The search for the £1.9bn Atlantic treasure lost at sea - which may not actually exist

For years, the UK has been fighting to claim the spoils from a huge shipwrecked cargo of platinum

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Early in 2012, a former swimming pool installer turned treasure hunter called Greg Brooks made global headlines when he announced the discovery of the SS Port Nicholson – a British freighter sunk off America in 1942, thought to be carrying £1.9bn of Russian platinum to pay for weaponry to help an increasingly desperate Stalin defeat Hitler.

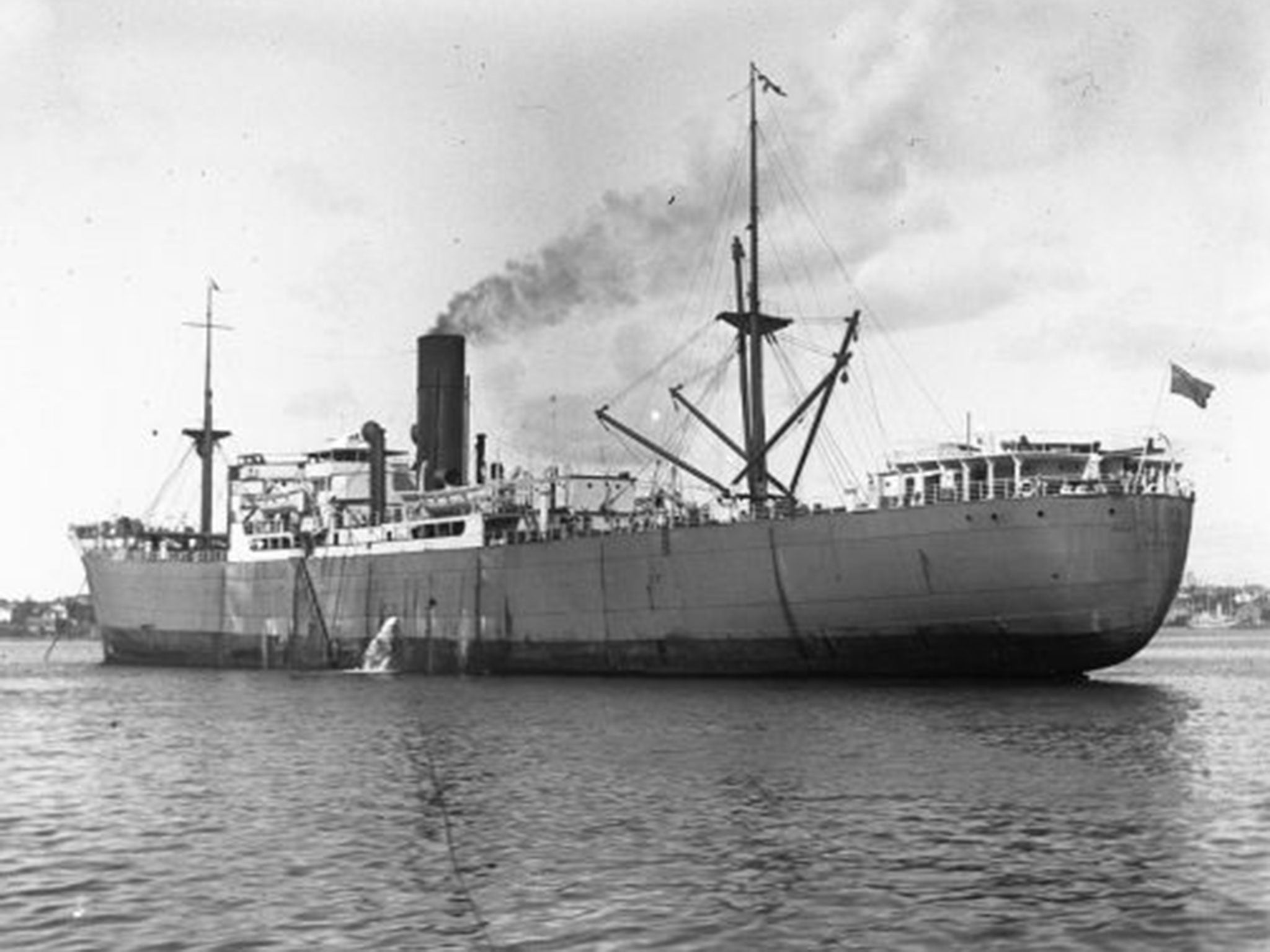

Even by the swashbuckling standards of hunts for unusual shipwrecks, it was a compelling tale. The smoke-belching British vessel had left the Arctic port of Murmansk in the summer 1942 secretly laden with 71 tons of precious metal, safeguarded by two Soviet special envoys, before it was holed by two torpedoes fired by a Nazi U-boat and sank in 700ft of water off the Massachusetts coast. The two Russians escorting the consignment survived the sinking but disappeared without trace.

Mr Brooks, a burly and moustachioed former amateur diver, said he had found documents, including a cargo list for the Port Nicholson, which, along with evidence from the seabed such as scattered wooden bullion boxes, proved he was within touching distance of the most valuable wreck in history.

The salvor said: “It’s there just waiting for us to recover it. It’s not an easy task, but we won’t stop until we get it.

“It is every kid’s dream to be treasure hunter and some adults dream of it too.”

Such an intoxicating cocktail of wartime intrigue and modern enrichment caused a ripple of excitement that crossed the Atlantic – all the way to the custodians of Britain’s lost ships in Whitehall.

The Department for Transport (DfT) asserted Britain’s ownership of the freighter and everything on board in the US courts on the basis that the Port Nicholson had been requisitioned by the state for war duties at the time of its loss.

The scene was set for a fresh Atlantic tussle between London, Moscow and American treasure hunters.

However, it turns out that Mr Brooks’ headline-grabbing claims were at least partially based on allegedly forged documentation, which has led many to conclude that the 71 tons of platinum worth $3bn never existed. In addition, federal investigators are looking into possible fraud committed against investors who poured millions into Mr Brooks’ company, Sub Sea Research.

The treasure hunter and his firm were recently stripped of their licence to salvage the ship by a US court, after it heard that repeated trips to the site of the sinking – some 50 miles off Cape Cod – had failed to secure a single bar of platinum despite costing $6m (£3.8m) of investors’ cash.

Judge George Singal, sitting on the case in the US District Court of Maine, said the evidence suggested that, rather than holding hundreds of bars of one of the most expensive substances on earth, all that was to be found on the Port Nicholson were “70-year-old truck tyres, fenders and miscellaneous other parts and military supplies”.

To add to the intrigue, The Independent has learned that the DfT has spent thousands of pounds on legal fees and on the work of civil servants to secure the seizure of the few artefacts that Mr Brooks and his team managed to bring to the surface during four years of exploration.

American court documents show that the US lawyers acting for the DfT last month secured an order from Judge Singal requiring the artefacts to be returned to Britain.

The department refused to disclose what those artefacts were. But anyone anticipating a trove of loot to be returned to HM Treasury’s depleted coffers will be disappointed. The US documents obtained by The Independent show that the booty consists of six largely worthless items, including bricks of bitumen, a dented fire extinguisher and a large block of rust thought to be fused axe heads. The sole noteworthy item is the smashed remains of the Port Nicholson’s compass.

The DfT defended its pursuit of a block of rust, for which it employed two law firms, by saying it had a duty to safeguard sovereign property.

In a statement, the department said: “We pursued this case in order to protect the Government’s long-term strategic interest in all of the World War I and World War II wrecks it owns.”

But despite being sued by his investors and forced to surrender what little he was able to retrieve from the Port Nicholson to London, Mr Brooks, based in Maine, remains defiant.

The former swimming pool contractor sank his savings into founding Sub Sea Research in 1984 and has pursued a succession of shipwreck projects in the past 30 years, attracting investors’ money for searches from Spanish galleons to wartime bullion vessels.

His detractors say none of these ventures has resulted in significant loot, despite promises of extravagant potential rewards. Following the discovery of the Port Nicholson, he once said: “We’ll be the biggest stimulus package Maine has ever seen. I’m going to make sure no kid in Maine ever goes hungry again.”

In a statement to The Independent, he revealed his anger at having to hand back his finds from the Port Nicholson to the British state after battling vicious currents and storms in the Atlantic to obtain them.

He said: “Aggrieved is a mild word for all this. After risking our lives and all the work we went through to get these items, not to speak of the cost, why should [the Department for Transport] get these?”

Saintly patience and super-human levels of determination are often cited as basic requirements for success in the ruthlessly competitive world of marine salvage. Mel Fisher, a former chicken farmer turned Florida salvor, spent 16 years searching for a Spanish galleon, Nuestra Senora de Atocha, before finding it in 1985. His reward was an 80 per cent share of the bullion on board – £250m.

In 2012, Mr Brooks thought he was on the brink of a pay-out that would dwarf even Mr Fisher’s success. He had in fact discovered the Port Nicholson wreck in 2008 but kept it under wraps by claiming he had found a ship called the “Blue Baron” thousands of miles south of Guyana.

In the meantime, the treasure hunter paid an American researcher, Edward Michaud, to seek extra proof of the platinum cargo by looking through records relating to the Port Nicholson, a refrigerated cargo ship built on Tyneside in 1918, which had a chequered history of groundings and fires.

What Mr Michaud found appeared to confirm that the 500ft-long coal-fired freighter was indeed on a secret mission to deliver Soviet payments under America’s Lend-Lease scheme to provide equipment to its allies, including Britain. After the U-boat attack it sank slowly, allowing time to rescue all but six of the 91 crew.

One of the two corroborating documents unearthed by the researcher, supposedly from a former US naval intelligence officer named Jack MacCann, was the passenger and cargo manifest carrying the word “bullion”.

But in a submission to the American court last December, Mr Brooks was forced into a disastrous admission. He explained that Mr Michaud had asked to meet him a few days earlier, and admitted: “During that meeting, [Mr Michaud] disclosed to me for the first time that he had fabricated the two documents in question. I was stunned and extremely dismayed. I asked him ‘what about Jack MacCann?’. He replied, ‘I made him up’.”

In reality, doubts had been raised about the likelihood of the Port Nicholson carrying vast amounts of platinum soon after Mr Brooks had made his announcement three years ago. Among the sceptics was the British Government, which said that as far as it was concerned the ship was carrying “mostly machinery and military stores” from Southampton to New Zealand.

Timothy Shusta, one of the lawyers representing the DfT, pointed out that between 1937 and 1941, annual global production of platinum had ranged between 14.5 tons and 16.9 tons. In order for the Port Nicholson to have been carrying the 71 tons claimed by Mr Brooks, the vessel would have been holding five years’ of the entire global supply of the precious metal.

After successive trips to the wreck site ended with reports from Sub Sea Research that recovery efforts had been variously thwarted by bad weather or inadequate equipment, some investors became disenchanted and sued Mr Brooks for the return of their funds.

The Office of Securities, a US financial watchdog, has said it is investigating Sub Sea Research following a complaint that investors may have been deliberately misled. Another group of investors has also said it wants to take over the Port Nicholson search.

But as yet no charges have been brought and Mr Brooks, though battered, remains unbowed. He insists his search was based on other documentation that predates any involvement of Mr Michaud, including a ledger of bullion shipwrecks, which it is claimed originates from the archives of the Bank of England.

The treasure hunter, who was forced to admit in court that his company “at present lacks the resources” to pursue the Port Nicholson project, questions why Britain has been so assiduous in its defence of its ownership of the freighter.

He said: “The UK has never litigated [over the ownership] of a freighter, except the Port Nicholson. Why? I 100 per cent believe there is something about the Port Nicholson. Why didn’t [the British Government] just let us waste our money to see what’s in her if they say there’s nothing?”

With his search vessel, the MV Sea Hunter, up for sale and the coffers empty, Mr Brooks’ search for the sunken billions would seem to be over.

But is he giving up?

He told The Independent: “I have put everything into this project, spent every penny I have, fought two governments, risked my life and my crews more than once, and so much more. Will I give up? No.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments