had to step forward. In the end, they didn’t.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments